A23a, which calved from Antarctica's Filchner‑Ronne Ice Sheet in 1986, has degraded into streaks of blue melt ponds and white ice ramparts in recent satellite images, indicating it is breaking apart after nearly 40 years. Grounded for decades, the berg freed itself in 2020, spun in a gyre, then drifted toward South Georgia before fragmenting in May 2025. NASA Terra images from Dec. 26, 2025, and an ISS photo on Dec. 27, 2025, show the remnant reduced to about one‑third of its former size and surrounded by hundreds of smaller fragments.

Once the World's Largest, Iceberg A23a Has Turned Into a Stripy 'Blue Mush' as It Breaks Up After Nearly 40 Years

The iceberg known as A23a — once the planet's largest — has degraded into a patchwork of vivid blue melt ponds and white ice ramparts in recent satellite images, a sign that the colossal berg is finally breaking apart after almost four decades at sea.

From Grounded Giant to Drifting Remnant

A23a calved from Antarctica's Filchner‑Ronne Ice Sheet in the Southern Hemisphere summer of 1986. Unusually, the iceberg became grounded soon after calving when its submerged keel caught on the seafloor. That grounding kept the berg close to its parent ice shelf and helped preserve much of its mass for decades.

In 2020 A23a finally freed itself and began drifting away from Antarctica. It spent months spinning inside a large ocean gyre before escaping in December 2024 and moving north toward the sub‑Antarctic island of South Georgia. Scientists feared the iceberg might ground again and damage local ecosystems, particularly penguin colonies, but the worst‑case scenario was averted when the berg began fragmenting in May 2025.

What the Recent Images Reveal

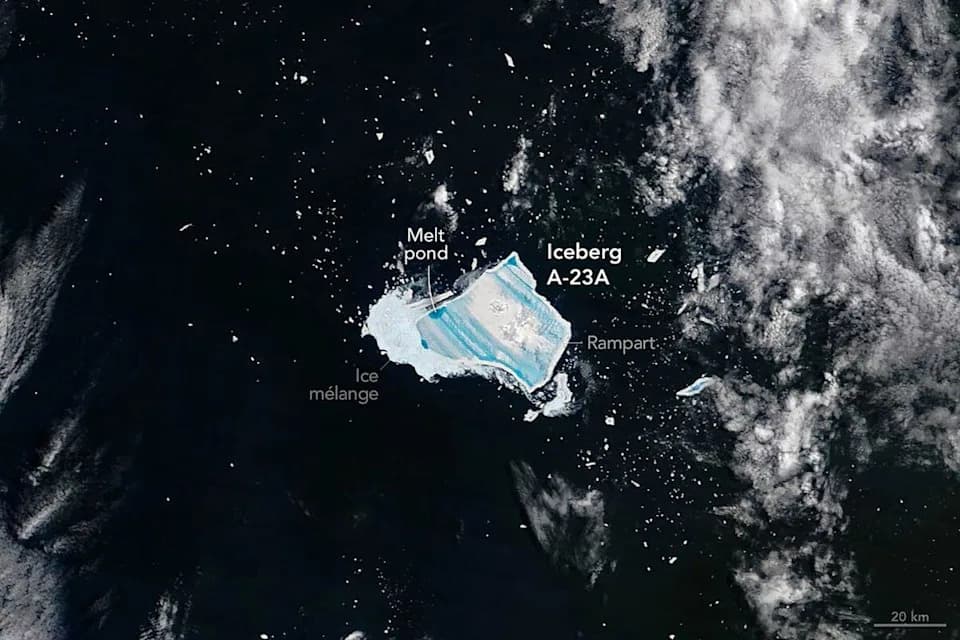

New imagery from NASA's Terra satellite taken on Dec. 26, 2025, shows the iceberg reduced to roughly one‑third of its original area. The remnant is streaked with bright blue melt ponds surrounded by thicker white ice "ramparts." Hundreds of smaller bergs and bits of ice have calved from its edges, and a gray fringe of ice mélange — slushy, mixed sea ice and berg fragments — sits nearby.

Ted Scambos, a climate scientist at the University of Colorado Boulder, said the blue streaks are melt ponds that form where surface ice has lost structural integrity. "The weight of water sitting in surface cracks forces them open and elongates the ponds," he said in a NASA statement.

Researchers note that the surface cracks align with grooves on the iceberg's underside, carved when the ice moved over bedrock as part of the Filchner‑Ronne Ice Sheet. "It's impressive that these striations still show up after so much time has passed," Walter Meier of the National Snow & Ice Data Center (NSIDC) said, a point echoed by retired glaciologist Chris Shuman.

An astronaut aboard the International Space Station captured a follow‑up photo on Dec. 27, 2025, showing the high‑contrast striping already beginning to fade into a more uniform melt pool — a sign the berg's surface is continuing to break down.

Why It Matters

Though A23a repeatedly held the informal title of the world's largest iceberg during its long life, it lost that status following fragmentation in 2025. According to NSIDC, the current largest known iceberg is D15A at about 1,200 square miles (3,100 square kilometers). The breakup of A23a illustrates how prolonged grounding, long‑distance drifting, ocean currents and warming waters combine to fracture and melt even the largest ice masses.

At present it remains unclear exactly how much of A23a is left or whether the remnant has already disintegrated into many smaller fragments and sea ice. Scientists continue to monitor the region with satellites and ship‑based observations.

Help us improve.