Seabed cores from the Amundsen Sea reveal that during the Pliocene (about 4.7–3.3 million years ago) the West Antarctic Ice Sheet repeatedly collapsed, allowing open ocean to penetrate interior basins. A sandstone pebble traced ~800 miles (1,300 km) inland and chemical fingerprints tied mud layers to the Ellsworth Mountains, showing long-distance iceberg transport. Those rapid deglaciations triggered uplift, earthquakes, increased volcanism, massive landslides and tsunamis — a pattern the authors call "catastrophic geology" — and suggest similar abrupt changes could recur if the ice sheet collapses again.

Ancient West Antarctic Melts Foreshadow Fast, ‘Catastrophic’ Geological Change

Antarctica often appears as a single, frozen continent, but beneath that white expanse the West Antarctic Ice Sheet behaves more like a moving thumb — thinning, flowing and retreating as Earth's oceans and atmosphere warm. New analyses of seabed cores show that when West Antarctica melted in the past, onshore geology responded rapidly and violently. Those past events offer a stark preview of what deglaciation could trigger in the near future.

New Evidence From the Seafloor

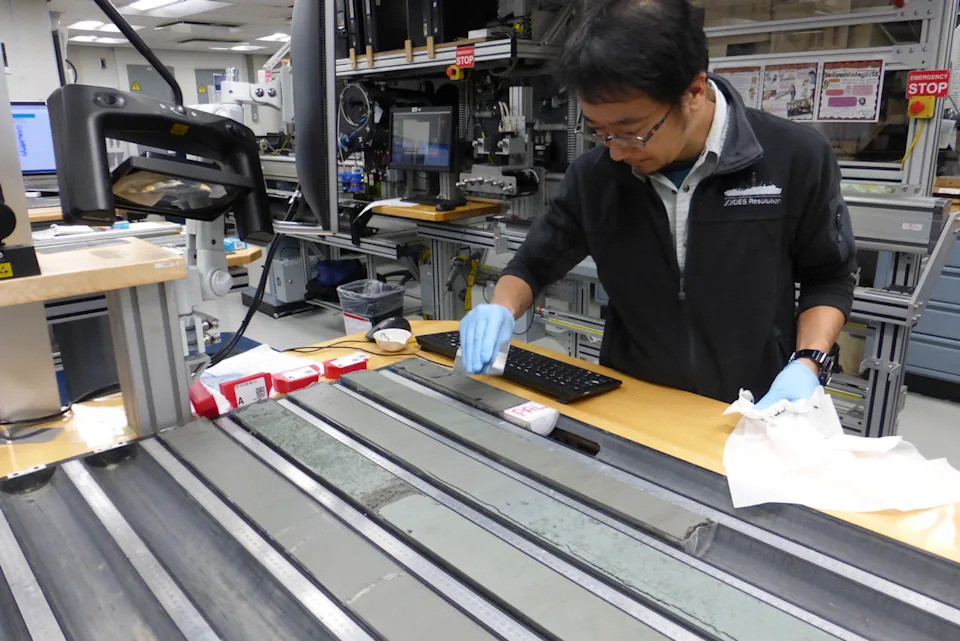

In early 2019, scientists aboard the drillship JOIDES Resolution as part of International Ocean Discovery Program Expedition 379 extended a drill string nearly 13,000 feet (3,962 meters) to the ship and bored 2,605 feet (794 meters) into the seabed offshore the Amundsen Sea. The expedition recovered long cylindrical cores recording sediment deposition from roughly 6 million years ago to the present, with especially informative layers from the Pliocene Epoch (5.3–2.6 million years ago), when global climates were relatively warm.

Surprising Pebbles and Chemical Fingerprints

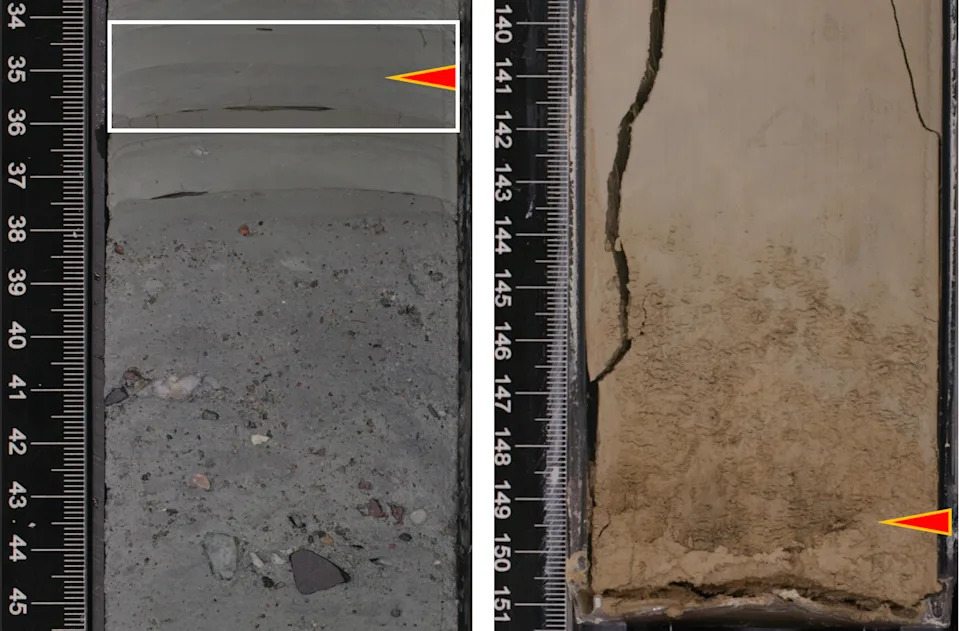

Among the finds was a rare sandstone pebble in a disturbed core interval. Laboratory analysis showed the pebble originated in interior Antarctic mountains roughly 800 miles (1,300 km) from the drill site, indicating icebergs had transported rock from deep inland out to the Pacific-facing Amundsen Sea. Additional geochemical and paleontological analyses — including elemental ratios of strontium, neodymium and lead, and magnetic signatures — linked thin mud horizons in the core to outcrops in the Ellsworth Mountains about 870 miles (1,400 km) away.

Repeated Rapid Collapses During the Pliocene

Keiji Horikawa and colleagues identified as many as five mud layers deposited between about 4.7 and 3.3 million years ago. Each of these horizons represents deposition immediately after a deglaciation that released iceberg-rafted debris to the seafloor. The layers indicate repeated cycles in which the ice sheet collapsed, open seaways formed across interior basins, and the ice later re-advanced — with each cycle occurring over thousands to tens of thousands of years.

Modeling and Coastal Consequences

Numerical models combining the geochemical timeline with ice dynamics (developed by Ruthie Halberstadt and team) show how ocean inundation could have converted thick interior ice into an archipelago of rugged, ice-capped islands. Model outputs indicate rapid, large-scale iceberg production and a dramatic retreat of the ice margin toward the Ellsworth Mountains, leaving the Amundsen Sea choked with icebergs that shed continental debris as they melted.

‘Catastrophic Geology’: Uplift, Quakes, Volcanoes, Landslides and Tsunamis

Global geological records show that unloading large ice masses causes the land to rebound. In West Antarctica, where the mantle is relatively warm, that rebound can be especially rapid and is likely to trigger seismic activity. Release of lithospheric pressure also tends to increase volcanic activity — consistent with a volcanic-ash layer the team dated to about 3 million years ago. Rapid uplift and weakened, fractured bedrock led to massive subaerial and submarine collapses, producing huge landslides and tsunamis. These abrupt, widespread processes have been termed "catastrophic geology."

Biological Responses And Broader Implications

Deglaciation would not only reshape the land and seafloor but also provoke fast ecological changes: algal blooms around drifting icebergs, rapid colonization of newly exposed ground by mosses and coastal vegetation, and expanded pathways for marine species into newly opened seaways. Taken together, the geological and biological responses would be felt locally as dramatic, even apocalyptic events, and would have consequences that ripple globally.

What This Means For The Future

The sedimentary and geochemical evidence demonstrates that West Antarctica's ice sheet does not simply retreat once and stabilize: it has swung repeatedly between thick ice cover and much more open, ocean-dominated states. Each prior disappearance of the ice sheet was accompanied by rapid geological upheaval. Given current warming trends, the same chain of events — rapid ice loss, uplift, seismicity, volcanism, landslides and tsunamis — could recur. While the timing and extent depend on many variables, the geologic record warns that future changes could be fast and severe on human timescales.

Authors and Funding: This research was led by Christine Siddoway (Colorado College), Anna Ruth (Ruthie) Halberstadt (University of Texas at Austin) and Keiji Horikawa (University of Toyama). Funding included the U.S. Science Support Program for IODP and the U.S. National Science Foundation (grants 1939146 and 1917176) and JSPS KAKENHI Grants (JP21H04924 and JP25H01181).