Cosmic rays — high-energy protons, helium nuclei, heavy ions and electrons from the Sun and distant stars — pose a major hazard for crewed missions beyond Earth's magnetic field. Current accelerator-based simulations in the US and Germany are informative but often compress exposure into single doses and do not reproduce the mixed particle fields of deep space. Researchers propose multi-beam accelerator facilities and are exploring biological countermeasures (antioxidants, hibernation-like states, stress-response activation) to supplement shielding. A combined strategy and increased investment are needed to protect astronauts on missions to the Moon, Mars and beyond.

Before We Go to Mars: Fixing the Invisible Threat of Cosmic Rays

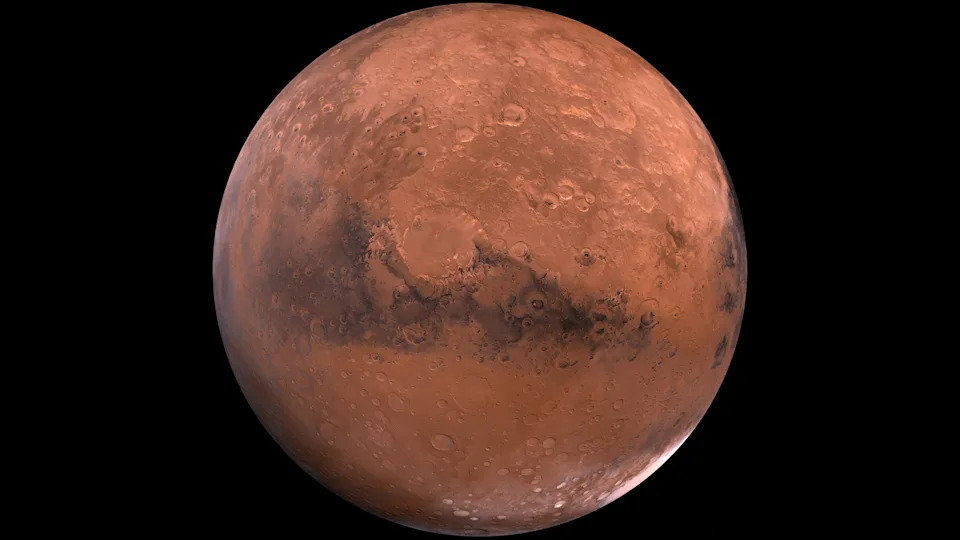

The first human steps on the Moon were among humanity's greatest achievements. As NASA prepares Artemis II and Artemis III and planners aim for crewed missions to Mars in the 2030s, an invisible hazard threatens long-duration deep-space travel: cosmic rays.

What Are Cosmic Rays?

Cosmic rays are high-energy charged particles — mostly protons, helium nuclei, heavier ions and electrons — that come from the Sun (solar particle events) and distant exploding stars (galactic cosmic rays). They travel at very high speeds and carry enough energy to ionize atoms, knock electrons from molecules and disrupt the structure of materials and living cells.

Why They Matter For Astronauts

On Earth, our magnetic field and dense atmosphere block most cosmic radiation. In deep space, however, crews outside Earth’s magnetosphere face continual exposure. At the cellular level, cosmic rays can break DNA strands, damage proteins and other structures, and raise the long-term risk of diseases such as cancer. They can also impair cognitive function and degrade spacecraft electronics and materials.

Limits Of Current Ground Simulations

To study radiation effects on biology, researchers send tissues, organoids and animals to space when possible. More commonly, they use particle accelerators on Earth. Facilities in the United States and Germany simulate different components of cosmic rays, and an international accelerator complex under construction in Germany will reach higher energies than previously tested.

But current ground experiments have important shortcomings. Many deliver an entire mission-equivalent dose in a single session — more like a tsunami than the steady, mixed bombardment of deep space. Experiments also typically expose subjects to one particle type at a time, whereas real deep-space radiation is a complex, simultaneous mix of particle species and energies.

To address this, researchers have proposed a multi-branch accelerator able to fire several tuneable beams at once, recreating realistic mixed radiation fields in the laboratory. That proposal could improve the relevance of Earth-based tests but is not yet built.

Why Shielding Alone Is Not Enough

Physical shielding — materials rich in hydrogen such as polyethylene and water-based hydrogels — can slow charged particles and are already used or proposed for spacecraft. However, very energetic galactic cosmic rays can penetrate conventional shields and generate secondary radiation inside the shielding material itself, which can increase biological dose rather than reduce it. Relying solely on thicker passive shielding is therefore unlikely to be sufficient for long-duration missions beyond low Earth orbit.

Biological Countermeasures: Promising But Early

Because physical shields have limits, scientists are exploring biological strategies to reduce harm. These include:

- Antioxidants: Molecules that neutralize damaging reactive chemicals produced when radiation strikes tissue. In animal studies, the synthetic antioxidant CDDO-EA reduced cognitive deficits caused by simulated cosmic radiation: mice given CDDO-EA performed better on learning tasks than exposed controls.

- Hibernation-Like States: Hibernating animals show increased radioresistance while dormant. Researchers can induce hibernation-like physiology in non-hibernators and see greater radioresistance in some cases. The precise protective mechanisms remain under investigation, but they may inform ways to preserve biological materials during transit.

- Extremophile Insights: Organisms such as tardigrades tolerate extreme radiation, especially when desiccated. While we cannot dehydrate astronauts, understanding the molecular strategies these organisms use could guide preservation techniques for microbes, seeds, food supplies or biological cargo that might be sheltered in a dormant, protected state.

- Stress-Response Activation: Natural stressors on Earth (caloric restriction, heat, etc.) trigger cellular defense pathways that protect DNA and proteins. A recent preprint suggests that specific diets or drugs could stimulate these endogenous defenses and add protection for space travelers.

What’s Needed Next

Solving space radiation risk will require a portfolio approach: better ground-based simulations (including multi-beam accelerators), more biological experiments in space, improved materials and spacecraft design, and research into biological countermeasures. These efforts will be costly and technically demanding, and at our current pace fully robust solutions for routine deep-space crewed travel are likely decades away.

Conclusion: Physical shields remain necessary but insufficient. Combining improved experimental platforms, innovative shielding strategies and biological protections — coupled with greater funding and international collaboration — is the most realistic path toward enabling safe, long-duration human missions beyond Earth’s protective bubble.