A Syracuse University study links the unusual remnant PA 30 (discovered in 2013) to the naked-eye supernova recorded in 1181, SN 1181. The authors propose SN 1181 was a partial Type Iax explosion that left a surviving "zombie star." Strong, heavy-element winds from that remnant could have preserved the remnant’s radial filaments, producing PA 30’s long-lived "firework" appearance. The work implies many supernovae may briefly pass through a similar phase that usually goes unobserved.

Frozen Fireworks: How a Partial Supernova Explains PA 30 and the 1181 "Guest Star"

A new paper from Syracuse University researchers proposes a striking solution to a centuries-old astronomical mystery: the unusual remnant PA 30, discovered in 2013, and a bright "guest star" recorded by Chinese and Japanese observers in 1181 may be two pieces of the same puzzle.

The Historical Clue

Contemporary East Asian records describe a dramatic naked-eye object appearing in early August 1181 that remained fixed in the sky for 185 days. Because it was bright, long-lived, and stationary relative to the stars, the event has long been interpreted as a supernova within the Milky Way—now designated SN 1181.

The Modern Discovery

Independently discovered in 2013, the object PA 30 has a striking "koosh-ball" or "firework" morphology: a dense central source surrounded by numerous radial filaments. In 2021 multiple teams connected PA 30 to SN 1181. Observations reveal a surviving compact object at PA 30’s center, consistent with the so-called "zombie star" expected after a failed or partial supernova.

A Partial Explosion Explains the Shape

PA 30’s filamentary exterior is unusual for standard Type Iax remnants. The Syracuse paper argues that SN 1181 was a partial (abortive) Type Iax supernova—an explosion that began but did not complete—leaving a surviving remnant. That surviving star drove unusually strong winds enriched in heavy elements. Those winds had enough pressure and momentum to keep the early filaments coherent and moving outward, effectively "freezing" the firework-like structure for centuries.

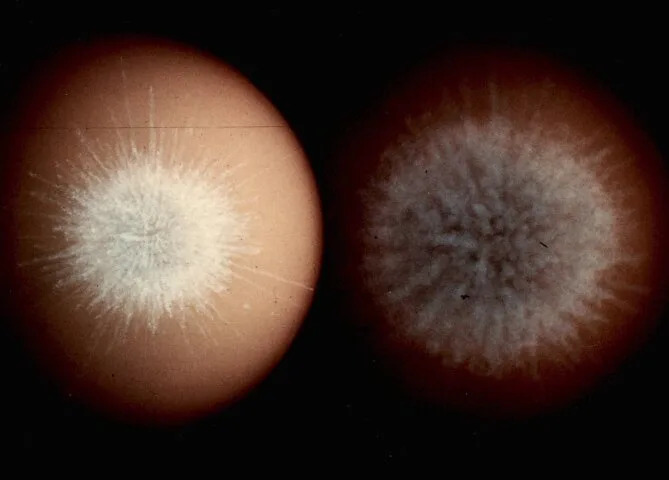

Laboratory Analogy: The Kingfish Test

To illustrate how a brief, highly ordered filamentary phase can appear and then quickly dissolve, the authors present freeze-frame images from the mid-20th-century Kingfish nuclear test. In the test, the explosion’s first tens of milliseconds show an orderly, radial pattern resembling PA 30; a few hundred milliseconds later the structure collapses into turbulence. The paper uses this analogy to argue that most supernovae likely pass briefly through a similar firework phase—but in typical cases the phase is too short to be observed unless preserved by a surviving remnant’s winds.

Implications

This scenario explains PA 30’s long-lived morphology without invoking exotic physics: a partial explosion produced the filaments, and a surviving "zombie star" with strong, metal-rich winds preserved them. If correct, the result suggests many supernovae may briefly display similar transient filamentary structure, but it usually vanishes within fractions of a second to minutes unless special conditions preserve it.

Takeaway: PA 30 and the 1181 guest star may be the same event—a rare example of a partial supernova whose early filamentary appearance was preserved by winds from a surviving star.

Help us improve.