Researchers at Syracuse University propose a unified explanation for a puzzling modern discovery and a medieval sky event: the bizarre remnant called PA 30 (discovered in 2013) and a bright “guest star” recorded by Chinese and Japanese observers in AD 1181.

The Mystery

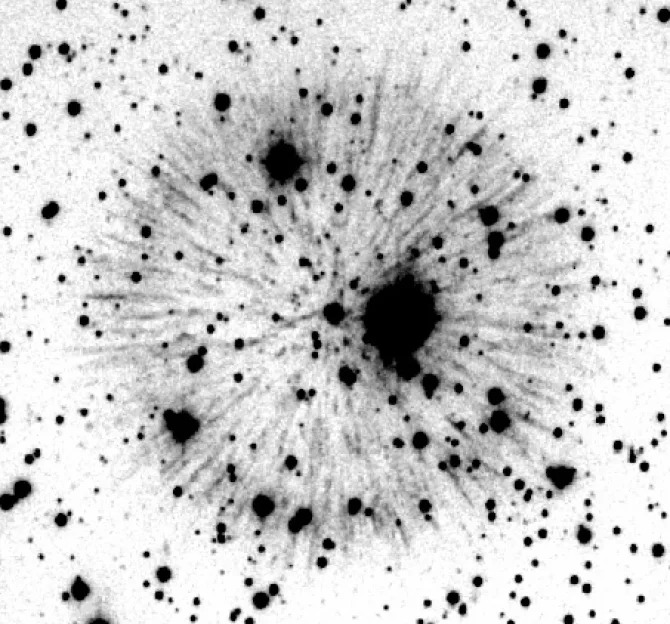

Medieval chronicles report a naked-eye object visible for roughly 185 days in early August 1181. Its brightness, long visibility, and fixed position on the sky are consistent with a supernova inside the Milky Way. Independently in 2013 astronomers found PA 30, a stellar remnant with a striking koosh-ball or "firework" morphology — a central object surrounded by long, radially aligned filaments.

What the New Paper Proposes

The authors argue that PA 30 is the remnant of SN 1181 and that the explosion was partial rather than a complete disruption. In this scenario the blast stalled after an initial explosive phase, leaving behind a surviving, energetic "zombie star." That survivor drove strong, heavy-element winds that swept up and preserved the early radially directed ejecta, maintaining the filamentary "firework" structure for centuries.

Evidence and Analogy

PA 30 has been linked to a Type Iax supernova — a rare subtype of Type Ia events that can leave a bound remnant. While classical Type Iax models do not naturally produce PA 30's long radial filaments, the partial-explosion-plus-strong-wind picture can: the winds are heavy-element rich and energetic enough to keep the initial filaments coherent and moving outward for a long time.

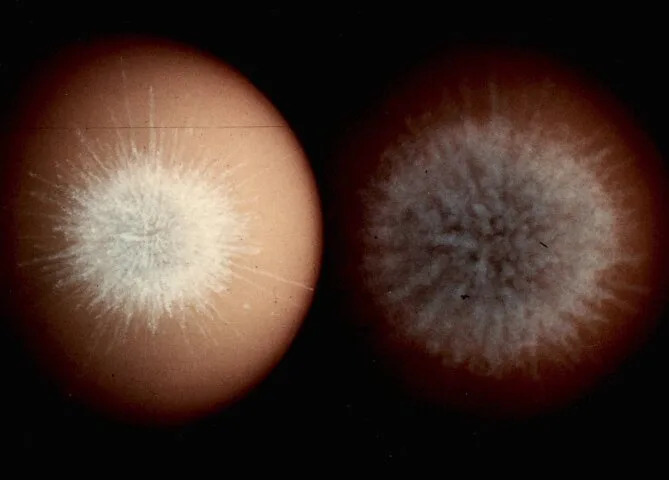

Kingfish nuclear explosion freeze

To illustrate how a brief early stage can look very ordered and then rapidly devolve, the paper compares freeze-frame imagery from the Kingfish nuclear test. In the first tens of milliseconds the detonation resembles PA 30's firework pattern, but within ~200 ms the pattern breaks into a chaotic, structureless cloud. The authors suggest that if a surviving star supplies sustained winds, that early firework phase can be frozen and extended to astronomical timescales.

Implications

If this interpretation is correct, many supernovae might pass through a similar short-lived "fireworks" stage right after explosion — a stage that is normally too brief to detect. PA 30 would be an unusually lucky case where a partially failed explosion and a persistent survivor combined to preserve and reveal that fleeting phase.

Credits: PA 30 image credit: Walter Scott Houston. Paper and Kingfish frames: Syracuse University (Coughlin et al.).