JWST spectra of galaxy GS 3073, 12 billion light-years away, reveal a high nitrogen-to-oxygen ratio consistent with nucleosynthesis in extremely massive "monster" stars (1,000–10,000 solar masses). Simulations show helium burning produces carbon that mixes into hydrogen-burning shells and generates nitrogen, which is then expelled into the galaxy. The models indicate these giants can collapse directly into supermassive black holes without exploding as supernovae, helping explain the rapid appearance of massive black holes after the Big Bang.

JWST Detects Chemical Traces of 'Monster' Stars That Seeded Early Supermassive Black Holes

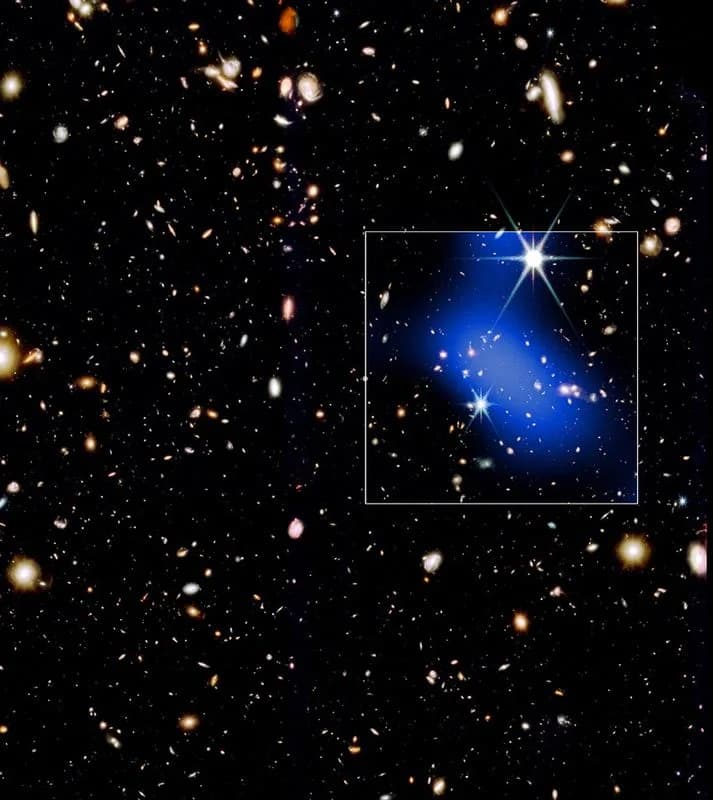

Astronomers using the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) have found the first direct chemical evidence that enormous "monster" stars — roughly 1,000 to 10,000 times the mass of the Sun — existed in the universe's infancy and likely collapsed to form supermassive black holes.

The team studied light from GS 3073, a galaxy about 12 billion light-years away that hosts a central black hole. Spectroscopy revealed an unusually high nitrogen-to-oxygen ratio — a chemical fingerprint the researchers say is best explained by nucleosynthesis inside supermassive stars early in cosmic history.

“These cosmic giants would have burned brilliantly for a brief time before collapsing into massive black holes, leaving behind the chemical signatures we can detect billions of years later,” said co-author Daniel Whalen, a cosmologist at the University of Portsmouth in the U.K. “A bit like dinosaurs on Earth — they were enormous and primitive.”

How the Chemical Fingerprint Forms

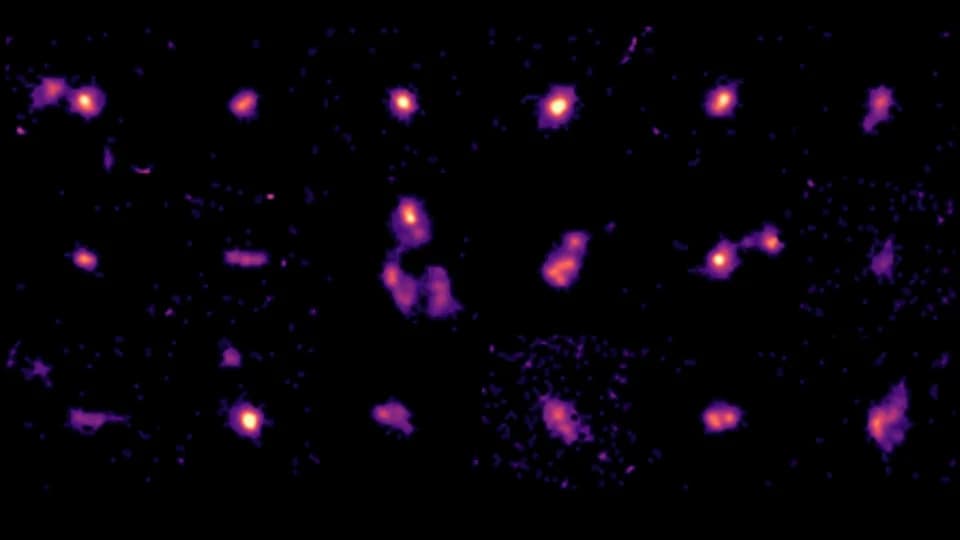

To test their interpretation, the researchers ran detailed stellar models and hydrodynamic simulations of supermassive-star evolution and collapse. In the models, helium burning in the core produces carbon. That carbon then mixes outward into a surrounding hydrogen-burning shell, where carbon and hydrogen reactions generate nitrogen. Convection spreads nitrogen-rich material through the star, and some of that processed gas is eventually expelled into the host galaxy, leaving the distinctive high N/O ratio seen by JWST.

Direct Collapse Into Black Holes

The simulations also show a dramatic final act: rather than exploding as supernovae, these very massive stars can skip the explosion phase and collapse directly into supermassive black holes. This rapid "all at once" collapse helps explain how supermassive black holes could already exist less than a billion years after the Big Bang.

Published in the Astrophysical Journal Letters (ApJL), the work connects JWST observations with theoretical predictions and offers a plausible route for the early formation of the massive black holes astronomers have observed in the young universe.

Why This Matters

Detecting chemical traces from the first generations of very massive stars opens a new observational window on the so-called "Cosmic Dark Ages" — the epoch when the first stars forged the elements that later built galaxies, planets, and life. These findings help resolve a two-decade mystery about how supermassive black holes grew so massive so quickly.

Help us improve.