Researchers with NANOGrav and Yale have developed a targeted method to locate likely merging supermassive black holes by combining pulsar-timing data with quasar brightness variability. Studying 114 active galactic nuclei, they ranked candidate sources and highlighted two leading galaxies—SDSS J1536+0411 ("Rohan") and SDSS J0729+4008 ("Gondor"). Rather than announcing a definitive detection, the study provides the first practical framework for identifying continuous, low-frequency gravitational-wave sources and linking them to visible galaxies.

Astronomers Narrow the Search for Merging Supermassive Black Holes Using Pulsar Timing and Quasar Light

Somewhere far across the universe, pairs of supermassive black holes can orbit each other so slowly that their motion is effectively invisible to telescopes. Each black hole can outweigh the Sun by millions or billions of times, and their slow inspiral toward merger can take centuries or longer.

A new study from researchers working with the North American Nanohertz Observatory for Gravitational Waves (NANOGrav), including physicists at Yale University, describes a practical way to pinpoint where these titanic binaries are most likely to reside. By combining tiny spacetime distortions measured with pulsar timing and targeted observations of unusually bright galactic centers, the team has produced the first workable framework for locating continuous gravitational-wave sources across the sky.

How the Method Works

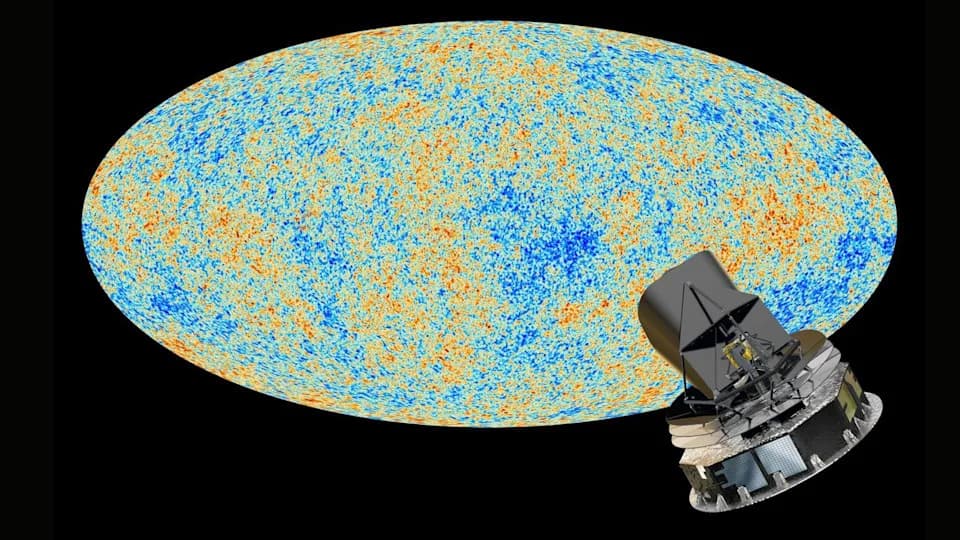

NANOGrav does not build a traditional detector. Instead it uses pulsars—rapidly spinning neutron stars that emit radio pulses at extraordinarily regular intervals—as a galaxy-scale array of natural clocks. Slow, nanohertz-frequency gravitational waves from supermassive black hole binaries would slightly advance or delay those pulses as spacetime between Earth and a pulsar warps.

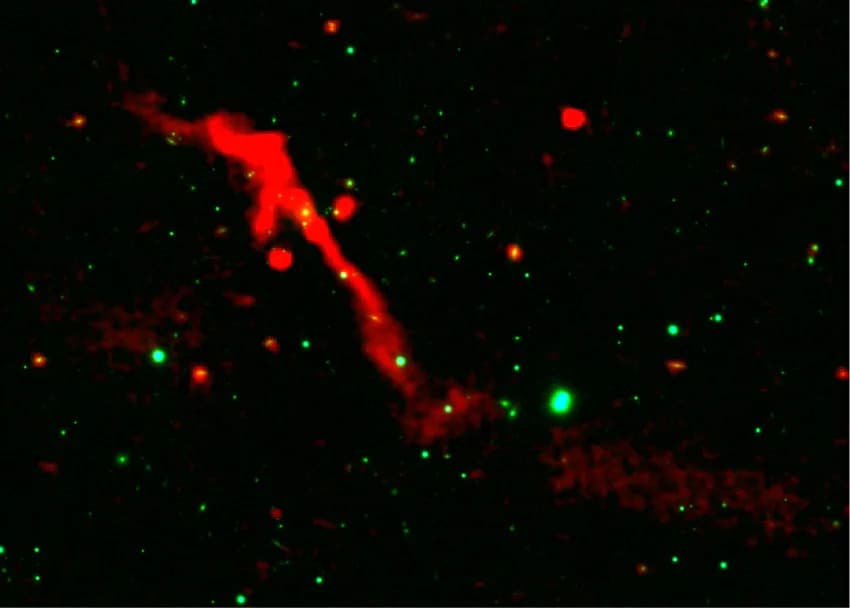

In 2023, pulsar-timing results provided strong evidence for a faint, all-sky gravitational-wave background produced collectively by many distant supermassive black hole pairs. That discovery, however, could not identify individual sources. The new study moves beyond a blind all-sky search by focusing on places where binaries are statistically more likely: active galactic nuclei (AGN) hosting quasars, which are bright because of matter accreting onto central black holes.

Targeted Search of Active Galactic Nuclei

The team examined 114 AGN, merging pulsar timing datasets with measurements of quasar brightness variability over time. This hybrid approach let researchers evaluate whether any given galaxy could plausibly produce a steady, continuous gravitational-wave signal strong enough to influence pulsar timings observed from Earth. Rather than claiming a definitive detection, the study ranked candidates by how well they matched the expected signature.

"Our finding provides the scientific community with the first concrete benchmarks for developing and testing detection protocols for individual, continuous gravitational wave sources," said Chiara Mingarelli, assistant professor of physics at Yale and a co-author of the study.

Two galaxies rose to the top of the list: SDSS J1536+0411 and SDSS J0729+4008, informally nicknamed "Rohan" and "Gondor." The playful names reflect both contributor recognition—Rohan Shivakumar, the Yale student who first analyzed one candidate—and the team's excitement: "the beacons were lit," in Mingarelli's words.

Why This Matters

Most immediately, the work provides a practical detection framework rather than a finished catalog of confirmed mergers. Even a few confirmed continuous sources would serve as fixed reference points, helping astronomers interpret the gravitational-wave background, tie it to specific galaxies, and study how often galaxies and their central black holes merge. Over longer timescales, the method could inform how supermassive black holes grow and test whether gravity behaves exactly as current theories predict on the largest scales.

By linking invisible spacetime ripples to visible cosmic landmarks, this targeted strategy brings gravitational-wave astronomy closer to traditional electromagnetic observations and opens a new avenue for multimessenger studies of galaxy evolution.

Publication: The study is published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

Help us improve.