Fossil evidence from the Dry Mesa Dinosaur Quarry indicates juvenile sauropods were abundant and likely unguarded, making them a major food source for Jurassic predators. A reconstructed food web shows sauropods had more trophic links than armored ornithischians, explaining why predators like Allosaurus could rely on easy juvenile prey. As sauropod numbers declined later, theropods such as T. rex evolved greater size, vision and bite force to tackle larger, better-defended animals.

Jurassic 'Fast Food': How Baby Sauropods Fed Predators and Shaped Dinosaur Evolution

New analysis of fossils from Colorado's Dry Mesa Dinosaur Quarry suggests juvenile sauropods — the long-necked giants of the Jurassic — were often abundant, unguarded and an easy meal for carnivores. The study reconstructs a detailed food web showing how these vulnerable youngsters may have sustained predator populations and influenced the evolution of later, larger theropods.

Sauropods, Youth, and Predation

Sauropods are among the most iconic dinosaurs: massive bodies with extremely long necks and tails. That size would have deterred many attackers as adults, but maturation took years and many individuals died young. The researchers propose that because sauropod hatchlings and juveniles were numerous and probably received little parental care, they became a plentiful, low-risk food source for predators such as Allosaurus and Torvosaurus.

"Size alone would make it difficult for sauropods to look after their eggs without destroying them, and evidence suggests that, much like baby turtles today, young sauropods were not looked after by their parents."

What the Food-Web Reconstruction Shows

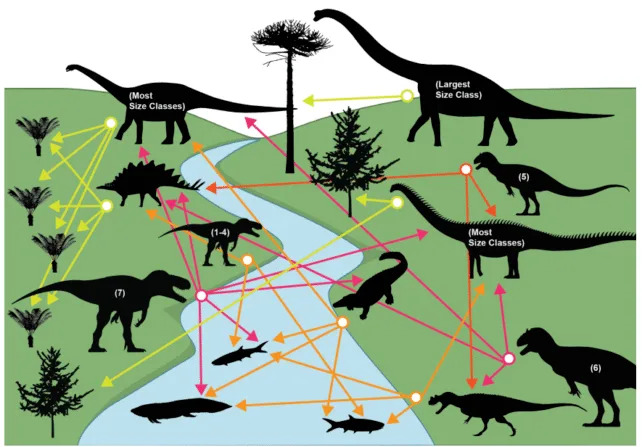

The team used published dietary and ecological data to map trophic links among plants, herbivores and predators in the Dry Mesa community (about 150 million years old). Their network analysis found that sauropods featured in many more feeding links than ornithischian herbivores. One likely reason: ornithischians often carried active defences — for example, the spiked tail of a Stegosaurus or the armor of Gargoyleosaurus — making them riskier targets than exposed sauropod juveniles.

Because juvenile sauropods were such an abundant, easy resource, top predators of the Late Jurassic may not have needed the extreme size, vision or bite power later evolved by animals like Tyrannosaurus rex. When sauropod numbers declined in later periods, theropods faced a different prey landscape and evolved adaptations suitable for tackling larger, better-defended prey such as Triceratops.

"The apex predators of the Late Jurassic, such as the Allosaurus or the Torvosaurus, may have had an easier time acquiring food compared to the T. rex millions of years later."

The findings appear in the New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin, and illuminate how prey availability can shape predator morphology and behavior across deep time.

Help us improve.