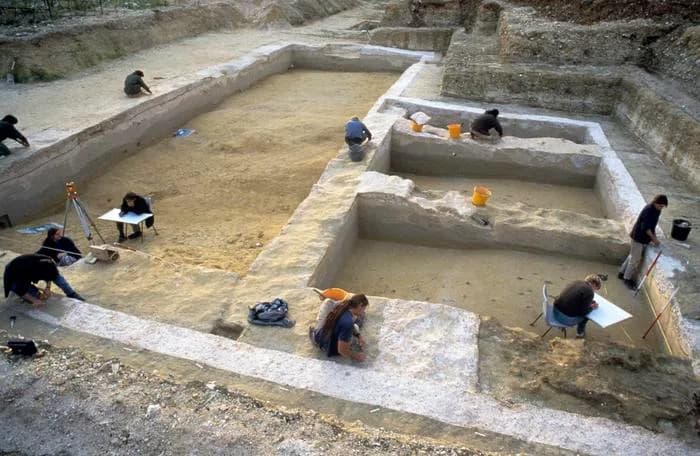

Researchers at Curtin University analyzed more than 500 zircon crystals from rivers and sediments around Salisbury Plain and found no mineral signature indicating glacial transport. Published in Communications Earth and Environment, the study shows local detrital zircon ages match southern British (London Basin) sources, implying sediment recycling rather than ice movement. These results make human transport of Stonehenge’s bluestones far more plausible, though the exact methods used by prehistoric people remain unknown.

New Study Strengthens Case That Humans — Not Glaciers — Moved Stonehenge’s Bluestones

New geological evidence strengthens the argument that people, rather than ice sheets, transported Stonehenge’s iconic bluestones to Salisbury Plain roughly 5,000 years ago. A team from Curtin University used advanced mineral fingerprinting to examine mineral grains from river sands and surrounding sediments, building a clearer picture of regional sediment sources and transport history.

What the researchers did

The team analyzed more than 500 zircon crystals — one of Earth’s most durable minerals — recovered from rivers and sediments near Stonehenge. Zircon crystals preserve geochemical and age information that act like tiny geological time capsules, allowing scientists to trace where sediment originated and how it moved across the landscape over millions of years.

Key findings

Their geochemical and age data show no mineral signature consistent with long-distance glacial transport from distant sources such as Scotland or parts of Wales. Instead, the detrital zircon ages around Salisbury Plain match those of southern British rocks tied to the London Basin, indicating local sediment recycling rather than glaciogenic supply.

“If glaciers had carried rocks all the way from Scotland or Wales to Stonehenge, they would have left a clear mineral signature on the Salisbury Plain,” said Anthony Clark, lead author and a member of Curtin’s Timescales of Mineral Systems Group. “Those rocks would have eroded over time, releasing tiny grains that we could date to understand their ages and where they came from.”

The team searched river sands for the expected glacier-derived grains and found none, a result the authors say makes direct glacial transport of the bluestones unlikely. As the study states, the evidence supports the conclusion that Salisbury Plain remained unglaciated during the Pleistocene, limiting the plausibility of ice carrying megaliths directly to the site.

“By analyzing minerals smaller than a grain of sand, we have been able to test theories that have persisted for more than a century,” said co-author Chris Kirkland.

What this means — and what remains unknown

The findings tip the balance toward human agency: it is now more plausible that people transported the bluestones to Stonehenge. However, because the study focused on mineral grains rather than archaeological transport evidence, it cannot resolve how ancient people accomplished the feat. Hypotheses include moving the stones overland on rollers or sledges or transporting them partially by boat, but the exact methods remain unresolved.

The paper, published in Communications Earth and Environment, adds an important geological constraint to long-standing debates about Stonehenge’s construction and will inform future archaeological and experimental research into how prehistoric communities moved enormous stones across challenging terrain.

Help us improve.