Summary: Decades of PFAS use in northwest Georgia’s carpet industry contaminated wastewater, rivers, soil and the blood of local residents. Internal company records and academic studies — including University of Georgia tests showing some of the highest PFAS levels in surface water — document persistent pollution that regulators and utilities struggled to control. Communities and municipalities have pursued lawsuits and remediation, but cleanup, health monitoring and federal rules remain incomplete.

Contaminated Carpet Country: The PFAS Legacy of Northwest Georgia’s Carpet Industry

DALTON, Ga. — When Bob Shaw, the CEO who turned a family firm into global carpet giant Shaw Industries, confronted 3M executives in 2000 and threw down a Scotchgard‑treated carpet sample, he crystallized a conflict that would ripple across northwest Georgia for decades: how to reconcile a region’s economic engine with mounting evidence that the stain‑resistant chemistries it relied on — PFAS, often called “forever chemicals” — persist in the environment and people’s bodies.

How PFAS Became Carpet Country

From the 1970s onward, carpet makers in Dalton and the surrounding region used fluorochemical treatments to give carpets durable stain and soil resistance. Those same properties — strong carbon‑fluorine bonds that make PFAS resistant to breakdown — meant the compounds lingered in wastewater, soil, wildlife and human blood. Internal documents show chemical makers like 3M and DuPont warned industry customers about environmental persistence and detection in human blood by the late 1990s. Yet mills continued to use related formulations for years, and many switched among similar PFAS products that regulators did not yet restrict.

Industry, Utility and Regulatory Failures

Carpet producers routed PFAS‑contaminated wastewater to Dalton Utilities and to treatment processes that could not remove these compounds. The utility’s land‑application site, Loopers Bend, sprayed treated effluent across thousands of acres for decades, allowing PFAS to leach into creeks and the Conasauga River. Dalton Utilities previously pleaded guilty in the 1990s to falsifying wastewater reports, a scandal that weakened trust between regulators and the industry. Attempts by EPA to test facilities in the 2000s were resisted by the industry and the local utility, and Georgia’s state regulators often deferred to federal guidance.

Scientific Findings and Human Impact

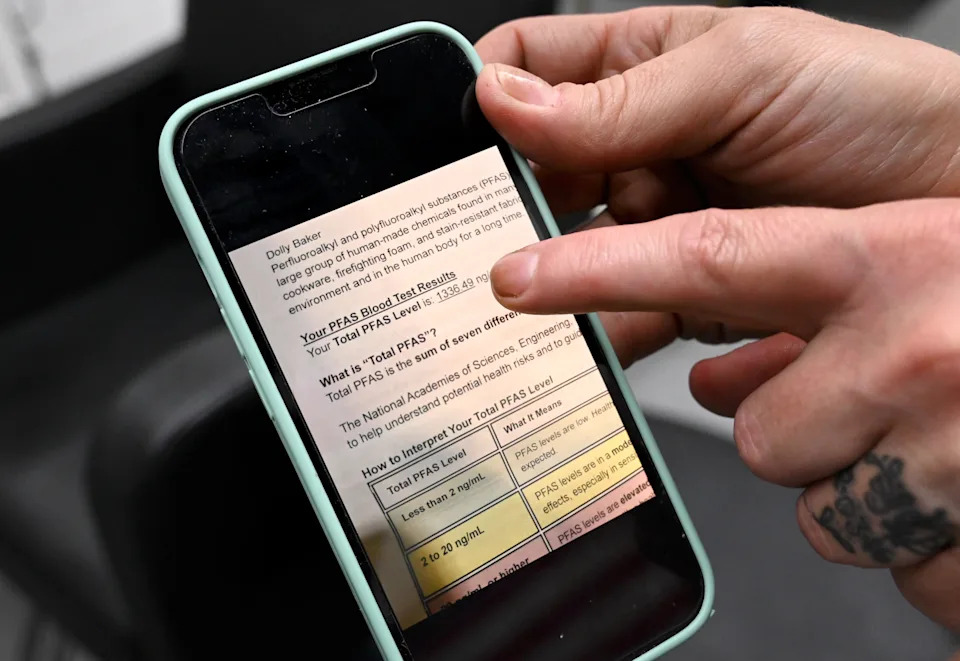

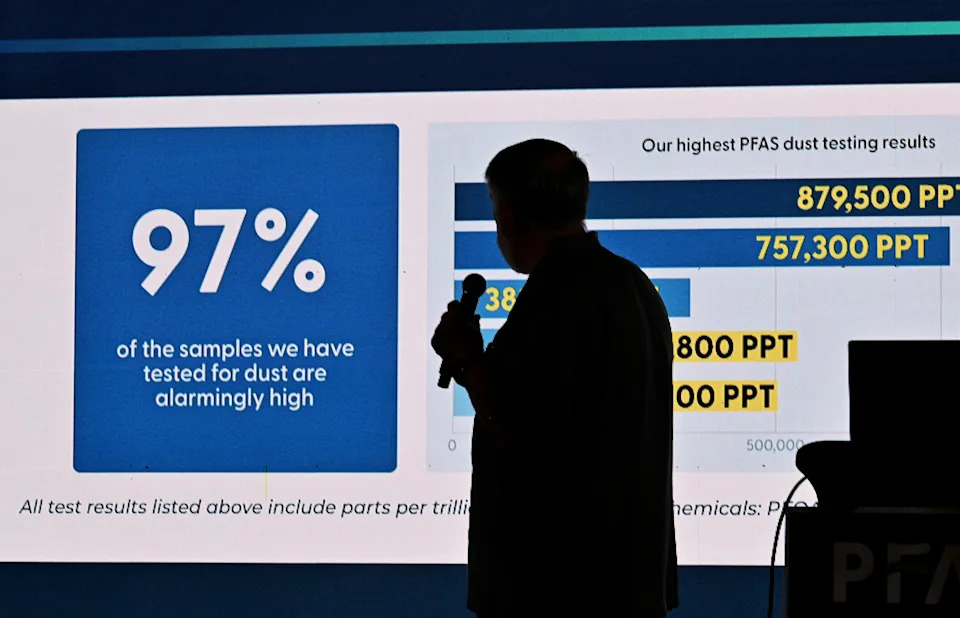

University of Georgia tests published in 2008 found PFAS levels in the Conasauga among the highest ever recorded in surface water. Local and regional testing in subsequent years detected PFAS in river water, private wells, wildlife, household dust and the blood of many residents. An Emory University study (2025) and other tests show a large share of local residents have PFAS concentrations that, by National Academies guidance, warrant medical screening. Residents report thyroid nodules, cancer concerns and other health problems they fear are linked to long‑term exposure.

"I feel like there's a blanket over me, smothering me that I can't get out from under," said one resident who learned her blood levels were extraordinarily high.

Legal And Financial Fallout

Municipalities, water systems and private plaintiffs have filed multiple lawsuits against carpet makers, chemical suppliers and the utility. Rome reached roughly $280 million in settlements; other suits and claims continue. Dalton Utilities itself has sued manufacturers, estimating cleanup and containment could cost hundreds of millions of dollars. Litigation reflects the absence of comprehensive federal PFAS rules for much of the industry’s history and the resulting recourse to courts for accountability.

Industry Shifts And Lingering Risks

Manufacturers phased out older, long‑chain (C8) PFAS and moved to shorter‑chain variants (C6) that retained stain‑fighting properties but may still be persistent and mobile in the environment. Shaw and Mohawk say they ceased using PFAS in U.S. carpet production (Shaw cites 2019), but EPA testing in recent years shows PFAS continue to be detected in industry wastewater. Removing legacy contamination from water, soil and homes remains technically challenging and costly.

What Residents Face Now

Communities downstream face uncertainty about drinking‑water safety, the safety of locally raised food and long‑term health outcomes. Many residents lack affordable access to PFAS blood testing or filtration systems; eligibility for remediation programs can turn on narrow cutoff values. Meanwhile, efforts to craft federal and state rules and funding for cleanup remain politically contested and uneven.

Bottom line: Northwest Georgia’s carpet industry helped build a thriving regional economy but also contributed to widespread PFAS contamination. The human, environmental and financial consequences are unfolding in courtrooms, laboratories and living rooms across the region.

This investigation is a collaboration among The Atlanta Journal‑Constitution, The Associated Press and FRONTLINE (PBS), with reporting contributions from The Post and Courier and AL.com. It accompanies the FRONTLINE documentary “Contaminated: The Carpet Industry’s Toxic Legacy.”

Help us improve.