High-precision uranium–lead dating of microscopic zircon and apatite grains in river sands near Stonehenge finds age signatures consistent with local geology rather than with distant sources in Wales or northeast Scotland. The results weaken the theory that glaciers transported the bluestones and the Altar Stone to Salisbury Plain during the last Ice Age and make human transport more likely. The study, published in Communications Earth and Environment, leaves open how Neolithic people moved these multi-ton stones.

Tiny Mineral Grains Upend a Longstanding Stonehenge Glacier Theory

New high-precision mineral dating has challenged a long-debated idea about how some of Stonehenge’s stones arrived on Salisbury Plain. A recent study analyzed microscopic mineral grains in river sands near the monument and found age signatures consistent with local rocks, weakening the claim that glaciers carried the bluestones and the Altar Stone from Wales and Scotland.

What the Researchers Did

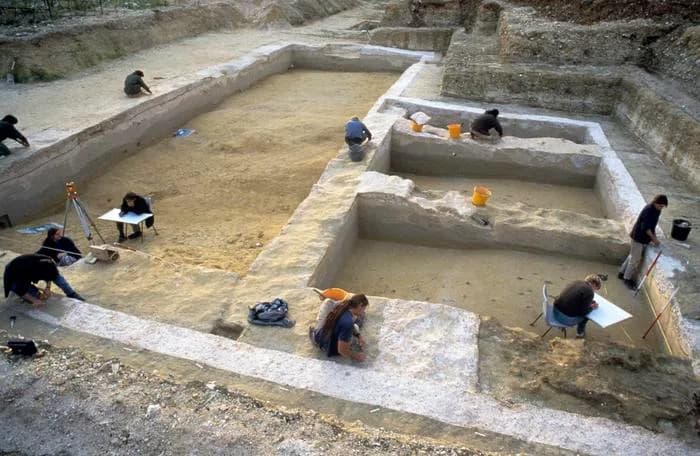

Geologists led by Anthony Clarke of Curtin University used uranium–lead (U–Pb) dating on tiny zircon and apatite grains found in sands around Stonehenge. Zircon and apatite trap trace amounts of uranium when they form, and measuring the uranium-to-lead decay provides an age for each grain. Because rock ages vary across Britain, those grain ages act like a geological fingerprint that can point to a stone’s origin.

The team collected and analyzed river sands from the Salisbury Plain region and compared the grain-age distributions to those expected if glaciers had transported material from Wales (the proposed source for many bluestones, >140 miles away) or from northeast Scotland (the hypothesized origin for the roughly 6-ton Altar Stone, >400 miles away).

Key Findings

Most zircon grains dated between about 1.7 and 1.1 billion years, matching the ages of ancient sedimentary sheets that once covered central southern England. The apatite grains indicate they have been present on Salisbury Plain for tens of millions of years. The study found no clear mineral-age evidence that material from Wales or Scotland was deposited on the plain by glaciers.

“If glaciers had carried rocks all the way from Scotland or Wales to Stonehenge, they would have left a clear mineral signature on the Salisbury Plain,” said Anthony Clarke. The new results, he added, make human transport of the stones a more plausible explanation.

Implications and Remaining Mysteries

By undercutting the long-distance glacial-transport hypothesis, the study strengthens the case that Neolithic people moved at least some of the foreign stones to Stonehenge. Exactly how prehistoric builders hauled multi-ton stones—by rolling logs, sledges, boats or a combination—remains unresolved and is still debated by researchers, much like the questions about moving the large statues of Rapa Nui (Easter Island).

Stonehenge itself likely served multiple roles over centuries—as an observatory, a burial site and a gathering place—and continues to draw more than a million visitors each year. The study, published in Communications Earth and Environment, demonstrates how microscopic evidence can inform big questions about human history and prehistoric technology.

Help us improve.