Researchers used cosmogenic krypton preserved in zircon crystals to reconstruct tens of millions of years of landscape change on Australia’s Nullarbor Plain. Measurements show that around 40 million years ago erosion rates were extremely low—under 1 metre per million years—and that zircon‑rich sands required about 1.6 million years to be transported to the coast. The krypton‑in‑zircon "cosmic clock" explains formation of major zircon deposits like Jacinth‑Ambrosia and can be applied to study surface processes hundreds of millions of years back in time.

A 'Cosmic Clock' in Tiny Zircon Crystals Reveals Australia’s Ancient Landscapes

Tiny mineral grains are telling a very big story about Australia’s past. A new study using cosmogenic krypton trapped in zircon crystals reconstructs how rivers, coasts and habitats in southern Australia changed over tens of millions of years—and explains how rich mineral deposits such as the Jacinth‑Ambrosia zircon field formed.

How cosmic rays write landscape history

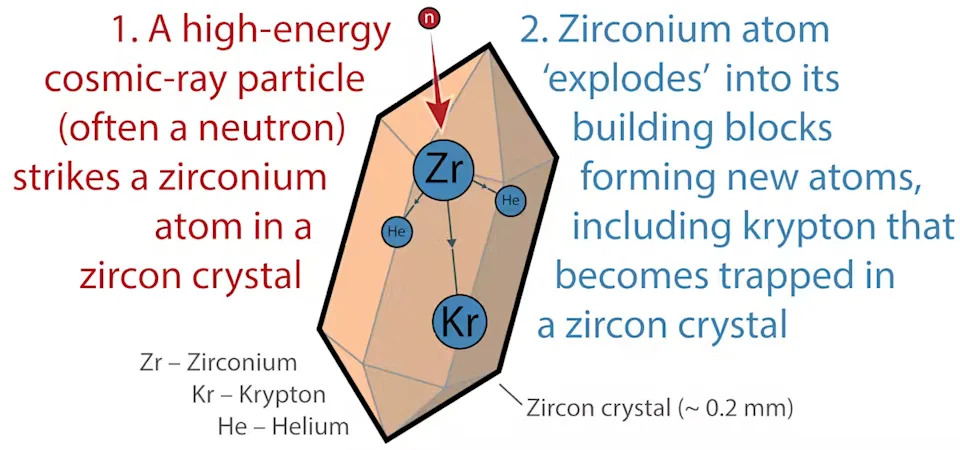

Earth is constantly bombarded by high‑energy particles from space called cosmic rays. When these particles strike atoms near Earth’s surface they trigger tiny nuclear reactions that create cosmogenic nuclides—chemical fingerprints that record how long a mineral has been exposed at the surface. Many cosmogenic nuclides decay too quickly to be useful for very ancient surfaces, but krypton produced in zircon behaves differently.

Krypton in zircon: a durable 'cosmic clock'

Zircon is an exceptionally robust mineral widely used by geologists because it preserves information over geological time. Recent advances now allow scientists to measure cosmogenic krypton trapped inside single zircon grains by vaporizing them with a laser and analysing the released gas. Because krypton is stable (it does not decay), it preserves exposure histories for tens to hundreds of millions of years—far longer than many other cosmogenic markers.

What the Nullarbor buried beaches reveal

By drilling into subsurface sediments on the Nullarbor Plain, researchers recovered fossil beach sands that today lie more than 100 kilometres inland. These sands are unusually rich in zircon and record a dramatic environmental shift: about 40 million years ago southern Australia was warmer and wetter, supporting forests and a much slower pace of landscape change.

The krypton measurements indicate that erosion rates at that time were extremely low—less than one metre per million years. That rate is comparable to some of Earth’s most stable places (for example, parts of the Atacama Desert and Antarctica’s dry valleys) and vastly slower than rates in active mountain belts like the Andes or New Zealand’s Southern Alps.

Researchers estimated the zircon‑rich sands required roughly 1.6 million years to travel from source areas to coastal burial. During this prolonged, slow transport, weaker minerals were destroyed by weathering and physical abrasion, leaving resilient grains such as zircon to become progressively concentrated. Over millions of years, this natural 'filtering' produced economically important concentrations of zircon and other heavy minerals.

Broader implications and future uses

The krypton‑in‑zircon method captures not only long intervals of stability but also transitions: the record shows that subsequent climate shifts, tectonic movement and sea‑level changes eventually accelerated erosion and sediment transport. This explains the concentration of zircon along the Nullarbor margins and helps illuminate the origin of the Jacinth‑Ambrosia deposit, which supplies roughly a quarter of the world’s zircon.

Because both krypton and zircon are chemically stable, the technique can be applied to much older intervals of Earth history—potentially hundreds of millions of years. That opens exciting possibilities, such as testing how the rise of land plants (roughly 500–400 million years ago) altered erosion, sediment transport and landscape stability. Applying the method to modern landscapes, where processes can be directly measured, will refine the approach and expand its utility.

In short: cosmic rays leave a long‑lived signature in zircon that functions as a geological clock, allowing scientists to read deep‑time stories of erosion, transport and deposit formation—and to better predict how landscapes might change in the future.

Original research published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences; this summary synthesises those findings for a general audience.

Help us improve.