A new mineral‑fingerprinting study analyzed over 700 zircon and apatite grains from river sediments near Stonehenge and found no evidence that glaciers deposited the monument’s stones on Salisbury Plain. The results show local geological signatures rather than matches to western Wales or Scotland, supporting the view that humans transported the bluestones from the Preseli Hills (~140 miles/225 km) and that the ~6.6‑ton Altar Stone likely came from northern Britain (~300 miles/500 km), possibly involving boats.

Humans, Not Glaciers: New Study Confirms How Stonehenge's Stones Were Moved

A new study using high-precision mineral fingerprinting finds no geological evidence that ice sheets carried Stonehenge’s most distant stones to Salisbury Plain. The research strengthens the case that people deliberately transported the monument’s bluestones and the large Altar Stone from distant parts of Britain.

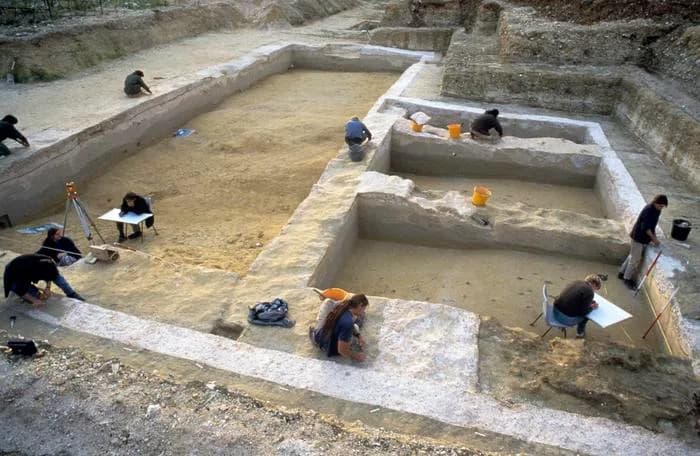

What the researchers did

Scientists analyzed more than 700 microscopic zircon and apatite mineral grains recovered from river sediments in and around the Stonehenge area. Using established radioactive decay systems to date these tiny grains, the team compared their age signatures with known source regions such as the Preseli Hills in western Wales and rock outcrops in northern Britain.

Key findings

The grain ages did not match the signatures expected if glaciers had transported rocks from Wales or Scotland into Salisbury Plain. Instead:

- Most zircon grains dated between about 1.7 billion and 1.1 billion years — ages consistent with ancient basement rocks beneath much of southern England.

- Most apatite grains clustered around ~60 million years, corresponding to a period when southern England was a shallow subtropical sea.

These local age signatures indicate that the river sediments near Stonehenge are derived from nearby geology rather than having been contaminated by glacially transported fragments from distant quarries.

Implications for Stonehenge

The results undercut the "glacial transport" hypothesis — the idea that natural ice sheets delivered the bluestones and the roughly 6.6‑ton (about 6 metric‑tonne) Altar Stone to Salisbury Plain during the last ice age (roughly 2.6 million to 11,700 years ago). Instead, the study supports earlier provenance work showing that:

- The bluestones trace to the Preseli Hills of western Wales, implying people transported them roughly 140 miles (225 km) to the monument.

- The Altar Stone likely originated in northern England or Scotland, a distance of at least ~300 miles (500 km), which may have required boats or complex overland logistics.

"While previous research had cast doubt on the glacial transport theory, our study goes further and applies cutting‑edge mineral fingerprinting to trace the stones' true origins," wrote Anthony Clarke and Christopher Kirkland of Curtin University in The Conversation.

Why this matters

By showing that ice sheets almost certainly did not deliver the monument’s most exotic stones to Salisbury Plain, this work emphasizes the scale of human planning, selection and transport involved in Stonehenge’s construction. It sharpens our understanding of prehistoric people’s capabilities and of the choices they made when sourcing stone from distant landscapes.

Study details: Published Jan. 21 in Communications Earth and Environment; lead authors Anthony Clarke and Christopher Kirkland (Curtin University); analysis based on more than 700 zircon and apatite grains.

Help us improve.