A fresh analysis of remains from the Neolithic Menga Dolmen near Antequera shows two adult males were buried there in the medieval period (8th–11th centuries C.E.). Both were about 45 at death, buried facedown and aligned with the monument’s axis, suggesting ritual reuse. Degraded DNA from one individual indicates ancestry linked to Western Europe, North Africa and the Levant. The study argues the dolmen retained symbolic significance long after its Neolithic construction.

Medieval Burials at Spain’s 6,000‑Year‑Old Menga Dolmen Reveal Long‑Lasting Ritual Significance

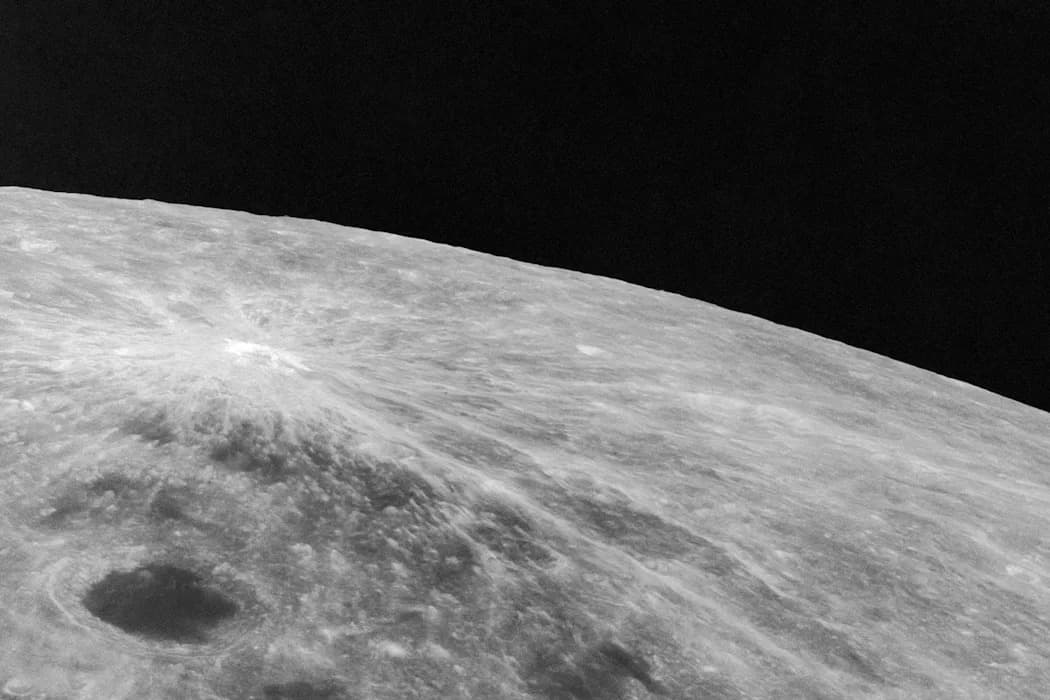

A recent study of degraded human remains from the Neolithic Menga Dolmen, near Antequera in Andalusia, shows that this 6,000‑year‑old megalithic monument continued to hold ritual meaning as late as the medieval period.

What the Researchers Found

Two adult males recovered in 2005 within the UNESCO World Heritage complex were reanalyzed using radiocarbon dating and genetic techniques. The dates place both burials between roughly the 8th and 11th centuries C.E. Each man was about 45 years old at death and was buried facedown, aligned with the central axis of the chamber — a deliberate orientation that links the interments to the monument’s built geometry.

"We propose an interpretation for these inhumations based on historical accounts," the authors write, situating the finds within the broader medieval phenomenon of reusing prehistoric monuments in Iberia (Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports).

Burial Orientation and Cultural Context

Placing a body facedown can be consistent with Islamic-era funerary practices known in medieval Iberia, but the researchers note that the specific alignment with the dolmen’s axis differs from typical Islamic burials recorded locally. That difference suggests the choice of the Menga Dolmen reflected its symbolic or sacred status rather than simply following contemporary burial convention.

DNA and Dating

DNA preservation was poor because the remains were highly degraded, but scientists were able to recover enough genetic information from one individual to detect ancestry components linked to Western Europe, North Africa and the Levant. These genetic signals match broader population patterns documented in southern Iberia during the medieval centuries. Radiocarbon dates and archaeological context together support a medieval, not prehistoric, attribution for these two inhumations.

Why This Matters

The findings reinforce the idea that prehistoric monuments like Menga were not simply abandoned ruins by the Middle Ages. Instead, they could remain meaningful places for new communities, reused and reinterpreted across millennia. The study highlights continuity of symbolic landscape use and the layered way people interact with ancient monuments.

Located near Málaga, the Antequera complex includes three remarkable megalithic monuments built in the Neolithic from massive stone blocks and covered by mounds. UNESCO describes the tombs as among the most remarkable architectural works of European prehistory and central examples of European megalithism.

Research Team and Publication: The study involved specialists from the University of Huddersfield, the University of Seville, Harvard University and the Francis Crick Institute and was published in the Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports.

Help us improve.