Genetic analysis of two Paleolithic skeletons from Grotta del Romito shows they were a mother and daughter who both carried variants in the NPR2 gene, consistent with Acromesomelic Dysplasia (Maroteaux type). DNA from temporal bone material confirmed the family relationship and helped explain differences in stature—Romito 1 likely heterozygous and less severely affected, Romito 2 homozygous and more severely affected. Both individuals survived into late adolescence or adulthood, suggesting sustained social care within their community and highlighting how rare genetic disorders have long existed in human populations.

12,000-Year-Old Embrace Reveals Mother and Daughter Had Rare Bone Disorder

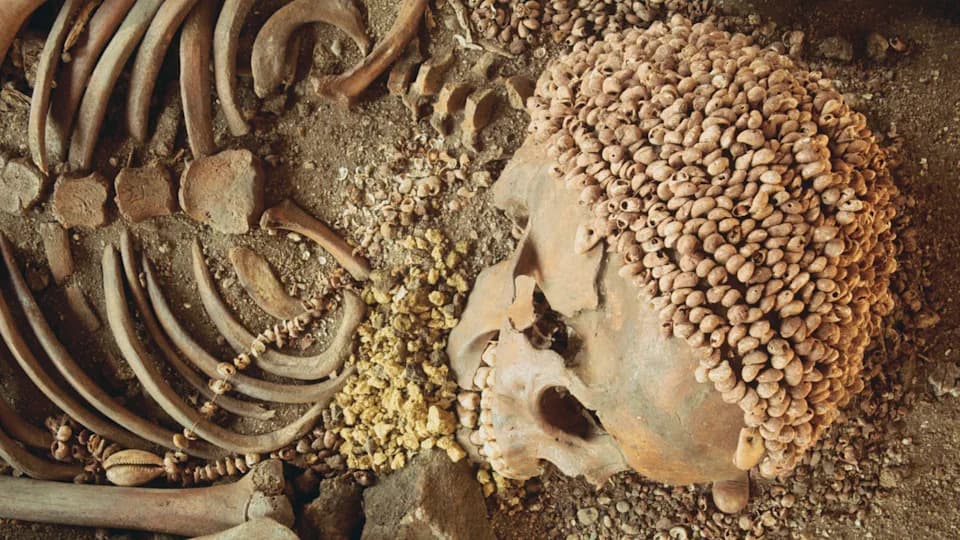

In 1963 paleoarchaeologists excavating Grotta del Romito in southern Italy uncovered an extraordinary burial: two Paleolithic skeletons positioned in an embrace and dated to more than 12,000 years ago. Catalogued as Romito 1 (an older woman) and Romito 2 (a younger female), both skeletons show markedly shortened limbs and estimated statures of about 4.75 feet and 3.6 feet, respectively.

A new genetic study published in the New England Journal of Medicine provides strong evidence resolving longstanding questions about their relationship and physical differences. Scientists extracted DNA from temporal bone samples—a region of the skull that often preserves ancient genetic material well—and confirmed a first‑degree relationship: Romito 1 was the mother and Romito 2 her daughter.

The team identified pathogenic variants in the NPR2 gene, which is important for bone growth. Romito 1 likely carried a heterozygous variant and showed a milder form of the condition, while Romito 2 carried a homozygous variant associated with a more severe outcome. Taken together with the skeletal remains, the evidence supports a diagnosis of Acromesomelic Dysplasia, Maroteaux Type (AMD) in both individuals.

“Identifying both individuals as female and closely related turns this burial into a familial genetic case,” said Daniel Fernandes, an anthropologist at the University of Coimbra. “The older woman’s milder short stature likely reflects a heterozygous mutation, showing how the same gene affected members of a prehistoric family differently.”

Despite mobility challenges that AMD can present, both women appear to have survived into late adolescence or adulthood. The authors argue this implies sustained care and support from their community—for example, help with food, movement, and protection in a hunter‑gatherer environment.

“We believe her survival would have required sustained support from her group, including help with food and mobility in a challenging environment,” said Alfredo Coppa of Sapienza University.

Beyond illuminating compassion and social networks in Paleolithic communities, the study shows that rare genetic diseases have deep roots in human history. As co‑author Adrian Daly of Liège University Hospital Center notes, understanding ancient cases can improve recognition of genetic conditions today and inform medical research into their origins and variation.

Key details: discovery at Grotta del Romito (1963); burials dated >12,000 years; DNA from temporal bone established a mother‑daughter relationship; pathogenic NPR2 variants consistent with Acromesomelic Dysplasia, Maroteaux type; evidence suggests long‑term social support allowed survival into adulthood.

Help us improve.