New research from MaiaSpace (ArianeGroup) presented at EUCASS 2025 warns that the common “Design For Demise” practice—designing satellites to burn up on reentry—may release aluminum oxide nanoparticles that catalyze ozone‑depleting chemistry. A 550‑pound satellite could produce roughly 66 pounds (≈30 kg) of aluminum oxide. The authors propose “Design For Non‑Demise” (D4ND): building satellites to survive reentry and perform controlled ocean splashdowns, but note this approach raises mass, cost and operational challenges.

Burn Or Bury? New Study Says Letting Satellites Survive Reentry Could Protect The Ozone

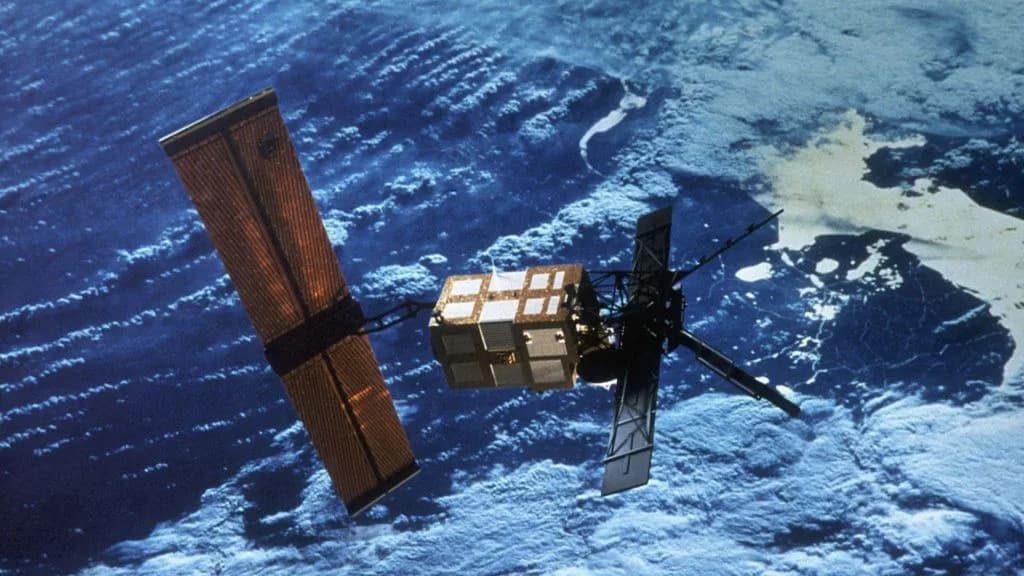

Year after year, decommissioned satellites make a final, fiery plunge toward Earth. Though most vanish from sight, new research warns they leave behind an invisible chemical trail that could be damaging the stratospheric ozone layer.

For decades the aerospace industry has followed “Design For Demise” (D4D): build spacecraft so they burn up on reentry and avoid leaving high‑melting‑point fragments—like titanium or stainless steel—that could strike people on the ground. That approach reduces ground‑impact risk and allows cheaper, uncontrolled disposal while meeting a target fatality probability of less than 1-in-10,000.

But a paper presented at the European Conference for Aerospace Sciences (EUCASS 2025) by Antoinette Ott and Christophe Bonnal of MaiaSpace (an ArianeGroup subsidiary) argues D4D may be creating a secondary environmental problem.

“Design For Demise (D4D) minimises ground risks by maximising re‑entry burn‑up; Design For Non‑Demise (D4ND) aims to reduce high‑altitude emissions, but it may require controlled descents and extra mass,” the paper notes.

The researchers say ablation during reentry converts solid metals into a fine mist of chemicals, aerosols and reactive gases. The chief concern is aluminum oxide: a typical 550‑pound (≈250 kg) satellite is roughly 30% aluminum and, when it ablates, could generate about 66 pounds (≈30 kg) of aluminum oxide nanoparticles.

Those microscopic particles can act as catalysts in reactions between atmospheric chlorine and ozone, potentially accelerating ozone depletion. The authors also report an apparent “eightfold increase” in concentrations of these harmful oxides over a recent six‑year period, signaling a rising cumulative impact as satellite numbers grow.

Design For Non‑Demise (D4ND): Pros And Cons

Ott and Bonnal advocate a “Design For Non‑Demise” (D4ND) alternative: build satellites to survive reentry and perform controlled descents to remote ocean areas, avoiding the release of reactive aerosols into the stratosphere. In theory, intact vehicles would be steered to safe splashdowns, preserving both atmospheric and ground safety.

But D4ND brings real challenges. Satellites would need stronger structures, heavier propulsion systems, and more fuel—adding mass that raises launch costs and reduces payload efficiency. Implementing D4ND also requires reliable end‑of‑life guidance, international coordination, and new regulatory and economic models to account for the tradeoffs.

What’s Next?

Currently there is no unified metric to compare the low but nonzero ground‑risk from surviving debris against the slow, global risk of atmospheric damage. With mega‑constellations planning tens of thousands of additional satellites, the industry faces a growing choice: prioritize minimal ground risk via burn‑up, or accept higher design and operational costs to limit cumulative atmospheric harm.

The paper does not claim an immediate catastrophe, but it urges a broader, longer‑term view of safety that includes the upper atmosphere. Policymakers, operators and manufacturers will need to weigh economic costs, technical feasibility and environmental stewardship as satellite deployments scale up.

Help us improve.