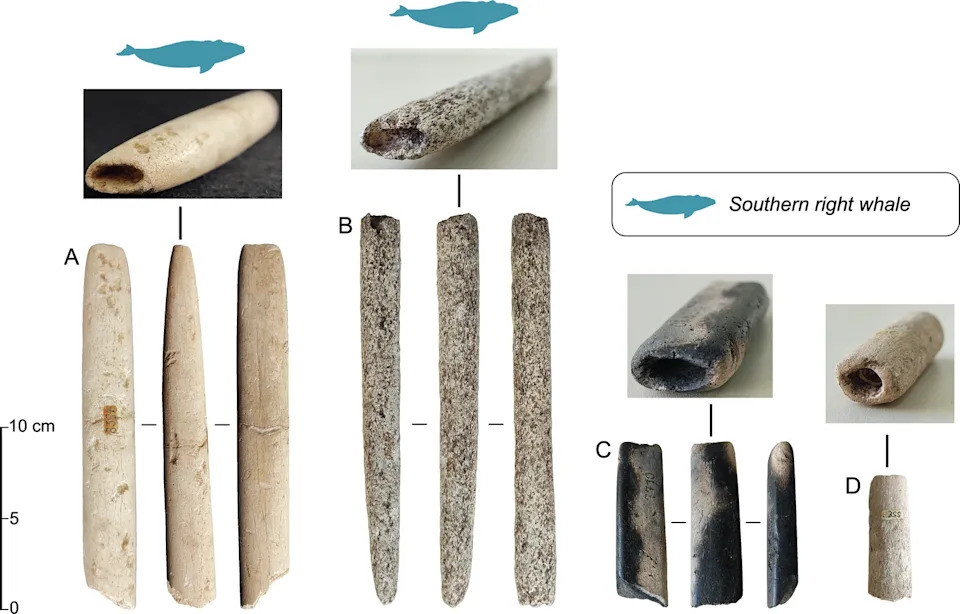

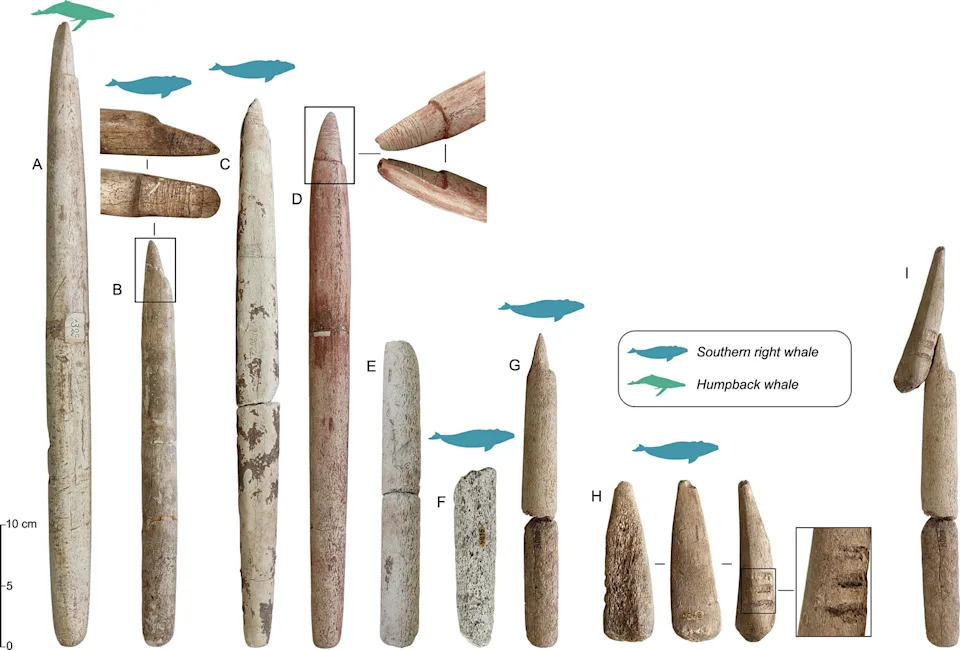

Researchers analyzed 118 cetacean bones and identified 15 harpoon elements made from humpback and southern right whale ribs at the Joinville Sambaqui Archaeological Museum. Radiocarbon dating of two foreshafts returned ages between 4,710 and 4,970 years, ranking these among the oldest known harpoon components. The study, published in Nature Communications, suggests Sambaqui communities in southern Brazil actively hunted large whales, expanding our view of prehistoric maritime practices beyond the Northern Hemisphere.

Ancient Bone Harpoons Reveal Sambaqui Communities in Brazil Hunted Whales About 5,000 Years Ago

Harpoons carved from the rib bones of humpback and southern right whales show that Indigenous Sambaqui communities in what is now southern Brazil were actively hunting large whales roughly 4,700–5,000 years ago. The find — including 118 identifiable cetacean bones and 15 worked harpoon elements — was analyzed by researchers and reported in the journal Nature Communications.

What Was Found

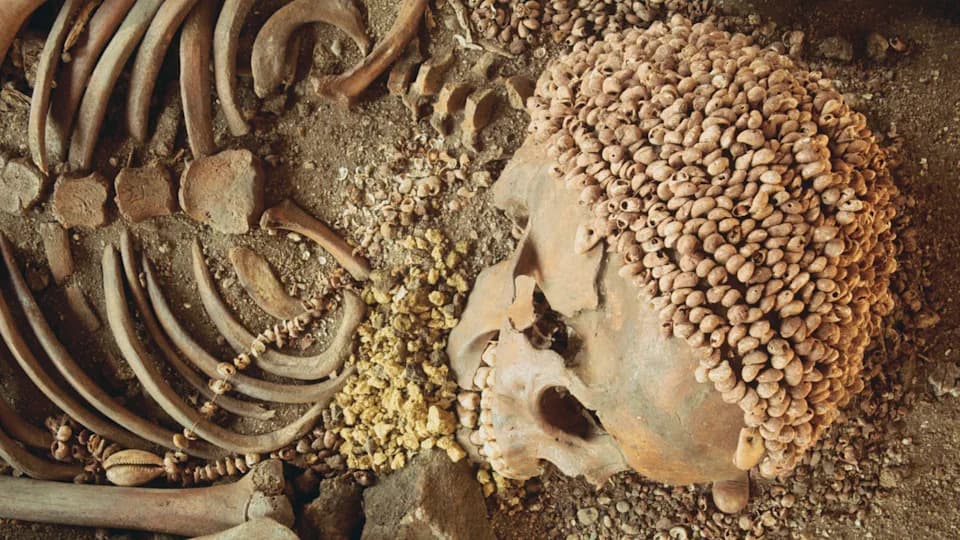

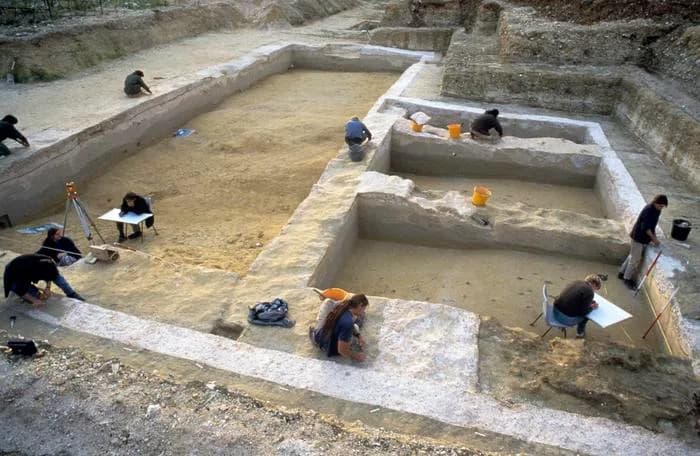

Researchers examined cetacean remains stored at the Joinville Sambaqui Archaeological Museum. Of the 118 bones that could be identified to species, most belonged to southern right whales and many to humpback whales. The team also documented 37 worked bones fashioned into items such as pendants and, unexpectedly, 15 harpoon elements — heads and shaft fragments — made from whale ribs.

Dating and Significance

Tiny samples were taken from two harpoon foreshafts for radiocarbon dating. The results returned calibrated ages between 4,710 and 4,970 years before present, making these some of the oldest known harpoon components in the world — more than a millennium older than comparable finds from Arctic and sub-Arctic regions. The co-occurrence of multiple worked tools and numerous bones from the same species strengthens the interpretation that these communities engaged in deliberate whaling rather than solely scavenging stranded whales.

Methods and Interpretation

The analysis combined molecular identification of cetacean bones with microscopy and functional assessment of the carved bone pieces. Several harpoon elements show hollowed centers suitable for a wooden shaft and carved tips consistent with hunting weapons. While it is possible some tools were used on other large marine mammals (for example, large seals), the species-specific bone sourcing and tool design support the whaling hypothesis.

"Whaling has always been enigmatic," said André Carlo Colonese, research director at the Autonomous University of Barcelona and a co-author of the study, adding that it's often difficult in the archaeological record to separate tools made from hunted animals from those made from stranded ones.

Why This Matters

This discovery challenges the long-standing view that prehistoric whaling was concentrated in northern temperate and polar regions. It shows that tropical and subtropical coastal societies in South America had the technology, organization and maritime knowledge to pursue large whales thousands of years ago. The findings broaden our understanding of ancient maritime economies and the diverse ways coastal peoples exploited marine resources.

Caveats

Although the evidence is strong, researchers note that direct proof of whales struck and killed by these specific harpoons (such as embedded tips in whale bones) remains lacking. Future excavations and contextual analyses may further clarify hunting techniques, seasonal patterns, and the social organization behind prehistoric whaling in the region.

Publication: Study published Jan. 9 in Nature Communications. Materials are curated at the Joinville Sambaqui Archaeological Museum, Brazil.

Help us improve.