China's FAST telescope is re-observing 100 candidate narrowband signals originally identified by the citizen-science project SETI@home (1999–2020), which produced about 12 billion initial hits. Supercomputing filters at the Max Planck Institute reduced those to 1 million, then 1,000, then 100 candidates now under targeted follow-up by FAST. While researchers expect most to be radio frequency interference, the campaign tightens sensitivity limits and offers lessons for future machine-learning reanalyses of archival data.

SETI's Final 100: China's FAST Rechecks Century-Old Signals — Could One Be From Aliens?

A team of astronomers is using China's giant Five-hundred-meter Aperture Spherical Telescope (FAST) to re-observe 100 intriguing candidate signals originally flagged by the citizen-science project SETI@home. The campaign aims to confirm whether any of these century-old detections are genuine extraterrestrial transmissions or the more prosaic radio frequency interference (RFI) that routinely plagues radio astronomy.

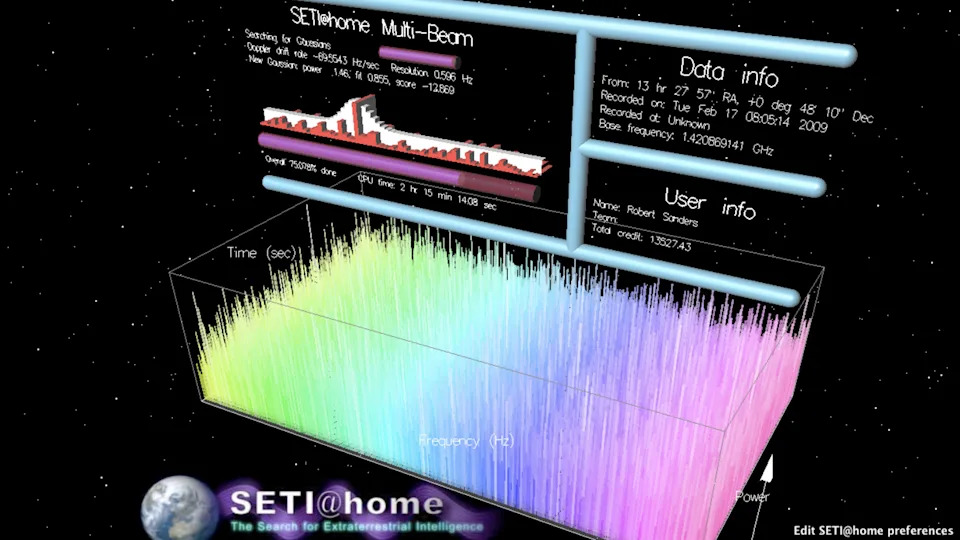

Background: The SETI@home Effort

SETI@home ran from 1999 until 2020 and relied on millions of volunteers donating spare CPU time to analyze radio data collected by the Arecibo Observatory in Puerto Rico. Over the course of the project, distributed computing flagged roughly 12 billion candidate narrowband signals — short, highly localized spikes of power at specific frequencies and sky positions.

From Billions to 100

Researchers used a combination of automated filters and manual inspection to pare the initial list down. At the Max Planck Institute for Gravitational Physics in Germany, supercomputing algorithms designed to identify and remove likely RFI reduced the pool from 12 billion to about 1 million, then to 1,000. Those thousand detections were examined by eye and trimmed to a final set of 100 candidates that merited targeted follow-up.

FAST Follow-Ups

FAST began methodically re-observing those 100 candidates in July 2025. FAST's 500-meter aperture and modern instruments make it the only facility currently capable of probing these faint narrowband signals at the sensitivity required. Arecibo — which had a 305-meter dish — collapsed in December 2020 and can no longer be used for follow-up work.

"Until about 2016, we didn't really know what we were going to do with these detections that we'd accumulated," said David Anderson, a SETI@home co-founder and computer scientist at the University of California, Berkeley. "We hadn't figured out how to do the whole second part of the analysis."

Berkeley astronomer Eric Korpela, another SETI@home co-founder, added: "There's no way that you can do a full investigation of every possible signal that you detect, because doing that still requires a person and eyeballs."

What Researchers Expect — And What a Null Result Means

Based on decades of experience, the SETI@home team cautions that local radio interference is the most likely explanation for most — if not all — of the remaining candidates. Even so, targeted FAST observations are scientifically valuable: if no extraterrestrial signal is found, the campaign will tighten limits on how strong a transmissible signal would need to be to have been detectable, effectively establishing a new sensitivity benchmark.

Legacy and Lessons

SETI@home vastly exceeded the founders' early expectations for volunteer participation: the team initially hoped for tens of thousands of volunteers but reached roughly 2 million users within a year. The project also offers lessons for future searches: the team acknowledges some limitations in early analysis choices driven by the computing constraints of 1999 and emphasizes the need to better quantify what searches exclude so genuine signals aren't inadvertently discarded.

Researchers have suggested a possible future reanalysis of the archival data using modern machine learning and crowd-sourced computing to search for signals missed by earlier pipelines. "There's still the potential that ET is in that data and we missed it just by a hair," Korpela said.

Publications

The overall SETI@home results were summarized in two papers published in 2025 in The Astronomical Journal: one focused on data analysis and findings, the other on data acquisition and processing.

Help us improve.