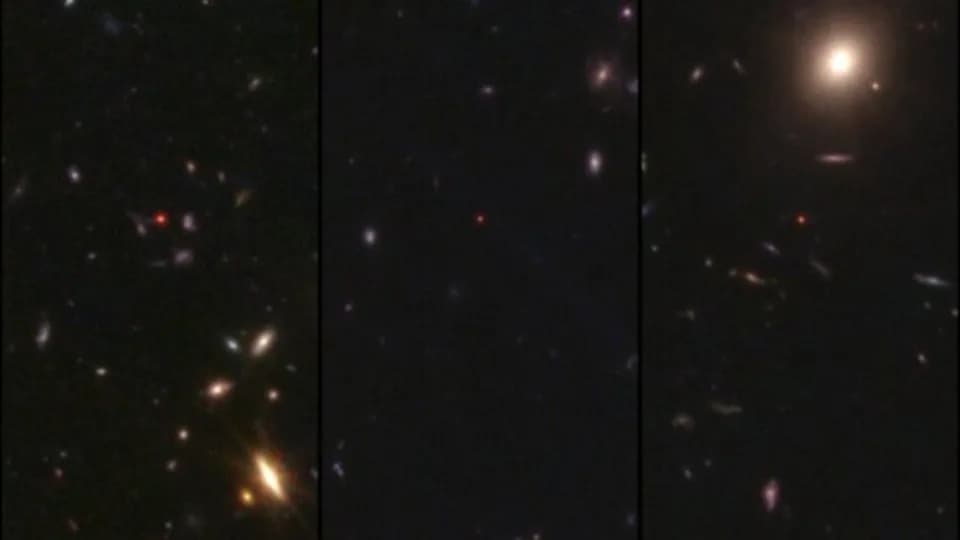

New analysis of 12 compact sources discovered by JWST suggests the so-called “little red dots” are young supermassive black holes hidden inside dense ionized gas cocoons. The objects are far too bright and compact to be explained by stars alone—some regions shine like >250 billion Suns but fit inside less than one-third of a light-year. Gas velocities imply black hole masses of roughly 100,000–10 million solar masses, offering new clues to early black-hole formation.

JWST’s “Little Red Dots” May Be Young Supermassive Black Holes Cloaked in Gas

New modeling of compact, red-hued sources first seen by the James Webb Space Telescope suggests these mysterious “little red dots” are not unusually dense star clusters but young, enshrouded supermassive black holes. The results help resolve why the objects are extremely bright yet lack the usual X-ray and radio signatures of active black holes.

Discovery and Early Debate

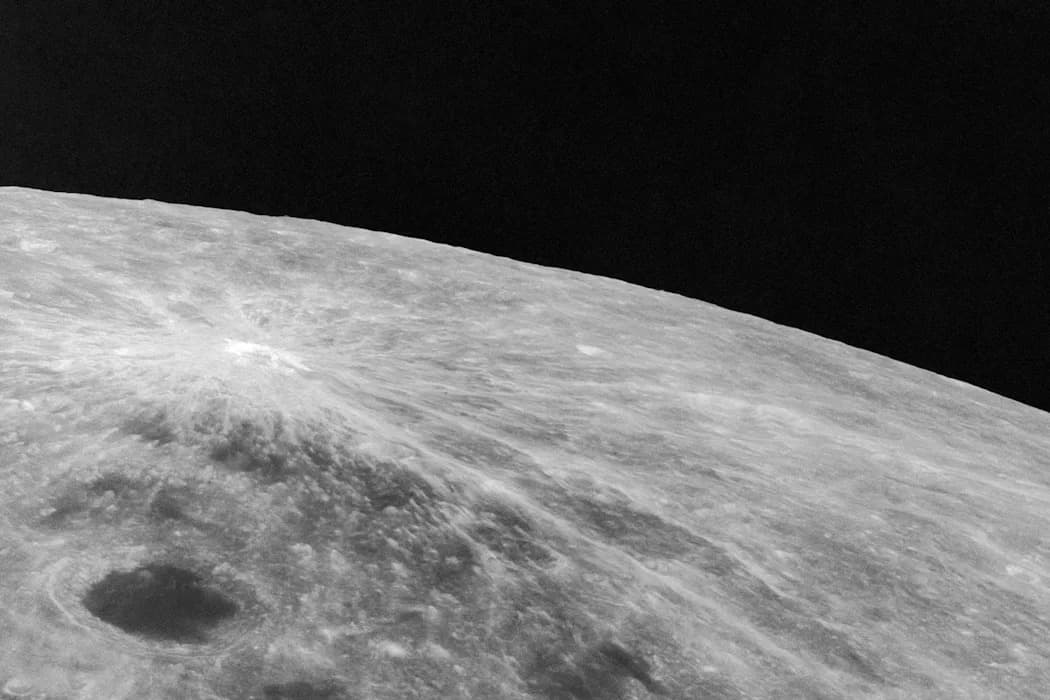

NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) revealed the tiny red specks at the end of 2022. The objects appear in a narrow window of cosmic time: they emerge when the universe was younger than 1 billion years after the Big Bang and largely fade by about 2 billion years after the Big Bang. Their compact size and intense brightness sparked debate over whether they were ultra-dense stellar systems or black holes in an early, active phase.

What the New Study Shows

Researchers analyzed a sample of 12 sources, including objects from when the universe was roughly 840 million years old. Their spectral modeling found that many of the little red dots are both far too luminous and far too compact to be explained by starlight alone.

"They are simply too luminous and too compact to be explained by a large number of stars," said study lead author Vadim Rusakov of the University of Manchester.

The brightest compact components reach luminosities comparable to more than 250 billion Suns while being confined to regions smaller than about one-third of a light-year. For scale, the distance from the Sun to its nearest stellar neighbor, Proxima Centauri, is about 4.25 light-years.

Why X-Rays and Radio Waves Are Missing

Spectral shapes indicate that much of the original high-energy radiation was scattered by electrons in dense, ionized gas cocoons around the central sources. These cocoons can absorb and reprocess radiation, effectively hiding the X-ray and radio emission that normally identifies actively accreting black holes. Rusakov described the effect as an almost perfect disguise that removes typical signatures of massive black holes.

Mass Estimates and Implications

By measuring spectral line widths, the team estimated gas speeds of about 670,000 miles per hour (≈1.08 million km/h). If that gas is orbiting central black holes, the implied masses are roughly 100,000 to 10 million times the mass of the Sun. Those values are about 100 times smaller than some earlier extreme estimates and fit expectations for nascent supermassive black holes in the early universe.

These findings open a new observational window onto how supermassive black holes form and grow. The leading formation scenarios include steady growth from smaller seeds or the rapid creation of intermediate-mass black holes from collapsing gas streams. Follow-up observations could reveal chemical or physical clues in the cocoons that distinguish among these possibilities.

Publication: The study’s results appear in the Jan. 15 issue of the journal Nature.

Help us improve.