2026 promises to be a landmark year for space exploration: next-generation space telescopes will begin wide-field surveys, human crews will fly beyond low Earth orbit for the first time since Apollo, and nations will launch missions to study moons, seek water ice and improve space-weather forecasting. Key observatories include NASA’s Roman, ESA’s PLATO and China’s Xuntian, complemented by the Vera C. Rubin Observatory. Human milestones such as Artemis II and India’s Gaganyaan, plus cooperative missions like ESA–China’s SMILE, highlight a mix of competition and collaboration driving modern space science.

2026: A Pivotal Year for Space — Flagship Telescopes, Lunar Flybys and Global Cooperation

In 2026, humanity’s exploration of space is set to accelerate: powerful new observatories will begin sweeping surveys of the cosmos, crewed missions will travel beyond low Earth orbit for the first time since Apollo, and an array of national programs will chase samples, water ice and clues about how our solar system formed. Taken together, these missions mark both a scientific turning point and a renewed era of international cooperation — and competition — in space.

Flagship Telescopes: Mapping The Universe At Unprecedented Scale

NASA’s Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope completed construction at Goddard and, if schedules hold, could launch as early as fall 2026. Roman’s 300-megapixel camera will image regions roughly 100 times larger than Hubble’s field of view while preserving similar sharpness. During a five-year primary mission, Roman is expected to discover tens of thousands of exoplanets (projections commonly cite >100,000 detections when including microlensing surveys), map billions of galaxies, and sharpen constraints on dark matter and dark energy. Roman also carries a technology-demonstration coronagraph to block starlight and directly image nearby planets — a step toward future missions like NASA’s planned Habitable Worlds Observatory.

ESA’s PLATO (PLAnetary Transits and Oscillations of Stars) is due to launch on Ariane 6 in December 2026. With 26 cameras monitoring ~200,000 stars, PLATO will search for small, rocky planets in habitable zones and measure stellar ages — data critical for assessing planetary habitability.

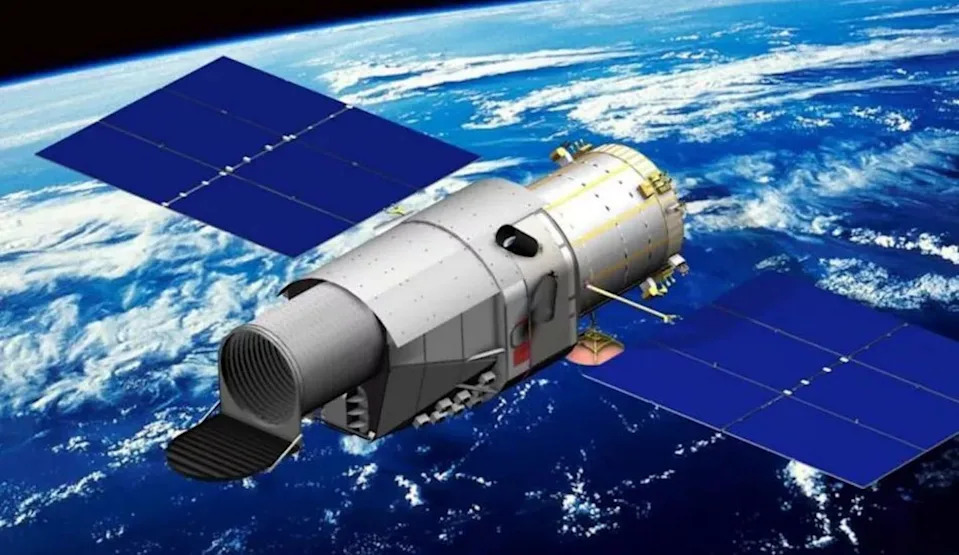

China’s Xuntian Telescope (the Chinese Space Station Telescope) is expected in late 2026. With image quality comparable to Hubble but a field of view >300 times larger, Xuntian will survey enormous sky areas, targeting dark matter, dark energy and the evolution of cosmic structures. Its planned co-orbit with the Tiangong space station would allow servicing and upgrades, potentially extending its operational life.

On the ground, the Vera C. Rubin Observatory will repeatedly scan the southern sky, complementing the space observatories by tracking how the universe changes over time. Together, these facilities will let astronomers study not just static snapshots but cosmic evolution across billions of years.

Human Spaceflight: Returning Beyond Low Earth Orbit

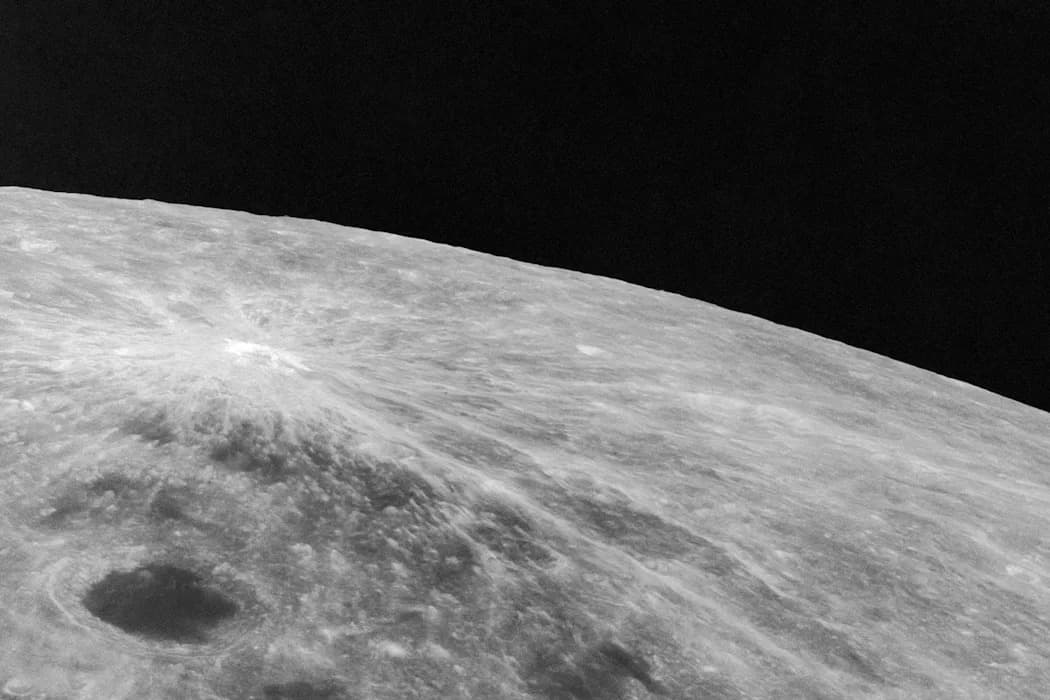

NASA’s Artemis II is preparing for a possible launch in 2026 that would carry four astronauts on a roughly 10-day lunar flyby — the first human mission beyond low Earth orbit since Apollo 17 (1972). This mission is a key step toward sustained lunar exploration and eventual crewed lunar landings later in the decade.

India’s Gaganyaan program plans a series of uncrewed test flights in 2026 as it advances toward independent human spaceflight. If crewed flights follow successfully, India would join a small group of nations capable of launching humans from its own soil.

China will continue regular crewed missions to the Tiangong space station as it builds experience, infrastructure and technologies aimed at future crewed lunar missions. Meanwhile, NASA increasingly relies on commercial crewed spacecraft for low Earth orbit missions, freeing agency resources for deep-space exploration.

Planetary Science And Resource Exploration

Japan’s Martian Moons eXploration (MMX) mission, targeted for late 2026, will visit Mars’ moons Phobos and Deimos, spend around three years studying them, and return a Phobos surface sample to Earth by about 2031. That sample could resolve whether the moons are captured asteroids or the result of a giant impact.

China’s Chang’e 7, expected in mid-2026, will target the Moon’s south pole with an orbiter, lander, rover and a small hopping vehicle designed to access permanently shadowed regions suspected to contain water ice — a resource with major implications for future crewed operations and in-space propellant production.

These missions underscore how planetary science and in-situ resource assessment are increasingly linked: understanding geology and volatile reservoirs informs both science and future human activity.

Space Weather, Earth Protection And International Cooperation

Strong solar storms in 2025 highlighted how solar activity can disrupt aviation, communications and power systems. In response, understanding space weather remains a priority.

SMILE (Solar wind Magnetosphere Ionosphere Link Explorer), a joint mission from ESA and the Chinese Academy of Sciences slated for spring 2026, will produce the first global images of how Earth’s magnetic field responds to the solar wind. Those observations will improve forecasts that protect satellites, electric grids and crewed missions.

SMILE is also notable as an example of meaningful scientific collaboration at a time of growing geopolitical tension in space.

Competition And Cooperation

2026’s missions play out against a complex geopolitical backdrop: the United States and China aim to return humans to the Moon by the decade’s end, while other nations expand independent capabilities. Yet science remains deeply collaborative: instruments and teams often cross national lines (for example, MMX carries instruments contributed by NASA, ESA and French partners). Data sharing and multinational teams continue to be central to modern space science.

Conclusion

The slate of missions planned for 2026 — from wide-field space telescopes to human lunar flybys and sample-return expeditions — reflect a moment when ambition, technology and international partnerships converge. Competition is real, but so is cooperation at a scale that stretches decades into the future. Whether searching distant habitable worlds or probing the Moon’s ice, the year promises discoveries that will shape astronomy and exploration for years to come.

Originally written by Grant Tremblay (Smithsonian Institution) for The Conversation. This version has been edited for clarity, flow and accessibility.

Help us improve.