Laboratory experiments on tiny iron–silicon–carbon alloys, combined with theoretical modeling, show that trace amounts of silicon and carbon change iron’s crystal alignment (LPO) under extreme pressures and elevated lab temperatures. Models based on those measurements reproduce seismic-wave anomalies observed in the outer inner core. The findings support a layered inner-core model: a silicon- and carbon-poor center with strong anisotropy and outer inner-core layers richer in light elements with reduced anisotropy. The study is published in Nature Communications.

Earth’s Inner Core May Be Layered Like an Onion, Lab Tests and Models Suggest

Seismic waves that pass through Earth’s inner core have long revealed surprising properties of our planet’s iron heart — from changing shapes and strange textures to shifts in its rotation and even an unexpected state of matter. A new laboratory-and-modeling study now proposes a chemical layering of the inner core, much like the layers of an onion, driven by variations in silicon and carbon concentrations.

Laboratory Tests and What They Measured

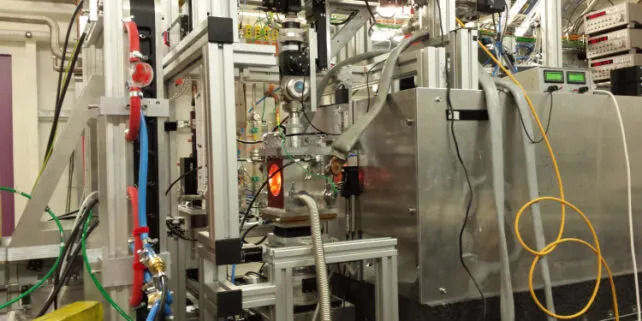

Researchers in Germany created minute iron–silicon–carbon alloy samples, then compressed and heated them under extreme pressures and laboratory temperatures (up to about 820 °C) to probe how these light elements affect iron’s crystal behavior. Using X-ray diffraction, they searched for lattice-preferred orientation (LPO) — the tendency of crystals to align in specific directions due to stress and thermal history — which can strongly influence how seismic waves travel through a solid metal.

“There have been several hypotheses for the origin of these anisotropies,” says mineralogist Carmen Sanchez-Valle of the University of Münster. “We set out to study the combined effect of silicon and carbon on the deformation behavior of iron.”

After the experiments the team analyzed diffraction patterns to derive plastic properties such as yield strength and viscosity for the alloys. Those measurements were then fed into theoretical models and extrapolated to the much higher pressures and temperatures expected in Earth’s inner core.

Results: How Composition Affects Seismic Signals

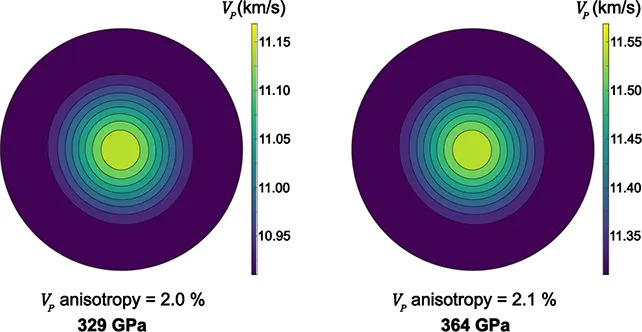

The experiments show that adding silicon and carbon changes the iron crystal lattice’s preferred orientation compared with pure iron. When the researchers modeled how those altered LPO patterns would affect seismic-wave speeds, the predicted velocity variations reproduced anomalies observed in the outer portion of the inner core.

From these results the team proposes a depth-dependent structure: a central inner-core region relatively poor in silicon and carbon, producing stronger seismic anisotropy, surrounded by outer inner-core layers increasingly enriched in light elements where anisotropy is reduced.

Implications

By combining small-scale laboratory experiments with modeling that extrapolates to core conditions, the study provides a plausible mechanism linking core crystallization and chemical stratification to the depth-dependent seismic patterns recorded by global seismology. The research, published in Nature Communications, offers a testable explanation for previously puzzling seismic observations and adds detail to our picture of Earth’s deep interior.

“The depth-dependent anisotropy pattern observed in the Earth's inner core may result from chemical stratification of silicon and carbon following core crystallization,” the authors conclude.

Help us improve.