Perihelion is the point in Earth’s orbit when the planet is closest to the Sun; in 2026 it falls on Jan 3 at 12:15 p.m. EST (17:15 UTC). The distance difference between perihelion and aphelion is modest—about 91.4 million miles vs. 94.5 million miles—and seasons are driven mainly by Earth’s 23.5° axial tilt, not distance. Perihelion increases incoming solar intensity by roughly 7% and makes Earth travel about 2,000 mph faster, slightly altering season length; on long timescales orbital eccentricity contributes to Milankovitch cycles that influence ice ages.

Perihelion Explained: Why Earth Is Closest to the Sun Around January 3, 2026

At the start of each year Earth reaches a quiet orbital milestone called perihelion—the point in its orbit when our planet is nearest the Sun. In 2026, perihelion occurs on January 3 at 12:15 p.m. EST (17:15 UTC). Although this might seem surprising because the Northern Hemisphere is in winter at that time, seasons are driven mainly by Earth’s tilt, not its distance from the Sun.

What Is Perihelion?

Earth’s orbit is an ellipse, not a perfect circle, so the distance between Earth and the Sun changes over the year. Perihelion is the moment when that distance is smallest; the opposite point, when Earth is farthest, is called aphelion. At perihelion Earth is about 91.4 million miles from the Sun versus roughly 94.5 million miles at aphelion in July.

Why Perihelion Doesn’t Cause Seasons

Seasons are primarily caused by Earth’s 23.5° axial tilt, which alters day length and the angle at which sunlight strikes the surface. Tilt-driven changes can alter solar energy reaching mid-latitudes by roughly 50% (and even more at high latitudes). By comparison, the extra sunlight at perihelion boosts solar intensity by only about 7% compared with aphelion, so distance has a much smaller effect than tilt.

“Earth’s axial tilt is the main driver of our seasons,” says Seth McGowan, president of the Adirondack Sky Center. “Distance to the Sun makes only a modest difference.”

What Perihelion Does Affect

Perihelion influences orbital speed and slightly changes the length and intensity of seasons. Kepler’s second law implies that Earth moves faster when it is closer to the Sun. Near perihelion Earth travels roughly 2,000 miles per hour faster than at aphelion. That small speed difference makes the seasons occurring around early January progress a few days faster than those around July.

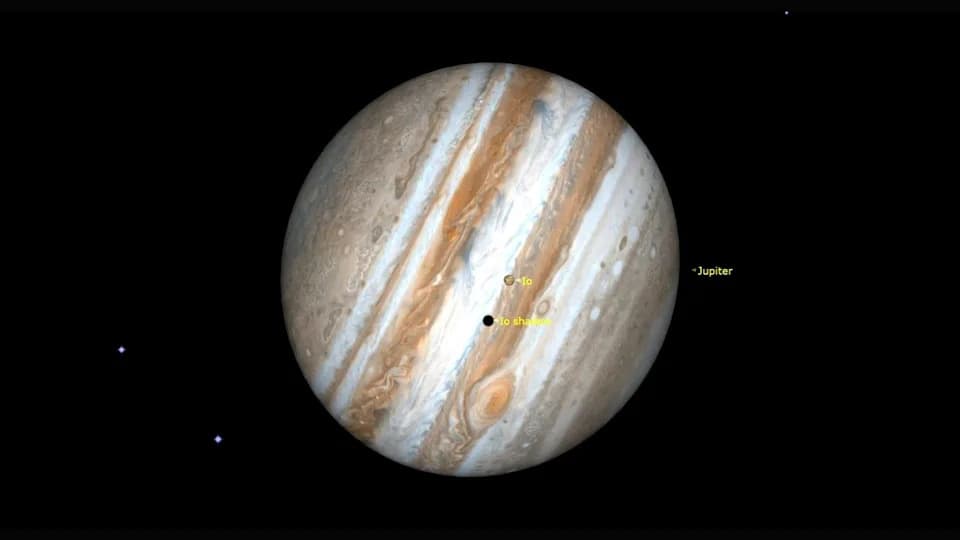

The timing of perihelion also shifts by hours from year to year because gravitational interactions with other bodies—especially the Moon and Jupiter—perturb Earth’s orbit. For mission planning and precise astronomy, those shifts matter.

Long-Term Climate Links

On much longer timescales, changes in Earth’s orbital shape (eccentricity) contribute to the Milankovitch cycles, which influence the timing of ice ages. Eccentricity oscillates on roughly 100,000-year timescales and is currently decreasing slightly; combined with changes in axial tilt and precession, these orbital variations help drive glacial and interglacial periods recorded in ice cores.

Practical Reasons to Track Perihelion

Scientists and space agencies monitor Earth’s precise orbital position for practical reasons: asteroid-impact risk assessment, satellite and navigation planning, and deep-space mission design all require accounting for Earth’s changing velocity and position around the Sun.

Perihelion usually passes without dramatic visual signs, but it’s a useful reminder of the subtle gravitational choreography that shapes seasons and long-term climate rhythms on our planet.

Help us improve.