UC Berkeley scientists used 20 years of satellite data to produce a high-resolution map showing that seasonal cycles often fall out of sync across nearby regions. These asynchronies are common in biodiversity hotspots and can change resource timing, reproduction and long-term evolution. The findings call for finer-scale seasonal data in climate, conservation and agricultural models; related Arctic research suggests expanding nitrogen-fixing microbes could alter algae growth and CO2 uptake.

New Satellite Map Reveals Earth's Seasons Often Fall Out of Sync — With Big Ecological Consequences

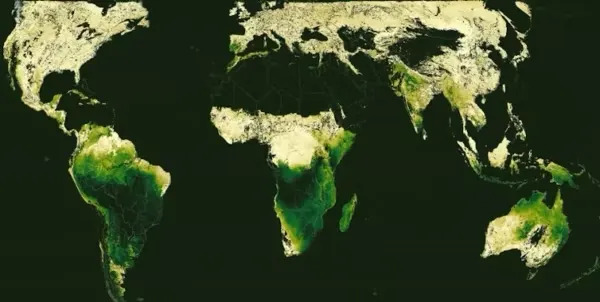

Scientists at the University of California, Berkeley, have used two decades of satellite observations to create the most detailed global map yet of seasonal timing across terrestrial ecosystems. Their analysis shows that spring, summer, autumn and winter do not arrive in unison everywhere — even places that are nearby, at similar latitudes or comparable altitudes can follow very different seasonal calendars.

Seasonal Time Zones Drawn by Nature

Regions that sit side by side can experience different weather and ecological rhythms, producing sharply contrasting habitats across short distances. In some cases, the boundary between seasonal regimes can be as abrupt and consequential as a man-made time zone.

"Seasonality may often be thought of as a simple rhythm — winter, spring, summer, fall — but our work shows that nature's calendar is far more complex," said biogeographer and lead author Drew Terasaki Hart when the map was released. "This can have profound implications for ecology and evolution in these regions."

How The Map Was Made

Using 20 years of satellite data, Terasaki Hart and colleagues quantified the timing of vegetation growth, flowering and other seasonal signals across the globe. The resulting map highlights places where seasonal cycles are particularly asynchronous — a pattern that frequently coincides with biodiversity hotspots.

Why Timing Matters

When adjacent habitats provide food, water or breeding conditions at different times of year, species may shift their life cycles accordingly. That temporal separation can reduce interbreeding between populations and, over many generations, promote divergence and even speciation.

For example, Phoenix and Tucson in Arizona lie only about 160 kilometers (99 miles) apart but follow different rainfall rhythms: Tucson gets much of its rain in the summer monsoon, while Phoenix receives more precipitation in January. Those contrasts cascade through local ecosystems, affecting plant growth, pollinators and agricultural schedules.

Notable Patterns

- Earth's five Mediterranean-climate regions (California, central Chile, parts of South Africa, southern Australia and the Mediterranean Basin) showed forest growth cycles that peak roughly two months later than many other ecosystems.

- The map explains local differences in agricultural timing — for example, coffee harvest seasons in Colombia can vary dramatically across mountain ranges so that farms a day's drive apart harvest at very different times.

Broader Implications

The study argues that climate, conservation and agricultural models that assume uniform seasonal timing miss important local variability. Incorporating fine-scale seasonal information will improve predictions about how climate change affects biodiversity, crop yields and even disease ecology.

Related Arctic Findings

Separate research from October reports communities of non-cyanobacterial diazotrophs (NCDs) living beneath Arctic sea ice. These bacteria can fix nitrogen but do not photosynthesize. While nitrogen-fixation by these microbes in the Arctic has not yet been conclusively demonstrated, edges of sea ice show higher apparent nitrogen-fixation activity. As Arctic ice retreats, expanding NCD populations could boost algal growth, alter marine food webs and change how much CO2 the Arctic Ocean sequesters.

"If algae production increases, the Arctic Ocean will absorb more CO2 because more CO2 will be bound in algae biomass," said Lasse Riemann, a marine microbial ecologist at the University of Copenhagen, who urges that nitrogen fixers be incorporated into future climate models.

The seasonal-timing study and the Arctic microbial findings each underscore how local-scale processes can have global consequences. The seasonality map and related work were published in the journal Nature.