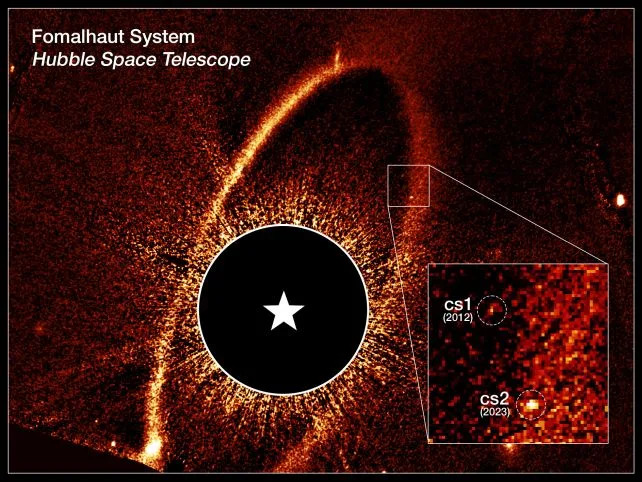

Hubble has imaged a second dust cloud produced by an apparent collision between two ~60 km (37 mi) bodies in the debris disk of the nearby young star Fomalhaut, about 25 light‑years away. The new object, Fomalhaut cs2, resembles an earlier event (cs1, formerly 'Dagon') and implies that large collisions are more frequent in this system than previously expected. From the data, researchers estimate roughly 300 million similar planetesimals orbit the disk. Teams will continue monitoring cs2 with Hubble and JWST to observe changes in shape, brightness and orbit.

Hubble Captures Second Asteroid Smash-Up Around Nearby Star Fomalhaut

For only the second time on record, astronomers have observed the aftermath of an asteroid collision around a star beyond the Solar System. The event was imaged in the debris disk of Fomalhaut, a young star roughly 440 million years old located about 25 light‑years from Earth, making it one of the closest laboratories for studying the early stages of planet formation.

New observations from the Hubble Space Telescope revealed a bright, point‑like source that the research team interprets as a cloud of dust produced when two rocky bodies — each about 60 kilometres (37 miles) across — smashed into one another and were ground to fine debris. The new feature has been labeled Fomalhaut cs2 (circumstellar source 2).

'This is certainly the first time I've ever seen a point of light appear out of nowhere in an exoplanetary system,' says Paul Kalas of the University of California, Berkeley.

Fomalhaut previously produced another puzzling object. In 2004 a bright source was detected and later nicknamed Dagon (originally reported as Fomalhaut b). By 2014 that source had faded, and astronomers concluded it was not a planet but an expanding dust cloud produced by a collision. That earlier cloud is now referred to as Fomalhaut cs1.

When Hubble revisited the system in 2023 it found a second, very similar bright blob at a comparable location in the outer debris ring. The resemblance to cs1 — and the disappearance of the original Dagon signal — led researchers to conclude cs2 is also a collision product rather than a bona fide planet. Jason Wang of Northwestern University summarized the surprise: 'We thought we were reobserving the original source, but careful comparison showed it was a different object.'

By modeling the observed brightness, evolution of cs1, and the debris dynamics, the team estimates the colliding planetesimals were roughly 60 km (37 mi) in diameter. From the frequency of these events and the properties of the debris disk, they infer there may be on the order of 300 million similar bodies orbiting within the Fomalhaut system.

'Earlier theory suggested a collision of this size should occur only once every 100,000 years or more,' Kalas notes. 'Yet in two decades we have seen two such events — implying the outer disk is a far more active environment than expected.'

Mark Wyatt of the University of Cambridge highlights the scientific payoff: 'These observations let us estimate both the sizes of the colliding bodies and how many there are in the disk — information that is otherwise nearly impossible to obtain.'

Why It Matters

The repeated collisions suggest Fomalhaut's outer ring is dynamically active and could represent a stage of planetary system evolution when planetesimals are still colliding and grinding down. High‑resolution imaging has also revealed concentric gaps in the disk, often interpreted as the influence of unseen planets clearing material along their orbits, though no confirmed planets have been directly imaged in those gaps.

Additionally, 2023 observations from the James Webb Space Telescope reported a large knot of dust in the same outer ring where cs1 and cs2 appeared; astronomers suggested that knot may also be a collision signature, though that interpretation remains to be confirmed.

The research team will continue monitoring Fomalhaut with both Hubble and JWST to track cs2's shape, brightness and orbit over time. Kalas notes cs2 could become more elongated or develop a comet‑like appearance as stellar radiation pressure pushes dust grains outward.

The results have been published in the journal Science.

Help us improve.