Researchers have produced the first continuous, multi-spacecraft map of the Sun’s Alfvén surface — the magnetic boundary where the solar wind decouples from the Sun. Combining Parker Solar Probe, Solar Orbiter and three L1 spacecraft, the team tracked how the boundary evolved during the rise of Solar Cycle 25 and found the surface expanded by about 30% as activity increased. The results refine models of solar wind formation, improve space‑weather forecasting, and have implications for magnetic stars and exoplanet environments.

Scientists Release First Continuous Map of the Sun’s Alfvén Surface — Boundary of the Solar Wind Mapped in Detail

Using coordinated measurements from spacecraft spread across the Solar System, researchers have produced the first continuous, multi-spacecraft map of the Sun’s Alfvén surface — the frontier where the Sun’s magnetic influence no longer accelerates or guides the solar wind.

Known as the Alfvén surface, this boundary marks where disturbances in the solar plasma can no longer travel back toward the Sun and the outflowing solar wind becomes magnetically disconnected. The new reconstruction covers the rise of Solar Cycle 25 and reveals how the surface’s shape and height change as solar activity increases.

How the Map Was Built

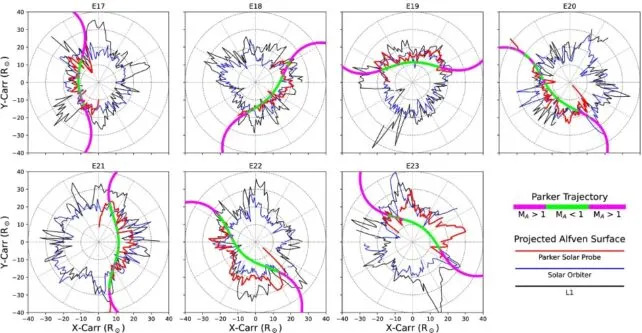

The team combined direct in situ measurements from Parker Solar Probe with complementary observations from Solar Orbiter and three spacecraft near the Earth–Sun L1 Lagrange point. Together these assets provided detailed information on magnetic field, plasma speed, density and temperature across different regions of the inner heliosphere.

Parker Solar Probe, which has repeatedly plunged close to the Sun since 2021, supplied direct samples from below and around the Alfvén surface. Solar Orbiter supplied contextual imaging and off‑Sun measurements, while the L1 spacecraft monitored the solar wind as it propagated past Earth.

Key Findings

The combined six years of observations show that the Alfvén surface is dynamic and structured: as Solar Cycle 25 ramped up, the surface expanded and became more irregular. Overall, the researchers report the Alfvén surface grew by roughly 30% above its median height during the cycle’s rising phase. In most perihelion passes Parker skimmed bulging regions of the boundary, and only during its two deepest dives near solar maximum did it clearly penetrate well below the surface.

“Parker Solar Probe data from deep below the Alfvén surface could help answer big questions about the Sun's corona, like why it's so hot,” says Sam Badman of the Harvard & Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, lead author of the study. “But to answer those questions, we first need to know exactly where the boundary is.”

“This work shows without a doubt that Parker Solar Probe is diving deep with every orbit into the region where the solar wind is born,” says Michael Stevens of CfA. “We are now headed for an exciting period where the probe will witness firsthand how those processes change as the Sun moves through its activity cycle.”

Why This Matters

Mapping the Alfvén surface improves our physical understanding of the solar wind’s origin and the processes that heat the solar corona. These results refine space‑weather models that predict how solar activity affects Earth’s satellites, communications and power grids. They also have implications for other stars: more strongly magnetized stars would likely host larger and more irregular Alfvén boundaries, with consequences for close‑in exoplanets and their habitability.

The research has been published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

Help us improve.