Solar Orbiter observed a medium-class flare on Sept. 30, 2024, and found it was triggered by an avalanche of small magnetic reconnection events that cascaded into a larger eruption. EUI, SPICE, STIX and PHI tracked the cascade from tiny bright points to plasma blobs raining onto the photosphere and X-ray surges, with particles accelerated to ~40–50% of light speed. The finding challenges prior single-event flare models and has implications for space-weather forecasting and stellar flares.

Solar Orbiter Catches a 'Magnetic Avalanche' That Powers Solar Flares

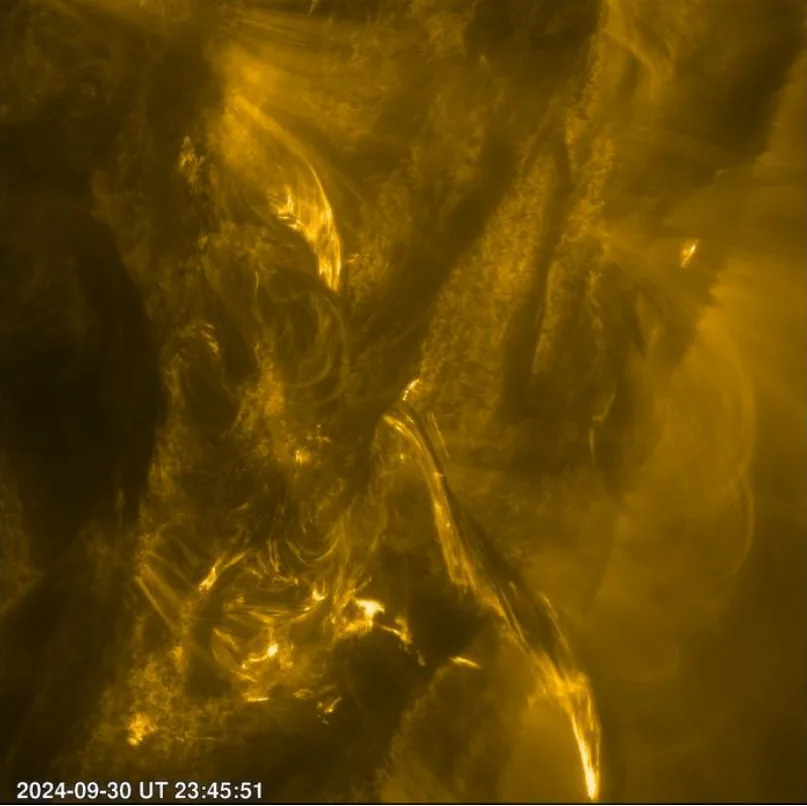

A giant solar flare observed on Sept. 30, 2024, was driven by an avalanche of smaller magnetic disturbances — the clearest evidence yet of how the Sun can release vast amounts of energy in bursts of ultraviolet light and X-rays. The discovery was made by the European Space Agency's Solar Orbiter, which observed the eruption from roughly 27 million miles (43.3 million kilometers) away.

Some solar flares can produce coronal mass ejections (CMEs) — huge plumes of charged plasma hurled into space that, if aimed at Earth, can trigger geomagnetic storms capable of disrupting satellites, power grids and communications while creating spectacular auroras. Understanding how flares are triggered improves space-weather forecasting and helps protect critical infrastructure.

A cascade, not a single spark. Solar Orbiter’s instruments recorded that the medium-class flare began as a series of small, rapidly occurring magnetic reconnection events. These tiny bursts acted like an avalanche, cascading into progressively larger reconnections until a full flare erupted — much like a snow avalanche that starts with a modest slip and grows into a massive slide.

How the spacecraft saw it. The Extreme Ultraviolet Imager (EUI) tracked the event over about 40 minutes, resolving features just a few hundred kilometers across and capturing frames at intervals under two seconds. EUI observed an arching filament of magnetic fields and plasma anchored to a cross-shaped region of intense magnetic activity. Small bright bursts signaled repeated reconnection events that spread rapidly across the region.

Three other Solar Orbiter instruments — SPICE (Spectral Imaging of the Coronal Environment), STIX (an X-ray spectrometer/telescope) and PHI (Polarimetric and Helioseismic Imager) — sampled different layers of the Sun’s atmosphere from the corona down to the visible photosphere. They recorded waves of large plasma blobs energized by magnetic fields, raining down onto the photosphere, and a surge in X-ray emission as the flare peaked.

“Solar Orbiter's observations unveil the central engine of a flare and emphasize the crucial role of an avalanche-like magnetic energy release mechanism at work,” said Miho Janvier, ESA co-project scientist on Solar Orbiter.

At flare peak, charged particles were accelerated to roughly 40–50% of the speed of light, after which the cross-shaped magnetic region relaxed, the plasma cooled, and emissions returned toward normal. The team was surprised that a cascade of smaller reconnection events could accelerate particles to such high energies.

Why this matters. The avalanche model had been proposed previously to explain the statistical behavior of many flares across the Sun, but Solar Orbiter’s observations show it can also drive an individual flare. This challenges existing theories that emphasize a single, dominant reconnection event and raises two urgent questions: are most or all flares produced by similar cascades, and does this mechanism occur on other flaring stars (for example, the more active red dwarfs)?

The Solar Orbiter team’s analysis of the Sept. 30, 2024 flare was published on Jan. 21 in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics. Continued observations will be needed to determine how commonly avalanche-like cascades drive flares and to improve predictive models for space weather.

Help us improve.