Researchers observed two rare, planetesimal-scale collisions in the Fomalhaut system — 25 light‑years away — that produced bright debris clouds initially mistaken for a planet. The impacts, labeled Fomalhaut cs1 and cs2, likely involved bodies about 37 miles (≈60 km) across and occurred within a 20‑year span around a 440‑million‑year‑old star. Models suggest the system contains roughly 1.8 Earth masses in large planetesimals and another 1.8 Earth masses in smaller fragments; there is about a 10% chance the paired impacts were guided by an unseen planet. These events underline challenges for direct imaging of exoplanets and refine models of planetary-system evolution.

Two Planet-Scale Collisions Spotted Near the 'Eye of Sauron' Star — 25 Light-Years Away

A team of astronomers has observed an extraordinarily rare phenomenon in the nearby Fomalhaut system: not one but two massive collisions between large rocky bodies, producing bright, expanding clouds of debris that briefly mimicked the appearance of an exoplanet.

What Was Observed

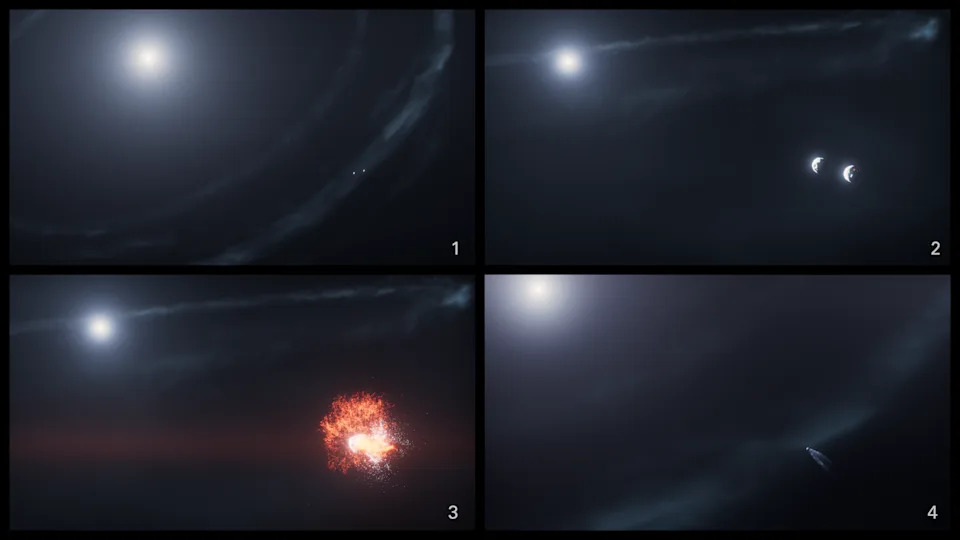

Over the past two decades researchers detected two separate impact events, now labeled Fomalhaut cs1 and Fomalhaut cs2, around Fomalhaut — a star roughly 25 light-years from Earth in the constellation Piscis Austrinus. The collisions involved planetesimals (the rocky building blocks of planets) that smashed together and created luminous, expanding debris clouds visible in direct imaging.

Why Fomalhaut Is Special

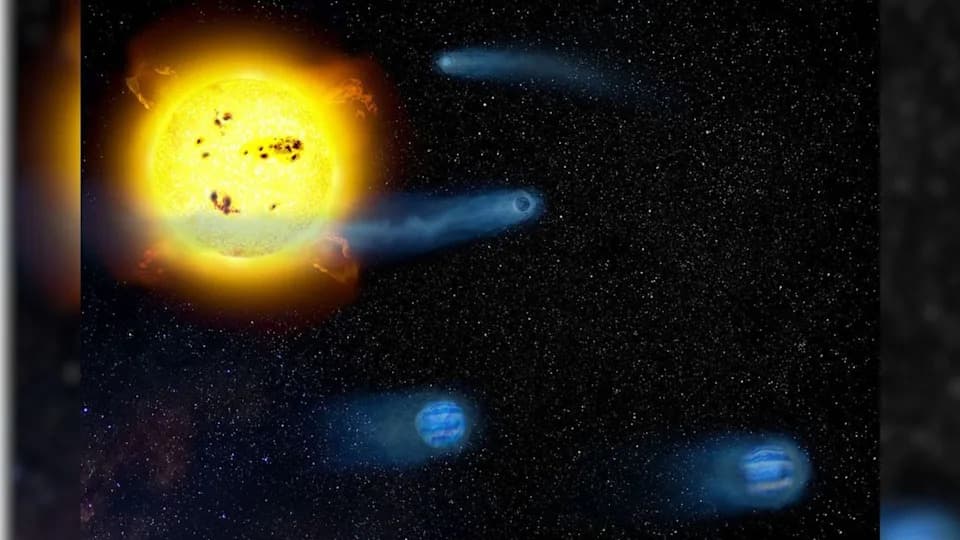

Fomalhaut is famous for a prominent debris belt at about 133 astronomical units (AU) from the star (1 AU ≈ 93 million miles or 150 million kilometers). That ring gives the system a distinctive "Eye of Sauron" look and is thought to be a denser analog of the chaotic, collision-rich environment of our own solar system more than four billion years ago.

Reconstructing the Impacts

By modeling the debris mass and grain sizes, the team infers the colliding bodies were roughly 37 miles (≈60 kilometers) across — about four to six times the diameter of the asteroid widely associated with the mass extinction of non-avian dinosaurs 66 million years ago. Theory predicts collisions of this scale are extremely rare (on the order of one every ~100,000 years), so seeing two in ~20 years was a surprising coincidence.

“Fomalhaut cs2 looks exactly like an extrasolar planet reflecting starlight,” said Paul Kalas of UC Berkeley, lead author of the study. Co-author Jason Wang of Northwestern added, “These larger bodies are like the larger bodies that comprise our own asteroid and Kuiper belts.”

System Inventory and Long-Term Implications

From their models the researchers estimate the Fomalhaut system contains about 1.8 Earth masses in large primordial planetesimals (a population that could number on the order of 300 million objects) plus another 1.8 Earth masses in much smaller fragments under 0.186 miles (0.3 km). Those small fragments continuously replenish the finest dust grains — many only a few ten-thousandths of an inch (a few micrometers) across — that give the belt its shimmering appearance. Without this reservoir, radiation pressure and stellar wind would quickly disperse the dust.

Extrapolating collision rates over the system’s estimated age of about 440 million years, the study suggests roughly 22 million similar collisions could have occurred during Fomalhaut’s lifetime.

Is There an Unseen Planet?

Although the transient debris clouds are not planets themselves, the researchers estimate roughly a 10% probability that the two impacts are not purely random. Their proximity in time and location could indicate the gravitational influence of an unseen planet shepherding planetesimals into collision-prone regions.

Why This Matters for Planet Hunters

The findings carry important practical implications: transient debris clouds can closely resemble exoplanets in direct images. This complicates searches for real planets and will be relevant for next-generation direct-imaging missions, including NASA’s planned Habitable Worlds Observatory, which aims to image habitable-zone planets around nearby stars.

By refining estimates of collision rates, debris masses and grain properties, the study improves our understanding of planet formation and debris-disk dynamics and helps astronomers distinguish true planets from ephemeral, glittering collision remnants.

Help us improve.