A candidate rocky exoplanet, HD 137010b, has been identified about 146 light‑years away around a K‑type dwarf. The object—detected as a single ten‑hour transit in Kepler K2 data—appears to be ~1.06× Earth in diameter with an uncertain ~355‑day orbit and receives ~29% of Earth's stellar flux. The host star's brightness (mag 10) makes atmospheric follow‑up with instruments like JWST or future missions such as PLATO feasible; additional transits are needed to confirm the planet and determine if a thick CO₂ atmosphere could keep it warm.

Candidate 'Cold Earth' HD 137010b — A Rocky World on the Edge of Habitability 146 Light‑Years Away

A possible rocky exoplanet, catalogued as HD 137010b, has been identified about 146 light‑years from Earth and may orbit at the outer edge of its star's habitable zone. The detection is preliminary: the object is a candidate planet based on a single observed transit, and further observations are needed to confirm its existence and characterize its environment.

Discovery And Basic Properties

A team led by Alexander Venner at the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy discovered the candidate while re‑examining archival data from the Kepler Space Telescope's K2 mission. The host is a K‑type dwarf, slightly smaller, cooler and dimmer than the Sun. Current estimates place the planet's diameter at about 1.06 times Earth and suggest an orbital period near 355 days, though those values carry substantial uncertainty because only a single transit was measured.

How Much Light Does It Get?

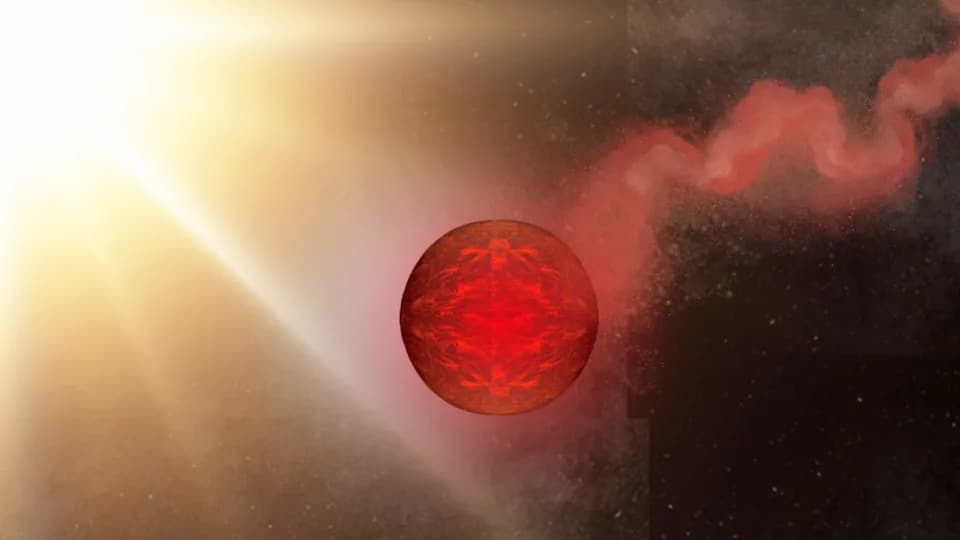

HD 137010b would receive roughly 29% of the stellar flux−90 °F (−68 °C), slightly colder than the average temperature on Mars (≈ −85 °F / −65 °C). A much thicker CO₂‑rich atmosphere, however, could trap enough heat to make the surface warmer and potentially hospitable in regions.

Observations, False Positives, And Next Steps

Venner's team detected a single ten‑hour transit and used recent and historical imaging plus other observatory data to rule out common false positives such as stellar variability or background eclipsing binaries. Normally, two or three transits are required to confirm a planet, so HD 137010b remains a candidate until additional transits or radial‑velocity signals are observed.

Why The Host Star's Brightness Helps

The host star is relatively bright at magnitude 10, an outlier among Kepler targets (many of which are fainter than magnitude 13). This brightness makes the system accessible to professional spectrographs and to powerful space telescopes like JWST for atmospheric follow‑up, and even visible with modest amateur equipment (≈150 mm/6‑inch telescopes) under good conditions.

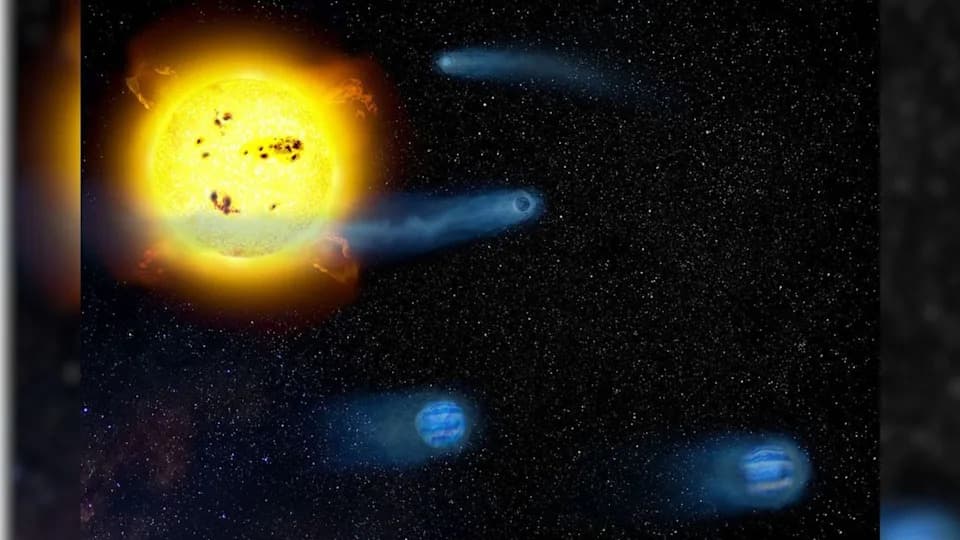

Atmospheric probes—transmission spectroscopy during transit and eclipse measurements when the planet passes behind the star—rely on a bright host to produce a detectable signal. That is why this system is particularly attractive for follow‑up despite the single transit.

Challenges And Upcoming Opportunities

The long, roughly 355‑day period means transits are infrequent and, because the period isn't precisely known, predicting the next transit window is difficult. If NASA's TESS or ESA's CHEOPS fail to catch another transit, ESA's PLATO mission (scheduled for launch in December 2026) offers a strong chance of detecting further transits and refining the orbital period and planet parameters.

Habitable Zone Probabilities

Venner's team estimates a 40% probability that HD 137010b lies within the "conservative" habitable zone and a 51% probability that it falls within an "optimistic" habitable zone definition. There remains roughly a 50/50 chance it does not lie in the habitable zone at all. These probabilities reflect current parameter uncertainties and differing definitions of habitability.

For now, HD 137010b is a compelling "maybe" — a candidate that could be a frozen rock or, with the right atmosphere, a much more temperate world. The discovery and analysis were reported in a paper published Jan. 27 in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

Help us improve.