High-precision astrometry with the GRAVITY instrument on the VLT reveals a nine-month wobble in the gas giant HD 206893 B, located about 133 light-years away. The team infers a companion orbiting the planet at roughly 0.2 AU with an inclination near 60°, and estimates a mass of approximately 0.4 Jupiter masses (about 7–8× Neptune). If confirmed, this object would be far more massive than any Solar System moon and could force a rethink of how we define moons.

Wobble in Distant Gas Giant Points to a Colossal Exomoon — Big Enough To Rethink 'Moon'

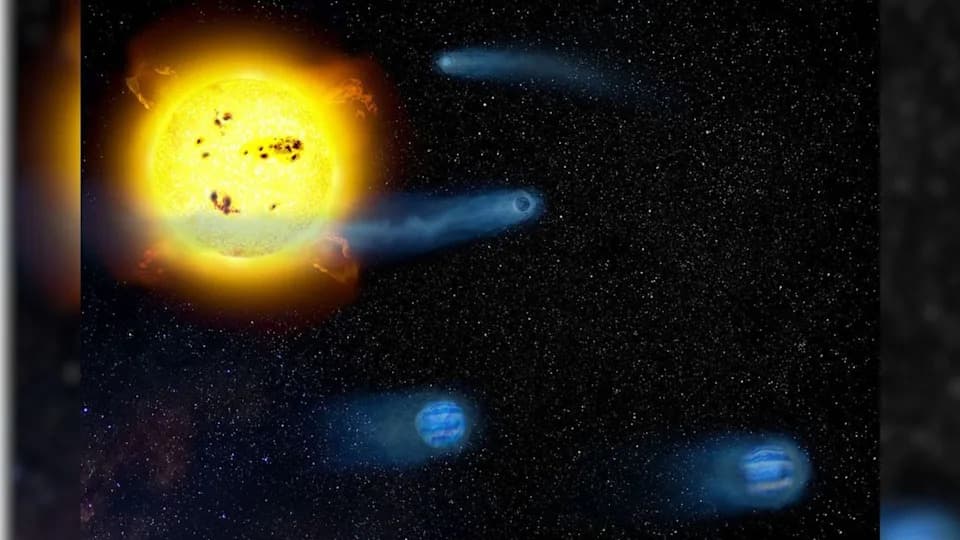

A gas-giant companion about 133 light-years away shows a subtle, regular wobble that astronomers say could be caused by an enormous exomoon — so large it may challenge our conventional definition of a moon.

The system: The object under study is HD 206893 B, a substellar companion roughly 28 times the mass of Jupiter orbiting a young star. Observations with the GRAVITY instrument on the European Southern Observatory's Very Large Telescope (VLT) in Chile revealed a small periodic deviation superimposed on the companion's expected orbital motion.

How the signal was found

The team used high-precision astrometry — repeated, accurate measurements of the object's position on the sky — to detect tiny departures from a simple Keplerian orbit. GRAVITY's sensitivity enabled monitoring on timescales from days to months rather than the multi-year baselines typically used for massive, slow-moving objects.

“What we found is that HD 206893 B doesn't just follow a smooth orbit around its star. On top of that motion, it shows a small but measurable back-and-forth 'wobble',” said Quentin Kral of the University of Cambridge. “The wobble has a period of about nine months and an amplitude comparable to the Earth–Moon separation. This is the kind of signal you expect from a massive unseen companion.”

What the wobble implies

From the observed motion the authors infer a companion orbiting HD 206893 B roughly once every nine months, with a separation on the order of 0.2 astronomical units (about one-fifth the Earth–Sun distance). The putative moon's orbit appears inclined by roughly 60° relative to the planet's orbital plane, which could reflect past dynamical interactions in the system.

Mass and classification: The inferred companion would be extraordinarily massive for a moon — the team estimates roughly 0.4 Jupiter masses (≈40% of Jupiter), which corresponds to about 7–8 times the mass of Neptune. Even at the lower end of this range, the object would be thousands of times more massive than the largest moon in our Solar System, Ganymede. At these masses the boundary between a very low-mass binary companion and a true moon becomes blurred, and there is no universally accepted definition of an "exomoon."

Caveats and next steps

Claims of exomoon detections have historically been controversial. The authors stress that while the astrometric signal is compelling, independent confirmation is required. The result is available as a pre-peer-reviewed manuscript on arXiv and has reportedly been accepted for publication in Astronomy & Astrophysics.

Astrometry is especially well suited to finding longer-period moons around wide-orbit planets or substellar companions — precisely the parameter space where massive moons are most likely to be stable. The team suggests that their method could provide a roadmap for future exomoon searches.

Implications: If confirmed, this discovery would push astronomers to refine how they classify satellites versus low-mass companions, and it would reveal that nature can assemble moon-sized bodies far larger than anything in our Solar System. Future observations with high-precision instruments will be crucial to verify the candidate and to map the system in greater detail.

Help us improve.