The V1298 Tau system — a 23-million-year-old Sun-like star about 350 light-years away — hosts four large, low-density planets that are actively losing their atmospheres. Using transit timing variations, astronomers measured the planets' masses and found them to be "puffy" and undergoing photoevaporation driven by X-ray and EUV radiation. Models predict the inner pair will likely become rocky super-Earths while the outer pair may retain some gas as mini-Neptunes. The study, published Jan. 7 in Nature, provides a direct snapshot of how common exoplanets may form.

How Stellar Radiation Carves Super-Earths: Young V1298 Tau Planets Seen Evaporating

New observations of a young, Sun-like star show four bloated planets actively losing their atmospheres — offering a direct glimpse of how the galaxy's most common planets, super-Earths and sub-Neptunes, can form.

Young System, Big Planets

About 350 light-years away, the V1298 Tau system hosts a roughly 23-million-year-old star orbited by four compact, transiting planets. Discovered in 2019 using data from NASA's Kepler/K2 mission, the worlds have unusually large radii — roughly 5–10 times that of Earth — and orbital periods of 8.2, 12.4, 24.1 and 48.7 days. All four orbits lie well inside Mercury's orbit in our solar system.

Weighing The Planets With TTVs

A team led by John Livingston at the Astrobiology Center in Tokyo (with collaborators Erik Petigura and Trevor David) used transit timing variations (TTVs) to measure the planets' masses. In tightly packed systems, mutual gravitational tugs make transits arrive slightly early or late; the magnitude of those timing shifts reveals each planet's mass. Combining measured masses with transit-derived radii gives the planets' densities.

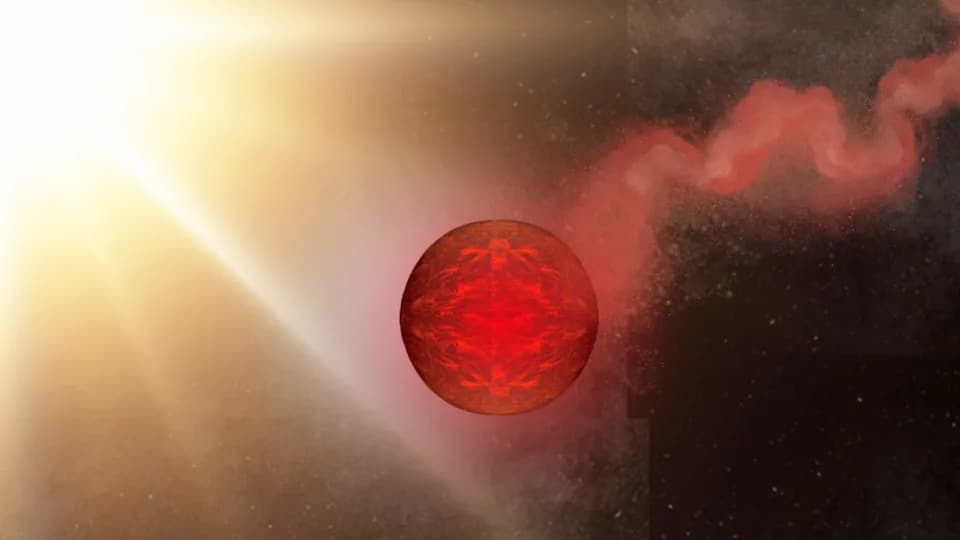

Puffy Worlds Losing Their Gas

The TTV-based masses show that these planets are extremely low density — “puffy” worlds with extended atmospheres. Intense extreme-ultraviolet (EUV) and X-ray radiation from the young star is heating and inflating those envelopes. Once inflated, the atmospheres are only weakly bound and are being stripped away by radiation-driven outflows in a process known as photoevaporation. The team searched for spectral signatures of escaping gas but found those planetary signals masked by the star's strong stellar wind.

"By weighing these planets for the first time, we have provided the first observational proof. They are indeed exceptionally puffy," Trevor David said, underscoring the result's importance as a benchmark for planet-evolution theories.

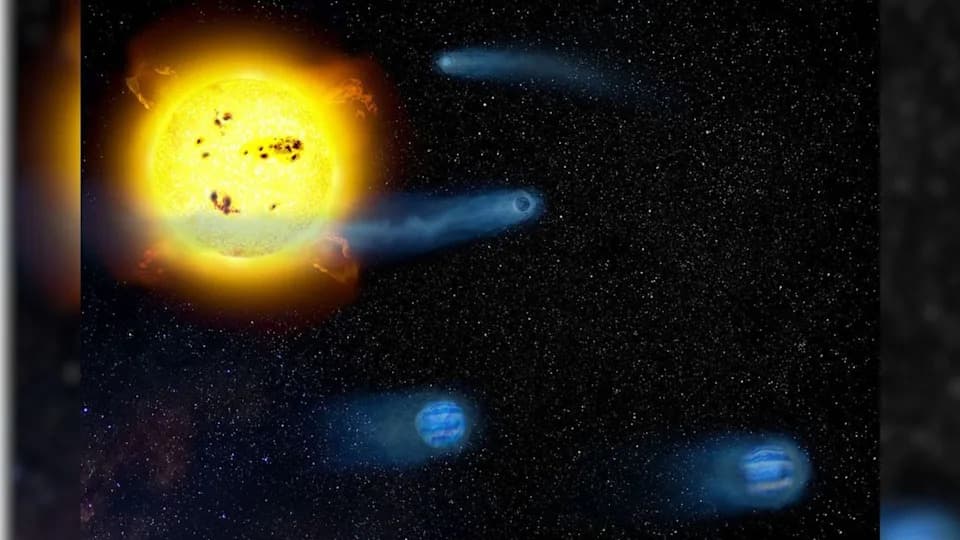

What Happens Next — Super-Earths and Mini-Neptunes

Models indicate photoevaporation will continue for roughly another 100 million years. The data imply all four planets share similarly sized rocky cores. The two innermost planets are likely to lose their atmospheres completely and become rocky super-Earths. The outer two are currently about twice as massive, giving them stronger gravity and partial protection; they may retain some gas and evolve into mini-Neptunes, or eventually be stripped down as well.

Broader Implications

Because super-Earths and sub-Neptunes are among the most commonly discovered exoplanets, observing this evaporation in real time gives astronomers a clear, early-stage picture of how those planets form and evolve. The compact, regularly spaced architecture of V1298 Tau resembles "peas-in-a-pod" systems such as TRAPPIST-1, suggesting a common evolutionary pathway from puffy, gas-rich beginnings to the dominant planet types we detect across the galaxy.

Publication: The full findings were published Jan. 7 in the journal Nature.

Help us improve.