New analysis of Juno’s 2022 flyby data indicates Europa’s ice shell averages about 18 miles (≈29 km) thick in the observed region — a more precise local measurement than previous, widely varying estimates. The team also detected signs of subsurface cracks, pores or other scatterers extending hundreds of metres, but those features are likely narrow and inefficient for transporting large amounts of oxygen and nutrients. Upcoming missions — NASA’s Europa Clipper (arriving 2030) and ESA’s JUICE (arriving 2031) — will provide higher-resolution data to better assess Europa’s habitability.

Juno Finds Europa’s Ice Shell Averages About 18 Miles Thick — Big Implications for Habitability

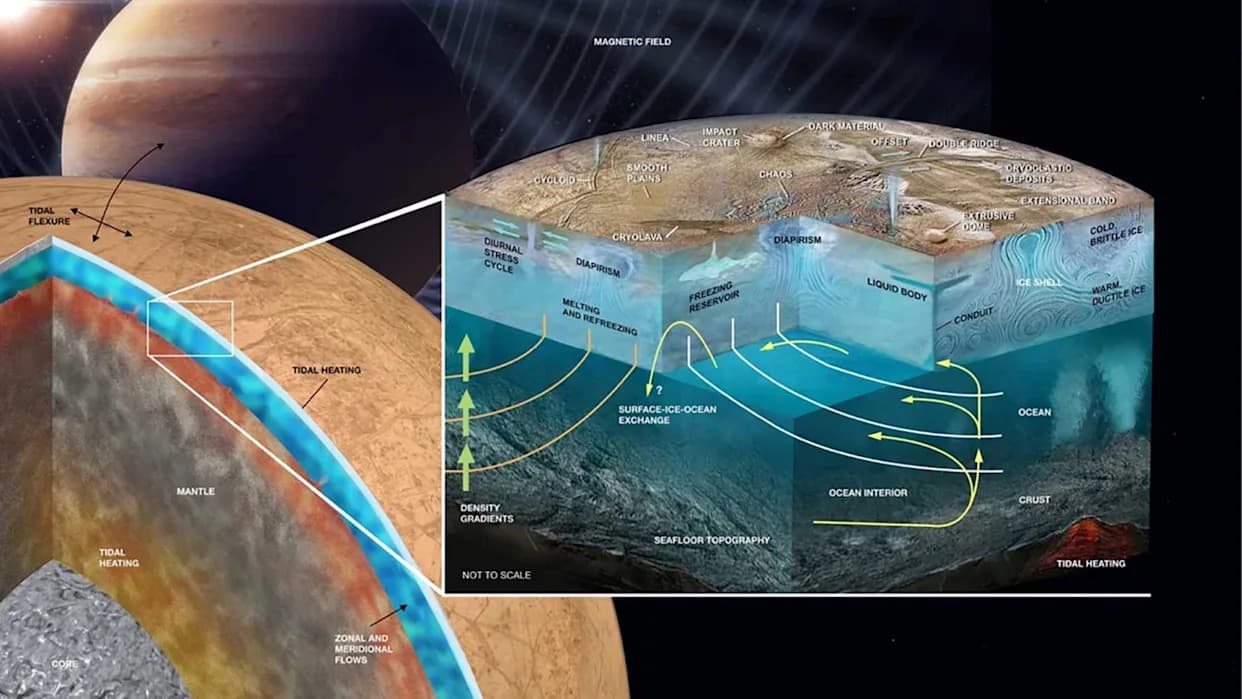

Jupiter’s icy moon Europa has long been a top target in the search for life beyond Earth because a global, salty ocean likely lies beneath its frozen surface. New analysis of data from NASA’s Juno spacecraft — which performed a close flyby of Europa in 2022 — indicates the ice shell over the region Juno observed averages roughly 18 miles (about 29 kilometers) thick.

What the Measurement Means

This is the first time scientists have been able to narrow the estimate to a specific thickness for a particular region; earlier estimates ranged widely from roughly 0.5 miles (≈0.8 km) to tens of miles. A thick ice shell increases the distance that oxidants and nutrients must travel to reach the subsurface ocean, complicating scenarios for biological exchange between surface and ocean.

How the Team Reached This Result

Researchers at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory used data from Juno’s microwave radiometer to probe the structure of Europa’s near-surface ice. The observations are consistent with an average shell thickness near 18 miles for the area studied. The team published their findings in a paper in Nature Astronomy.

"If an inner, slightly warmer convective layer also exists, which is possible, the total ice shell thickness would be even greater," said Steve Levin, Juno project scientist and coauthor of the paper. He noted that modest amounts of dissolved salt in the ice — suggested by some models — could reduce the effective thickness by roughly three miles (≈5 km).

Fractures, Pores, and Pathways

The Juno data also show evidence for subsurface scatterers — interpreted as cracks, pores, or other heterogeneities — extending to depths of hundreds of metres below the surface. The team suggests these features could be only a few inches (a few centimeters) across yet extend hundreds of feet (tens to a few hundred meters) downward.

While such narrow fractures could provide limited pathways for surface oxidants and nutrients to migrate inward, the authors caution they are probably inefficient conduits for the large-scale transport life would require.

Why This Matters

Determining ice thickness and the presence or absence of connected pathways between the surface and ocean are key to assessing Europa’s habitability. A thicker shell or poorly connected fractures would make it harder for surface chemistry to influence the ocean environment where life might exist.

What’s Next

More detailed observations are coming: NASA’s Europa Clipper is scheduled to arrive at Jupiter in 2030 and will perform nearly 50 flybys of Europa, and the European Space Agency’s JUICE (JUpiter ICy moons Explorer) is expected to arrive in 2031. Those missions should better map the ice shell, look for active exchange processes, and refine estimates of how material might move between surface and ocean.

Bottom line: Juno’s measurements strengthen the case that Europa’s ice shell can be tens of kilometers thick in places, and although subsurface fractures may exist, they may not provide easy routes for the oxygen and nutrients needed to support life in the ocean below.

Help us improve.