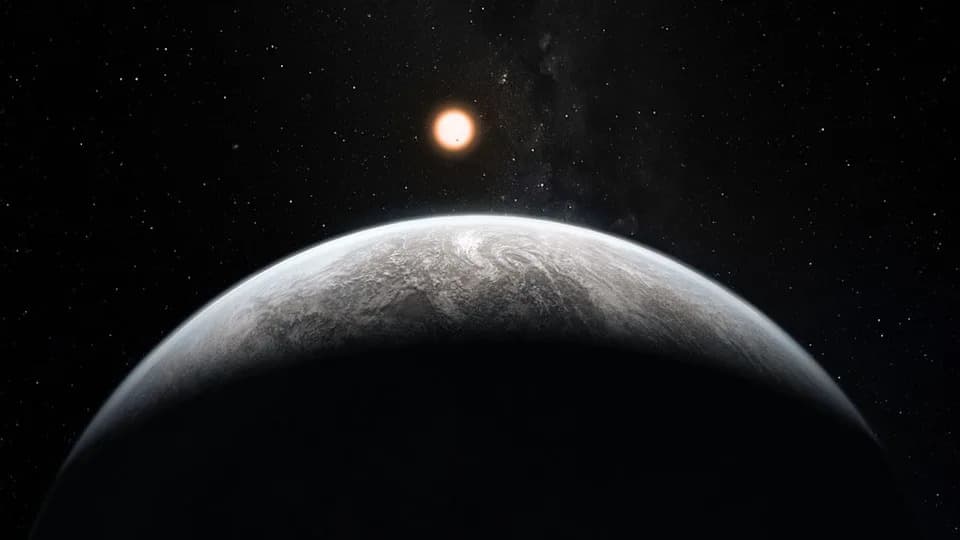

New simulations show Earth’s magnetosphere can act as both a shield and a conduit, guiding atmospheric particles down the magnetotail and onto the Moon. This mechanism provides a plausible explanation for excess volatiles found in Apollo 17 regolith without requiring an early unmagnetized Earth. Surprisingly, models suggest modern Earth’s stronger magnetic field transfers more material to the Moon than a weaker ancient field. The result affects prospects for lunar resources and improves our understanding of planetary atmospheric loss, including Mars.

Earth’s Magnetic Field: Shield — and a Hidden Pathway to the Moon

New simulations suggest Earth’s magnetic field—long portrayed as a protective shield—can also act as a conduit that funnels atmospheric particles into space and onto the Moon. That unexpected pathway helps explain excess volatiles found in Apollo 17 lunar soil and changes how we think about planetary atmospheric escape.

Volatiles on the Moon That Didn’t Come From the Sun

When Apollo missions returned samples of lunar regolith, scientists discovered volatile compounds (including water, carbon dioxide and noble gases such as helium, argon and nitrogen) that were not seen in the mission’s rock samples. While the solar wind implants charged particles into the Moon’s exposed surface, the amounts measured in Apollo 17 samples were larger than solar contributions alone could explain.

Two Competing Explanations

In 2005, researchers at the University of Tokyo proposed that some of those volatiles originated in Earth’s atmosphere during an early epoch when Earth’s magnetic field was weak or absent. In that scenario, atmospheric molecules could escape more readily from an unshielded planet and later reach the Moon.

Now a team led by astrophysicist Shubhonkar Paramanick of the University of Rochester offers an alternative (and surprising) mechanism: under modern conditions the magnetosphere itself can guide atmospheric material into space, where the solar wind carries it to the Moon (Paramanick et al., Nature Communications Earth & Environment).

How the Magnetotail Funnels Atmosphere

Earth’s magnetotail—the elongated nightside extension of the magnetosphere formed by the solar wind—contains two lobes of oppositely directed magnetic field lines separated by a plasma sheet. Turbulence, unstable plasma and magnetic reconnection in this region can free atmospheric particles, allowing them to travel along field lines down the tail. When the Moon passes through Earth’s magnetotail on its nightside, many of these particles can be deposited and trapped in regolith grains.

“Atmospheric transfer is efficient only when the Moon is within Earth’s magnetotail,” Paramanick and colleagues write. They argue that ongoing implantation during Earth’s long-lived geodynamo better explains the non-solar contributions in lunar soil than a brief, early unmagnetized epoch.

Simulations and Surprising Results

The Rochester team simulated particle escape from an ancient Earth (weaker field, stronger early solar wind) and from modern Earth (stronger field, weaker solar wind). Counterintuitively, the models show that the modern configuration transfers more atmospheric material to the Moon than the ancient one. That implies the lunar surface may contain more terrestrial-derived volatiles than previously estimated.

Why This Matters

These findings have multiple implications:

- Scientific: The Moon’s regolith could preserve a long-term record of Earth’s early atmosphere tied to the geodynamo’s history.

- Practical: Volatiles trapped in regolith—water and oxygen-bearing molecules—could become in-situ resources for future lunar missions, reducing resupply needs from Earth.

- Comparative Planetology: Understanding how Earth sheds particles via magnetic processes helps refine models for atmospheric loss on planets like Mars, which likely lost its thick early atmosphere after its dynamo stopped.

Conclusion

Paramanick’s work reframes the magnetosphere not only as a shield but also as a dynamic participant in atmospheric exchange. The magnetotail may have been a persistent, efficient pathway delivering terrestrial molecules to the Moon throughout much of Earth’s 3.7-billion-year geodynamo history, offering a plausible explanation for the non-solar isotope signatures observed in lunar soils.

Reference: Paramanick et al., Nature Communications Earth & Environment (study on magnetotail-driven transfer of atmospheric particles to the Moon).

Help us improve.