New laboratory experiments and planetary models show that iron‑rich molten layers (basal magma oceans) inside some super‑Earths can become metallic and electrically conductive under extreme pressure. Planets about 3–6 times Earth's mass could sustain BMO‑driven magnetic dynamos for billions of years, producing surface fields that may rival or exceed Earth's. These long‑lived magnetic shields would help protect atmospheres and improve habitability prospects, and might be detectable with future observations.

Super‑Earths May Forge Magnetic Shields From Deep Molten Layers, Boosting Habitability

New research suggests many "Super‑Earth" exoplanets — rocky worlds larger than Earth but smaller than Neptune — could generate long‑lived magnetic fields from molten rock layers sandwiched between their core and mantle. Such magnetic shields would help protect atmospheres and surfaces from harmful stellar and cosmic radiation, improving these planets' prospects for habitability.

How a Magma Layer Could Power a Planetary Dynamo

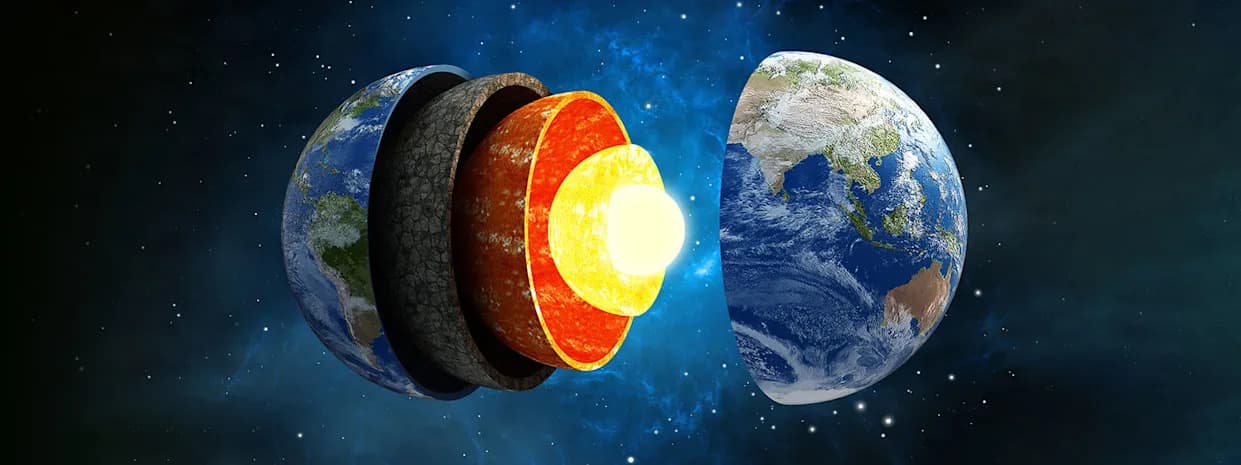

On Earth, the global magnetic field is produced by motions of liquid iron in the outer core around a solid inner core. That core dynamo depends on heat and compositional buoyancy supplied by the growing inner core. Many larger rocky planets, though, may have cores that are fully solid or fully liquid — configurations that can limit an Earth‑like dynamo.

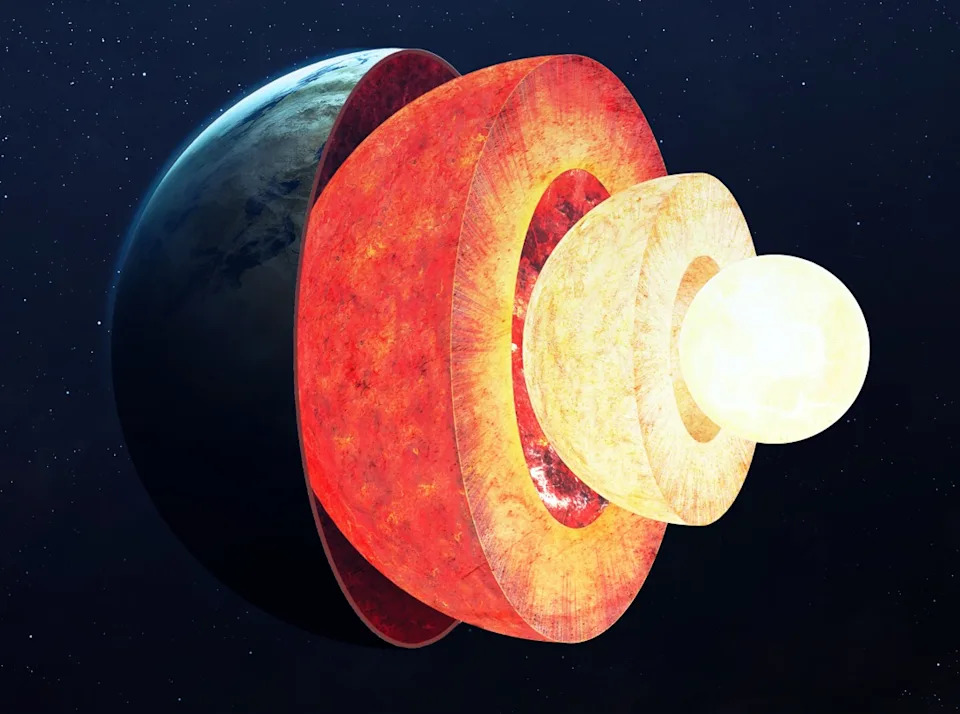

The new study, published Jan. 15 in Nature Astronomy, explores an alternative: a basal magma ocean (BMO), a molten, iron‑rich layer that forms at the base of the mantle above the core. The researchers propose that repeated giant impacts during planet formation can concentrate iron‑rich melt at depth, producing a persistent BMO that — under extreme pressure — becomes electrically conductive and can drive its own dynamo.

"A strong magnetic field is very important for life on a planet," said Miki Nakajima, lead author and associate professor of Earth and environmental sciences at the University of Rochester. "Super‑Earths can produce dynamos in their core and/or magma, which can increase their planetary habitability."

Laboratory Tests And Planet Models

To test this idea, Nakajima and colleagues performed shock‑compression experiments that subjected rock‑forming materials to pressures comparable to those in planets several times Earth's mass. The experiments showed that iron‑rich magma can metallize — that is, become electrically conductive — under such crushing pressures. When these laboratory results were combined with planetary interior models, the team found that super‑Earths roughly 3–6 times Earth's mass could sustain BMO‑driven dynamos for billions of years.

In some model scenarios, the resulting surface magnetic field could rival or even exceed Earth's. The team notes that BMO dynamos might last longer than conventional core dynamos in certain super‑Earths because higher pressures and different thermal evolution can preserve molten deep layers for extended periods.

As Luca Maltagliati, senior editor at Nature Astronomy, observed, "Planets with masses 3–6 times that of Earth might have their main magnetic field engine not in the core like the Earth but in a layer between the core and mantle."

Implications And Observational Prospects

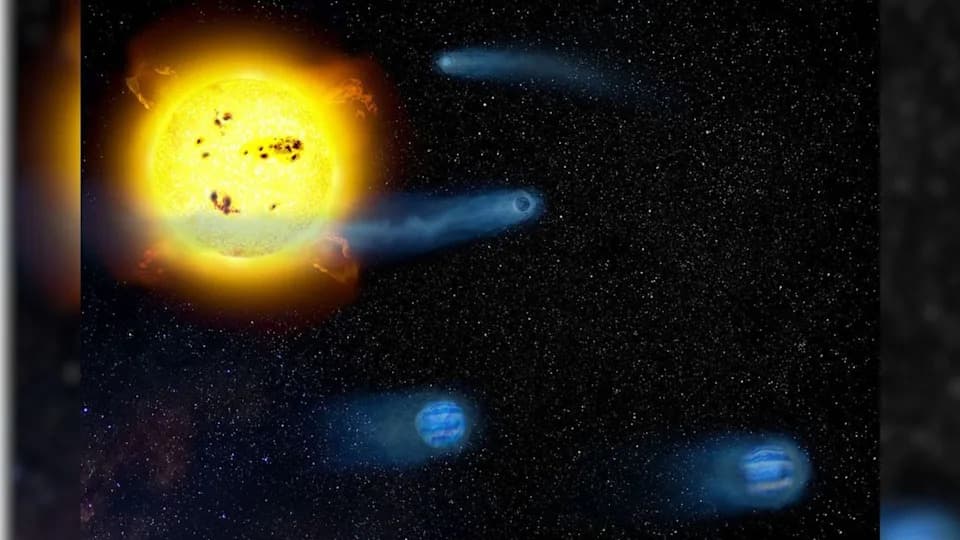

Long‑lived magnetic shields help prevent atmospheric erosion by stellar winds and protect planetary surfaces from energetic particles — factors widely regarded as important for long‑term habitability. Although directly detecting exoplanet magnetic fields remains challenging with current instruments, the authors suggest that particularly strong BMO‑driven dynamos could produce observable signatures in the future (for example, auroral emissions or interactions with a host star's wind).

Overall, the study expands the range of interior structures that might support magnetic protection on rocky exoplanets and highlights that many super‑Earths could be more hospitable than previously thought.

Help us improve.