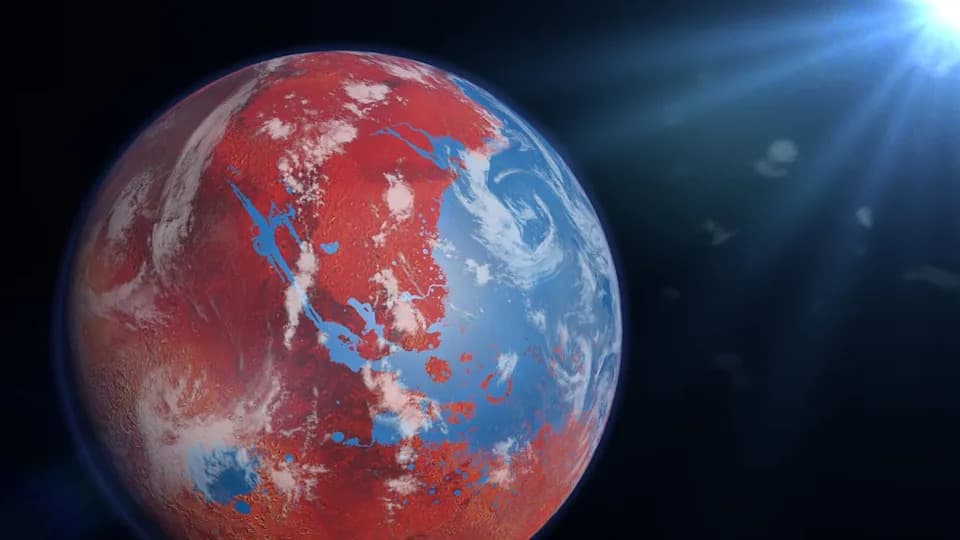

New simulations by Stephen Kane (UC Riverside) indicate Mars helped shape Earth’s long-term climate by influencing Milankovitch orbital cycles. Removing Mars from orbital models made two key cycles vanish, despite Mars being only about a tenth of Earth’s mass. The result suggests outer planets can have a large impact on a habitable world's climate and has implications for both human evolution and exoplanet habitability.

Tiny Mars, Huge Consequences: How Mars Shaped Earth's Climate — And Our Evolution

Millions of years ago, an Ice Age began that altered the course of life on Earth. Changes in ocean circulation made the Horn of Africa markedly drier, thinning dense forests into isolated pockets within expanding savannas. Tree-dwelling primates that once remained aloft were forced into tall grasses, where they faced greater risks from predators.

For one lineage of primates, that shifting environment became both a threat and an opportunity. Over millions of years they adapted to open landscapes by walking upright, which freed their hands for infant care and later for manipulating objects and tools. Those primates are our ancestors — and new research suggests that Mars may have played an unexpected role in triggering the climatic changes that helped set this evolutionary path.

How a Small Planet Makes a Big Difference

Ice Ages and long-term climate cycles are driven in part by regular variations in Earth’s orbit, axial tilt, and precession. Known as Milankovitch cycles, these orbital patterns are shaped by the gravitational pulls of other planets and determine how solar energy is distributed across Earth over tens of thousands to millions of years.

Stephen Kane, a planetary scientist at the University of California, Riverside, tested Mars’s influence using computer simulations of Earth’s orbit spanning tens of millions of years. When Mars was removed from the models, the longest Milankovitch cycle persisted, but two other important cycles disappeared entirely. In other words, Mars — only about a tenth of Earth’s mass — exerts an outsized effect on Earth’s long-term climate variability.

“I knew Mars had some effect on Earth, but I assumed it was tiny,” Kane said. “Because Mars is farther from the sun, it has a larger gravitational effect on Earth than it would if it were closer. It punches above its weight.”

Implications for Life Here and Elsewhere

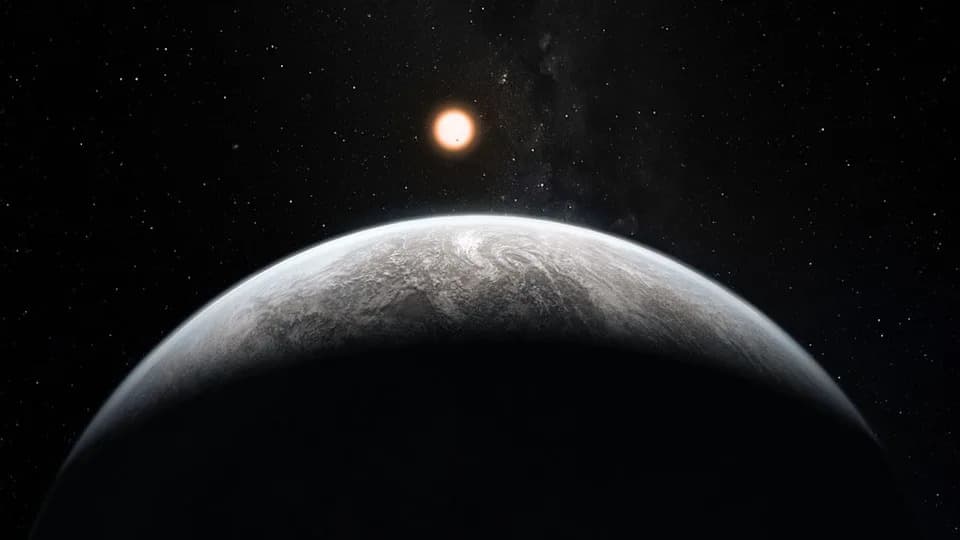

Kane’s findings matter beyond our solar system. Planets farther out in other systems could similarly influence the orbital cycles and climate stability of Earth-sized worlds in the habitable zone. Periodic variations in eccentricity and insolation could amplify ocean temperature gradients and circulation, potentially enhancing processes that recycle and redistribute organic material—factors that might affect planetary habitability.

The research also invites a striking thought: a small, seemingly barren world like Mars may have helped shape the environmental pressures that influenced human evolution. Without Mars’s gravitational contribution, Earth’s orbital rhythms — and the climate cycles they drive — would be different. What would life on Earth, including our own ancestors, have looked like without those rhythms?

Publication: The study appears in the Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific.

Originally featured on Nautilus.

Help us improve.