The University of Tokyo team used time-delay cosmography — timing delays between multiple lensed quasar images — to infer the Hubble constant. Their result aligns with higher local measurements (~45 miles/sec/Mpc) rather than the lower early-universe estimate (~42 miles/sec/Mpc), reinforcing the so-called Hubble tension. Current precision is ~4.5%; the team says ~1–2% precision will be required to decisively resolve whether the discrepancy reflects new physics.

A Speed Camera for the Universe — Time-Delay Cosmography Supports a Higher Hubble Value

A Speed Camera for the Universe

The universe is vast — and it grows larger every instant. That expansion is not uniform: the farther an object lies from us, the faster it appears to recede. Astronomers quantify that recession with Hubble's constant, which indicates how much recessional velocity increases per unit distance. For every megaparsec (about 3.3 million light-years), the apparent speed increases by roughly 45 miles per second, a relationship first identified by Edwin Hubble in 1929.

New Technique: Time-Delay Cosmography

Researchers at the University of Tokyo have introduced an independent method called time-delay cosmography to refine measurements of Hubble's constant, publishing their results in Astronomy & Astrophysics. Unlike traditional "distance ladder" approaches, this technique exploits gravitational lensing to measure cosmic distances directly.

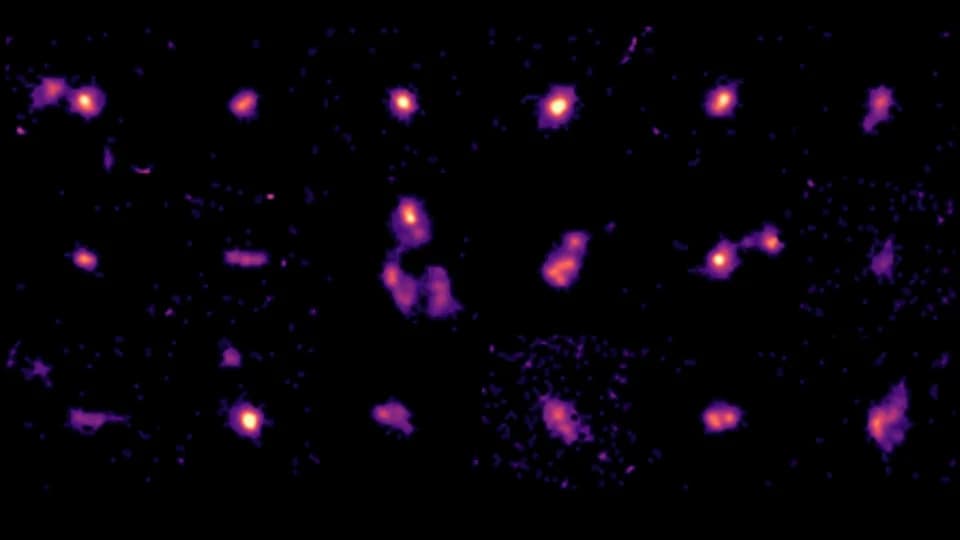

A massive foreground galaxy can bend and split the light of a bright background object such as a quasar, producing multiple images. Because the light for each image travels along a different path, intrinsic brightness changes in the quasar appear at staggered times. By precisely measuring those time delays and modeling the lensing galaxy's mass, astronomers can infer absolute distances and, from them, the expansion rate of the universe.

Results And The Hubble Tension

Applying time-delay cosmography, the University of Tokyo team derived a value for the Hubble constant that aligns with the higher, locally determined measurements — roughly 45 miles per second per megaparsec — rather than the lower value inferred from observations of the early universe (near 42 miles/sec/Mpc). This discrepancy between local and early-universe measurements is known as the Hubble tension and has sparked debate about whether it arises from measurement systematics or from new physics.

"Our measurement of the Hubble constant is more consistent with other current-day observations and less consistent with early-universe measurements," said Kenneth Wong, co-author and astronomer at the University of Tokyo. "This is evidence that the Hubble tension may indeed arise from real physics and not just some unknown source of error in the various methods."

The team emphasized that their method still requires refinement. Their present precision is about 4.5 percent; they estimate that a precision of roughly 1–2 percent would be needed "to really nail down the Hubble constant to a level that would definitively confirm the Hubble tension," said co-author Eric Paic, also at the University of Tokyo.

Why This Matters

Time-delay cosmography provides an independent and complementary way to measure cosmic expansion, reducing reliance on multi-step distance ladders and offering a direct probe that links geometry, gravity, and cosmic history. If further improvements confirm the higher local value with percent-level precision, it would strengthen the case that the Hubble tension points to new physics beyond our current cosmological model.

Lead image: ESA/Hubble & NASA, C. Murray, J. Maíz Apellániz

Help us improve.