Dark energy is the term for the unknown cause of the accelerating expansion of the universe. Observations of Type Ia supernovae (1998) and detailed CMB measurements show the universe is expanding faster over time and that ordinary plus dark matter account for only about a third of the critical density. Proposed explanations include the cosmological constant (vacuum energy) and dynamic quantum fields; each faces major theoretical challenges, including a large mismatch between quantum predictions and observations. Ongoing astronomical surveys and particle-physics experiments aim to narrow the possibilities.

What Is Dark Energy — And Why It Matters

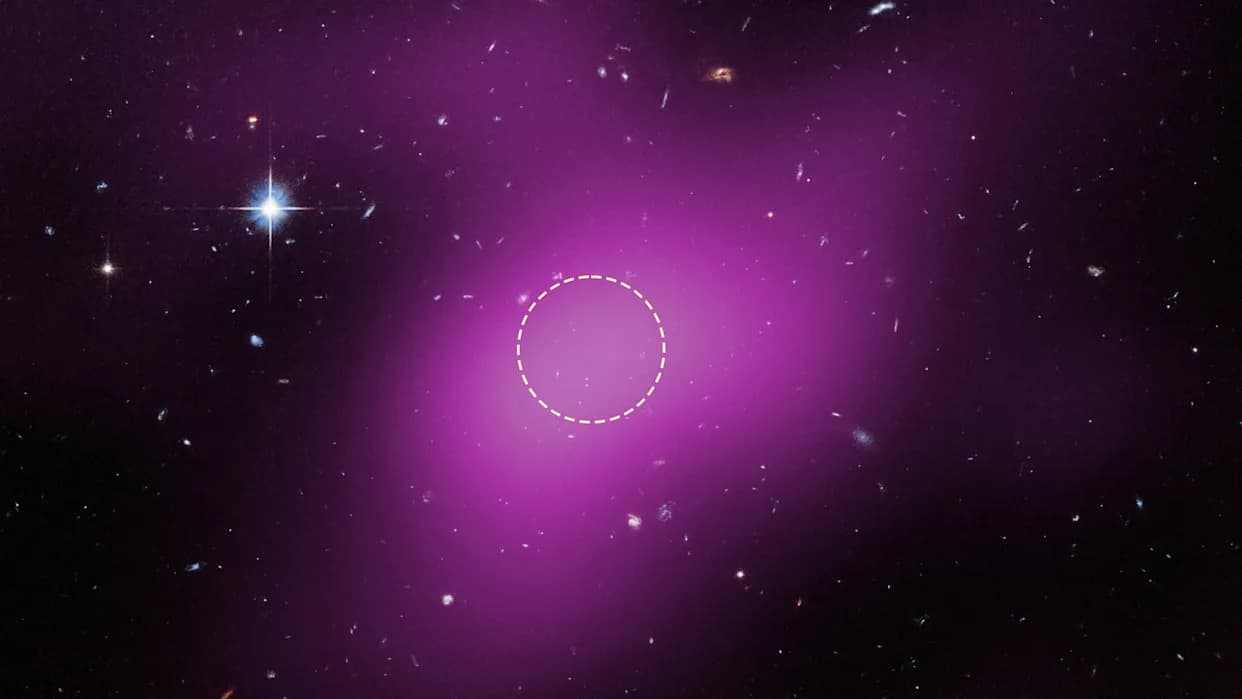

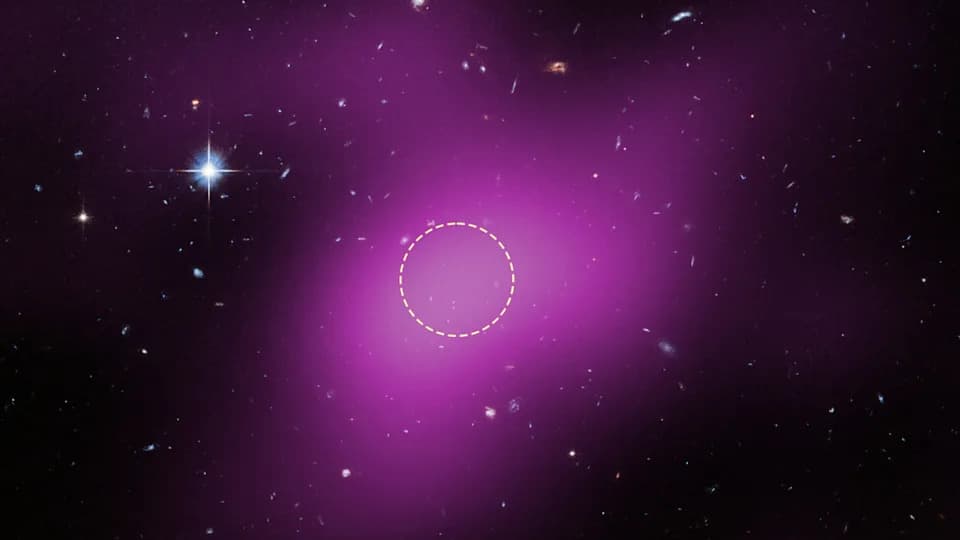

Dark energy is one of the most puzzling concepts in modern physics. It is the name scientists give to whatever is driving the observed acceleration of the universe’s expansion. Unlike dark matter, which can be mapped through its gravitational effects, dark energy is not well understood and is mainly defined by the role it must play to make cosmological observations consistent.

Observational Evidence

In 1998, two teams studying Type Ia supernovae—used as reliable “standard candles” for measuring cosmic distances—found that distant supernovae were dimmer than expected. That dimness implied the universe’s expansion is speeding up rather than slowing down. Subsequent measurements, including detailed maps of the Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB), baryon acoustic oscillations, and large-scale structure surveys, have confirmed that finding.

CMB data allow cosmologists to compute a critical density for the universe. The combined contributions from ordinary matter and dark matter add up to significantly less than that critical density—only roughly one third—leaving most of the universe’s energy budget unexplained unless another component, which we call dark energy, fills the gap.

Theoretical Explanations and Problems

One simple explanation is the cosmological constant, a uniform energy density inherent to space itself (sometimes described as the energy of the vacuum). If this vacuum energy has a constant density per unit volume, then as space expands the total amount of vacuum energy increases in proportion to new volume, producing a persistent repulsive effect that accelerates expansion.

However, quantum-field theory estimates for vacuum energy exceed the observed value by many orders of magnitude—a severe theoretical mismatch known as the cosmological constant problem. Alternative ideas model dark energy as a dynamic quantum field (sometimes called quintessence) that evolves over time. Such fields can, in principle, produce cosmic acceleration but must be carefully tuned so they do not produce detectable effects at planetary or solar-system scales.

To reconcile the absence of local effects, theorists have proposed mechanisms such as a "chameleon" field, which becomes screened in the presence of dense matter and therefore has negligible influence inside galaxies or solar systems while still driving cosmic acceleration on large scales.

Why This Matters

Although some details remain speculative, independent lines of cosmological evidence strongly indicate the existence of a dark-energy–like component. When combined, observations currently favor a model with dark energy at high statistical confidence (commonly reported in the literature as a very strong detection).

Understanding dark energy is crucial because it affects the ultimate fate of the universe, informs fundamental physics (including gravity and quantum field theory), and may point to new particles or interactions. Current and upcoming projects—such as the Dark Energy Survey, the Euclid mission, the Vera C. Rubin Observatory’s Legacy Survey of Space and Time (LSST), and precision experiments at particle colliders—aim to narrow the possible explanations and reveal the physics behind cosmic acceleration.

Conclusion: Dark energy remains one of the biggest open questions in cosmology. Ongoing astronomical surveys and laboratory experiments may soon tighten constraints or uncover new evidence that points to a deeper theoretical understanding.

Help us improve.