Although the universe is expanding, that expansion is most important on very large scales. Space itself stretches so more distant galaxies recede faster (roughly ~70 km/s per megaparsec), but local gravitational attraction can dominate over expansion. As a result, nearby galaxies such as Andromeda are moving toward the Milky Way and may merge in about 4–5 billion years. The discovery of accelerating expansion (dark energy) complicates the distant future but does not prevent local collisions on humanly meaningful timescales.

If Space Is Expanding, How Do Galaxies Still Collide?

Many readers ask a deceptively simple question: if the universe is expanding, why do galaxies sometimes smash into one another instead of only flying apart? The short answer is that cosmic expansion matters most on the very largest scales, while gravity can dominate locally.

Space Is Stretching, Not Throwing Things Like Shrapnel. The modern cosmological picture is not an explosion that flings galaxies through preexisting space. Instead, space itself is expanding. That stretching makes more distant galaxies appear to recede faster from us — a relationship quantified by Hubble's law.

A helpful analogy is a very stretchy ruler with marks drawn on it: when you stretch the ruler, widely separated marks move apart faster than marks that are close together. In the universe, the recession speed grows with distance: roughly speaking, space expands by about 70 kilometers per second for every megaparsec (one megaparsec ≈ 3.26 million light-years), though precise measurements of the Hubble constant vary slightly depending on the method.

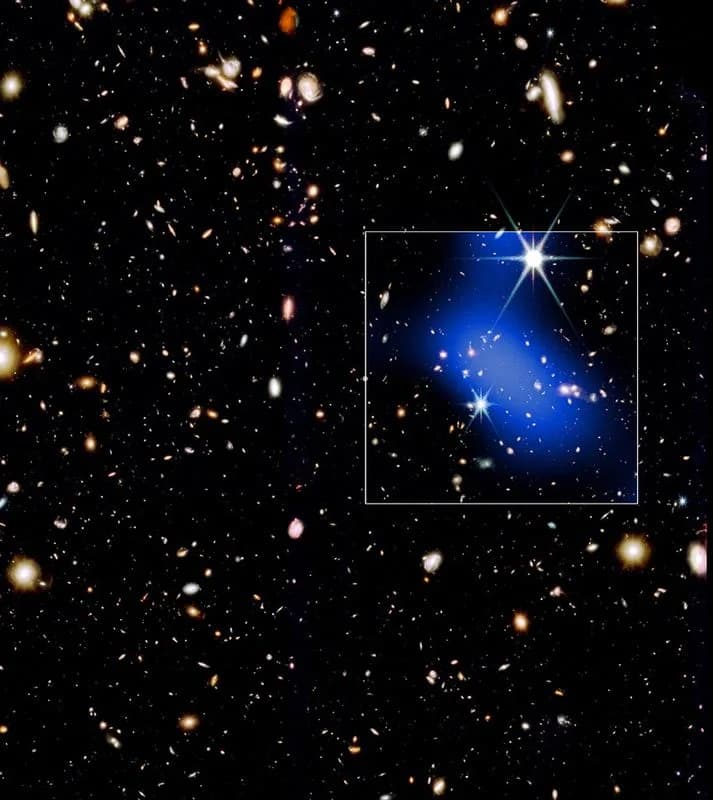

Local Motion Can Outrun Expansion. Recession due to expansion is not the whole story. Galaxies also have motions through space driven by gravity. If that motion is large enough, it can overcome the relatively small expansion at short distances. The Andromeda galaxy is a clear example: at about 2.5 million light-years away, it should be receding slowly from us due to expansion, but instead it is moving toward the Milky Way at roughly 110 km/s. That mutual gravitational attraction means the two galaxies are on a collision course and may merge in roughly 4–5 billion years.

Gravity Creates Bound Systems That Don’t Expand. Einstein’s general relativity describes gravity as curvature of spacetime. When objects are gravitationally bound — like planets around a star, or galaxies within a group — the expansion of the universe does not stretch the space inside those bound systems. The cosmic expansion stretches the space around the bound region, but the binding forces hold the system together, allowing objects inside it to orbit, approach one another, or eventually collide.

Dark Energy and the Long-Term Outlook. In 1998 astronomers discovered that the universe’s expansion is accelerating, driven by a still-mysterious component called dark energy. Depending on the properties of dark energy, the long-term fate of bound structures could change. In many plausible scenarios, gravity will keep galaxy groups and clusters intact indefinitely. In more exotic hypotheticals — for example, certain forms of dark energy that grow stronger over time — even bound structures could eventually be pulled apart in a so-called "big rip." That outcome is speculative and depends on the poorly understood physics of dark energy.

Bottom Line: There is no contradiction between cosmic expansion and galaxy collisions. Expansion dominates at intergalactic distances, but gravity wins locally. Collisions like the future Milky Way–Andromeda merger occur because local gravitational attraction overcomes the gentle stretching of space at those scales. And whatever the universe’s ultimate fate, these processes unfold over billions to trillions of years, far beyond our daily experience.

Want to learn more? For deeper explanations and visualizations, look for readable articles by science writers such as Ethan Siegel and resources on Hubble’s law, the Local Group, and dark energy.

Help us improve.