Solarion ariena is a newly described single‑celled protist with a sun‑like body and radiating stalks tipped by kinetocysts that capture bacteria. Discovered by Matthew Brown in an anaerobic marine culture, it defines a new phylum (Caelestes) within the proposed supergroup Disparia. The organism retains rare mitochondrial genes and a mitochondrial SecA pathway without the typical SecYEG translocon, suggesting repurposed or ancestral protein‑transport mechanisms. Its atypical life cycle and cellular features provide fresh clues about the origin of mitochondria and early eukaryotic evolution.

A Living Sun: Scientists Discover Solarion ariena, a Sun‑Like Microbe That Preserves Mitochondrial Relics

Researchers have identified a previously unknown single‑celled organism, Solarion ariena, whose striking sun‑like shape and unusual molecular features offer new clues about the earliest stages of eukaryotic evolution.

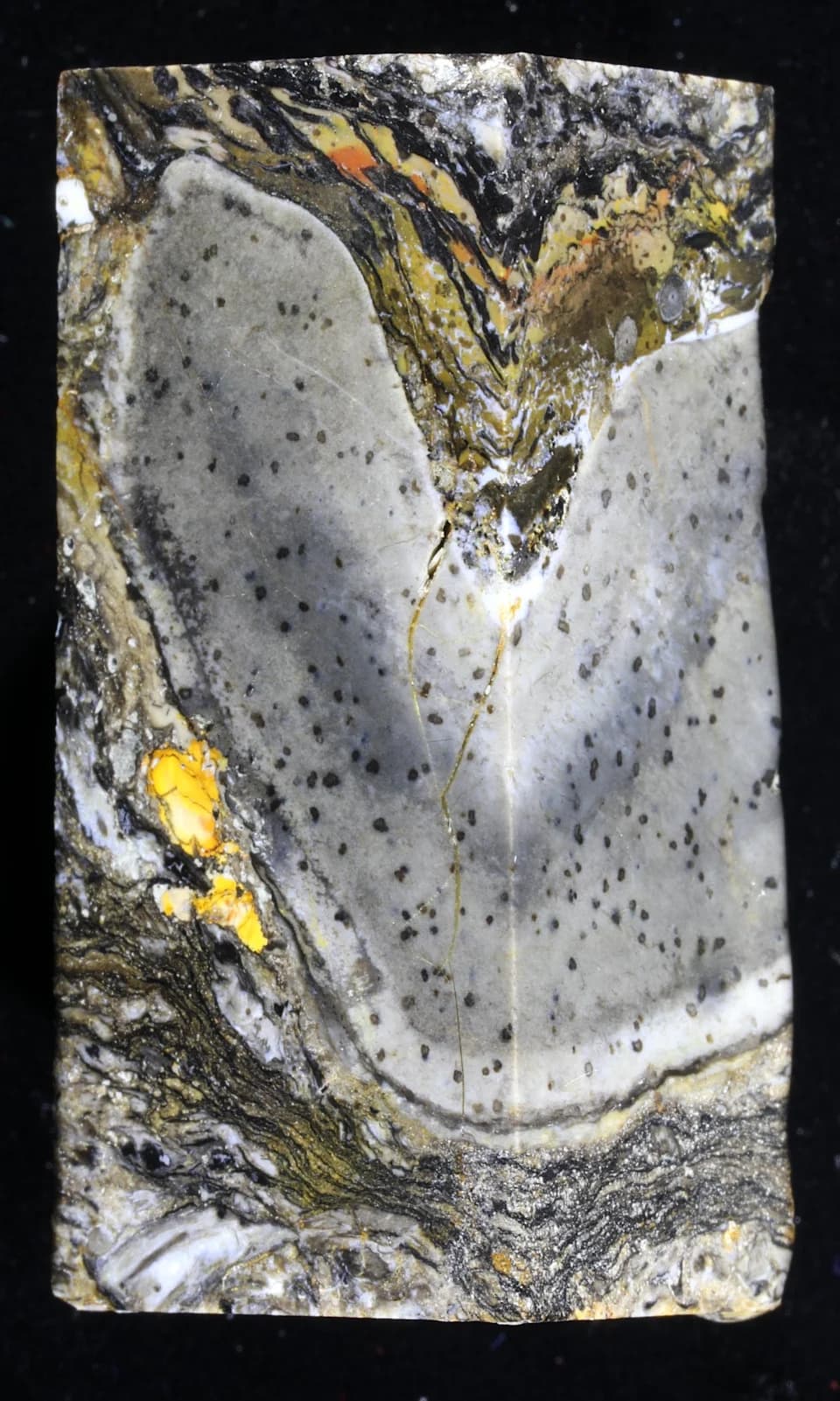

Morphology and discovery. Solarion ariena has a spherical cell body with radiating stalks, each tipped by a small hollow orb called a kinetocyst. Those kinetocysts enclose filaments that capture and pierce bacterial prey, giving the organism a cartoonish “sun” appearance. Biologist Matthew Brown of Mississippi State University discovered the species unexpectedly in a laboratory culture of anaerobic marine protozoans; it proved culturable and genetically related to the protist Meteora sporadica.

Life cycle and cellular oddities. The species displays at least two distinct phases: a common sun‑like phase that bears extrusomes for feeding, and an alternate flagellated phase that is oblong and mobile. Some flagellates revert to the sun form. Structurally, Solarion typically carries a single centriole — unusual because most eukaryotic cells have two — and its stalk‑orb arrangement differs from Meteora (which bears multiple orbs per stalk). Based on these traits, Solarion and Meteora have been grouped into a newly proposed phylum, Caelestes, within the suggested supergroup Disparia.

Remnants of ancient mitochondria. What excites evolutionary biologists is that Solarion retains rare mitochondrial genes and unexpected molecular machinery. The team found proteins encoded inside its mitochondria that, in most eukaryotes, are nucleus‑encoded. They also detected a SecA pathway localized to the mitochondria, but could not find the usual SecYEG translocon that typically pairs with SecA to move proteins across membranes. That unusual configuration suggests the pathway may be a relic repurposed from an ancestral prokaryotic partner or an alternative transport mechanism preserved from deep evolutionary history.

Why this matters. Mitochondria are central to eukaryotic metabolism and played a key role in enabling multicellular life. Finding vestigial mitochondrial genes and an atypical SecA pathway in Solarion gives researchers a rare window into intermediate states between free‑living bacteria and fully integrated organelles, helping to reconstruct steps in how early eukaryotes acquired and integrated bacterial partners.

“The discovery of S. ariena broadens our understanding of early eukaryotic evolution and facilitates the study of proto‑mitochondrial metabolic remnants, shedding light on the complexity of ancient eukaryotic life,” Matthew Brown and colleagues write in their study published in Nature.

Open questions and next steps. The exact position of Disparia within the eukaryotic tree remains unresolved. Brown’s team suggests that Solarion may have been missed in environmental surveys because it occupies narrowly specific or cryptic habitats, or is genuinely rare. Broader environmental sampling and refined phylogenetic methods will be needed to place Disparia precisely and to determine whether additional related species exist.

Conclusion. By preserving both unusual anatomy and molecular remnants of ancient mitochondrial systems, Solarion ariena and its relatives in Caelestes provide valuable evidence about how primitive eukaryotic cells may have evolved from prokaryotic ancestors. Continued study of these protists could illuminate the cellular and metabolic steps that ultimately made complex life possible.

Help us improve.