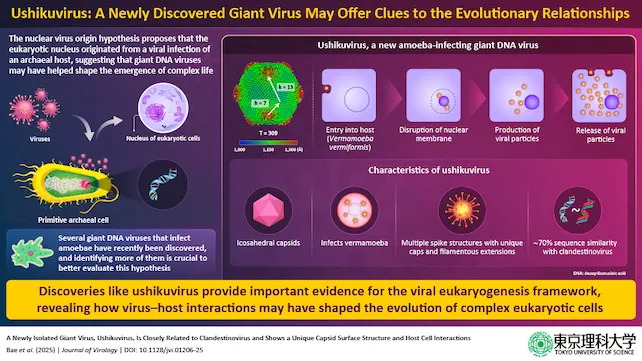

The newly discovered giant virus ushikuvirus, isolated from an amoeba in Ushiku-numa pond near Tokyo, forces host cells to enlarge, builds a membrane-bound viral factory, and destroys the host nuclear membrane during replication. Its distinctive capsid features and replication strategy add important comparative data to the study of giant viruses. The find bolsters discussion of the viral eukaryogenesis hypothesis — which proposes viruses contributed to the origin of the eukaryotic nucleus — and underscores how viruses have shaped evolutionary history.

New Giant Virus 'Ushikuvirus' From Japanese Pond Offers Clues to the Origin of Eukaryotic Cells

Researchers in Japan have isolated a previously unknown giant virus from an amoeba in Ushiku-numa, a freshwater pond in Ibaraki Prefecture. Named ushikuvirus, the discovery expands the known diversity of giant viruses and provides fresh evidence relevant to theories about how complex eukaryotic cells evolved.

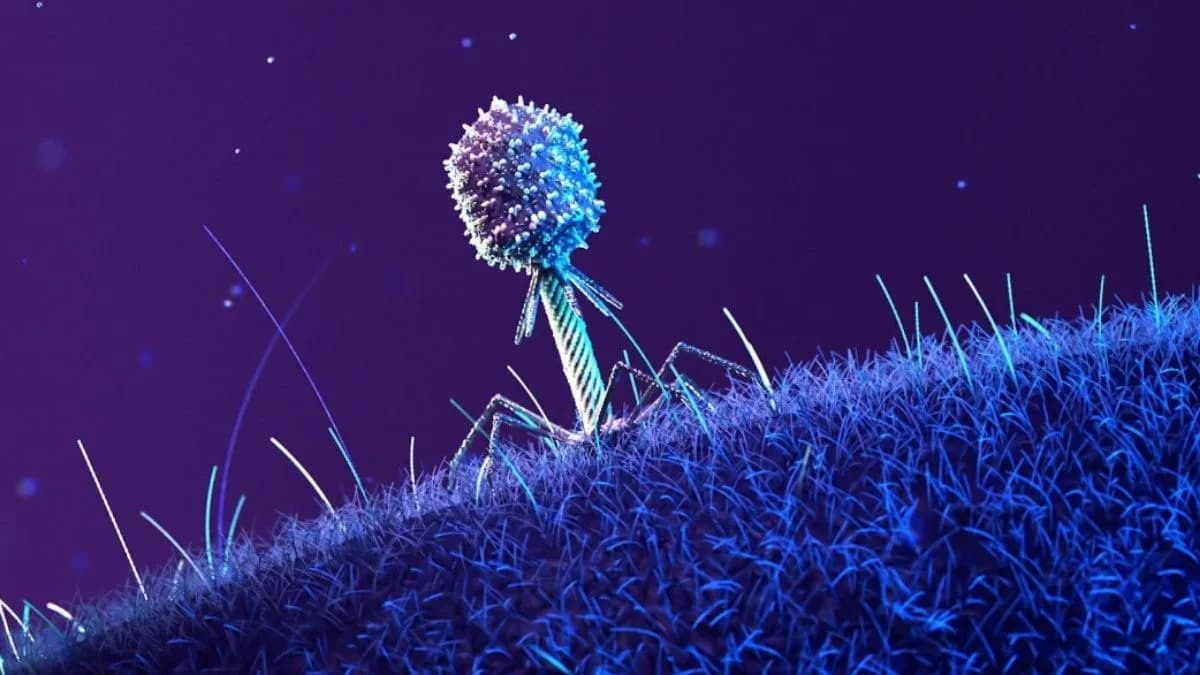

Giant viruses were overlooked for much of the history of virology because their large size led early scientists to mistake them for bacteria. Only in recent decades have researchers begun to appreciate how widespread and diverse these enormous DNA viruses are.

What Makes Ushikuvirus Special?

Ushikuvirus infects the amoeba Vermamoeba vermiformis. It forces infected host cells to grow to abnormally large sizes, assembles a prominent membrane-bound "viral factory" for replication, and destroys the host's nuclear membrane rather than preserving the nucleus during replication. Its capsid is spiky, with distinctive caps and fibrous appendages that set it apart from related giant viruses such as medusaviruses and clandestinovirus.

Why This Matters

Giant viruses are important not only because of their size, but because they blur traditional boundaries between viruses and cellular life. Some researchers propose that giant DNA viruses may have played a role in the origin of the eukaryotic nucleus — a hypothesis called viral eukaryogenesis. First proposed in 2001 by Masaharu Takemura, this idea suggests a large DNA virus could have become integrated into an ancestral prokaryote and evolved into a membrane-bound nucleus.

The discovery of ushikuvirus contributes new comparative data: its combination of virus-factory formation and host-nuclear disruption contrasts with other giant viruses that preserve and replicate within host nuclei. These similarities and differences help scientists reconstruct viral evolution and assess the plausibility of virus-driven steps toward cellular complexity.

"Giant viruses can be said to be a treasure trove whose world has yet to be fully understood," says Masaharu Takemura, a coauthor on the study. "One future possibility of this research is to offer humanity a new perspective that connects the world of living organisms with the world of viruses."

Broader Evolutionary Impacts

Viruses influence evolution in multiple ways. They are major agents of horizontal gene transfer and, in the case of retroviruses, can integrate into host genomes. Ancient retroviral sequences now account for as much as roughly 8% of the human genome, and such viral contributions have been linked to important innovations like placenta development and potentially myelin formation in early vertebrates.

Ushikuvirus was described by researchers led by Takemura and colleagues and the study was published in the Journal of Virology. The authors say the new isolate will stimulate discussion about the phylogeny of Mamonoviridae-related viruses and help clarify how giant viruses diversified and what role they may have played in the origin of eukaryotes.

Reference: Study published in the Journal of Virology.

Help us improve.