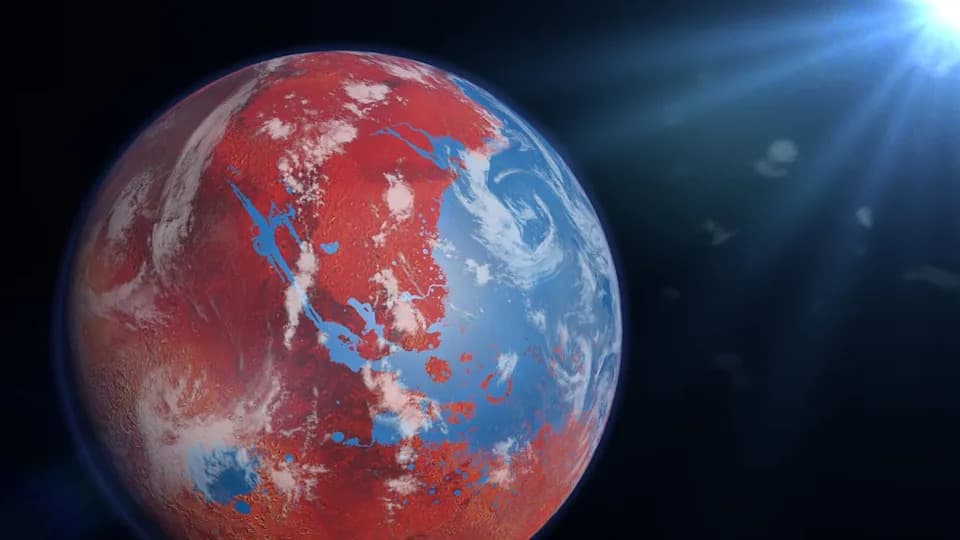

Researchers report the identification of at least eight skylights in Hebrus Valles that likely mark karstic caves formed when acidic water dissolved carbonate and sulfate rocks more than 3.5 billion years ago. Data from Mars Global Surveyor, Mars Odyssey and the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter support the presence of carbonate and sulfate deposits and possible subsurface ice. These caves could preserve ancient microbial biosignatures and offer natural shielding for future human outposts, but accessing them poses significant engineering challenges.

Colossal Water‑Carved Caves in Hebrus Valles May Hide Traces of Ancient Martian Life

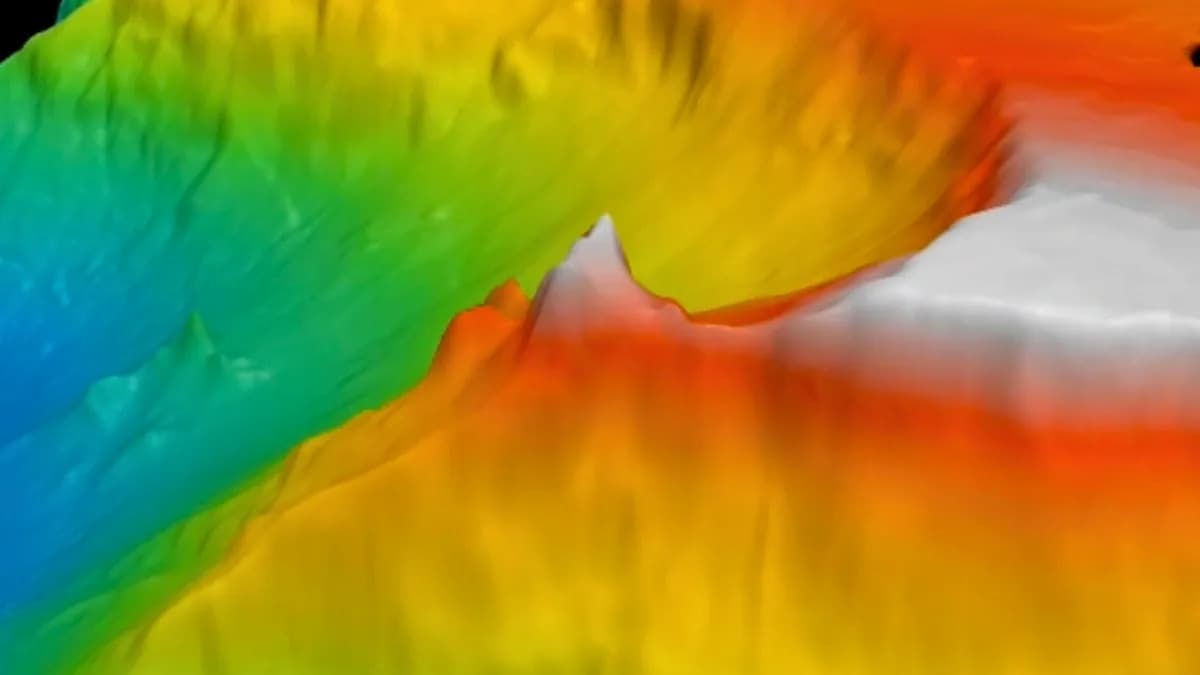

Scientists have identified what appear to be large karstic caves in Hebrus Valles on Mars — voids likely formed when slightly acidic water dissolved carbonate and sulfate bedrock more than 3.5 billion years ago. These underground caverns are marked at the surface by at least eight skylights, pits tens to over 100 meters across that likely formed when ceilings collapsed into empty spaces below.

What the team found

The Hebrus Valles region, located between the extinct volcano Elysium Mons and the low plain of Utopia Planitia in Mars' northern midlatitudes, shows abundant signs of past surface water and hydrated minerals. Mineral maps and hydrogen detections indicate substantial carbonate rocks such as limestone and sulfate minerals like gypsum. Together, these observations support the interpretation that water once deposited sediments here and later dissolved them to form karstic cave systems.

How the caves were identified

The discovery is based on analysis of archived data from multiple missions. The researchers used mineralogical maps from the Thermal Emission Spectrometer on Mars Global Surveyor, hydrogen measurements from the Gamma‑Ray Spectrometer on Mars Odyssey, and high‑resolution terrain models and imagery from HiRISE on the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter. These datasets were combined to show a consistent picture: rocks that can dissolve in water, evidence for past and possibly present subsurface water or ice, and surface skylights without crater ejecta or raised rims.

Why these caves matter

Karstic caves are among the most promising places to search for preserved biosignatures. When they formed, these caves would have offered stable, water-rich microenvironments that could have supported microbial life. Today the cave interiors would be shielded from Mars' harsh surface conditions — extreme temperature swings, frequent dust storms, and damaging ultraviolet and cosmic radiation — improving the chances that any ancient biological traces remain intact.

"With expected technological advances in the coming decades, if missions are specifically designed for these targets, we believe that in situ exploration of Martian karstic caves is an achievable goal," said Chunyu Ding of the Institute for Advanced Study at Shenzhen University.

Challenges and exploration concepts

Accessing these caves will be technically demanding. Radio signals will be attenuated by surrounding rock, complicating communications with orbiters. Not all skylights are sheer vertical shafts; several show stepped piles of rock that might allow staged descent. Proposed exploration concepts include coordinated robotic chains: wheeled rovers or climbers that descend in stages while acting as relays, winch‑deployed climbers, and small aerial rotorcraft that can fly through skylights to ferry data and payloads.

Potential benefits for future human missions

Beyond scientific value, subterranean cavities could provide natural shielding for future human habitats, protecting astronauts and equipment from radiation and surface weather. If sufficiently accessible and stable, such caves could become high‑value sites for both life detection and long‑duration human operations.

The results from the team led by Chunyu Ding and Ravi Sharma were published Oct. 30 in The Astrophysical Journal Letters. While Hebrus Valles may not be unique, the authors note that karstic caves will be geographically restricted to regions with the right rock types, preserved subsurface volatiles, and long periods of geologic stability.

Help us improve.