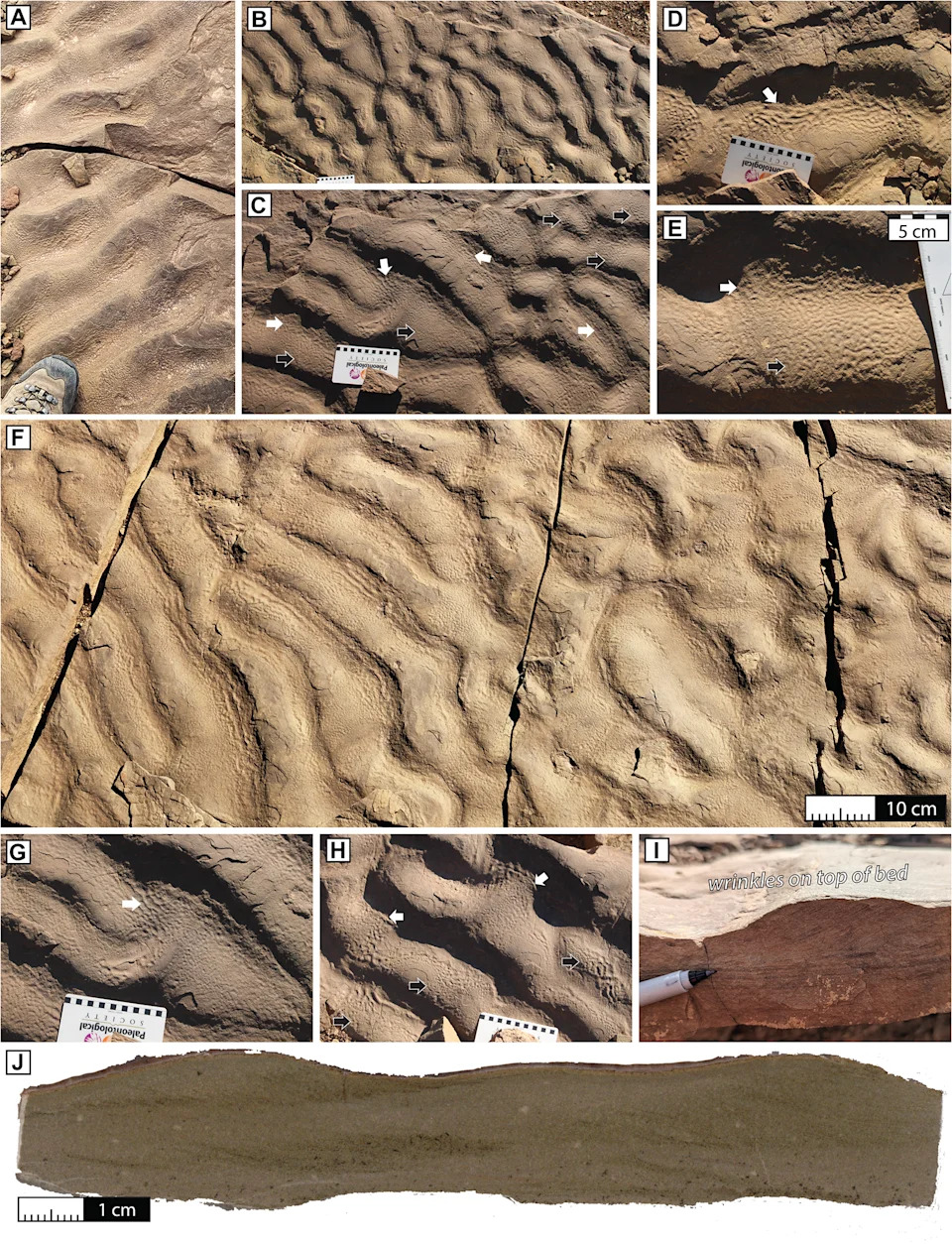

Researchers led by Rowan Martindale identified wrinkle-like fossil impressions on deep-water turbidites in Morocco’s Central High Atlas Mountains. The deposits formed about 180 million years ago at ~180 meters depth, too deep for photosynthesis. Chemical analyses indicate a biological origin, and the team argues the textures record chemosynthetic microbial mats that fed on compounds produced when underwater landslides buried organic material. The discovery suggests scientists should look for such fossils in deeper, unstable marine deposits as well as shallow settings.

Scientists Find Unexpected 'Wrinkle' Fossils on Deep Moroccan Seafloor — A Clue to Ancient Chemosynthetic Life

Researchers discovered surprising wrinkle-like fossil impressions preserved on deep-water turbidites in Morocco’s Central High Atlas Mountains, a find that broadens where scientists should look for ancient life.

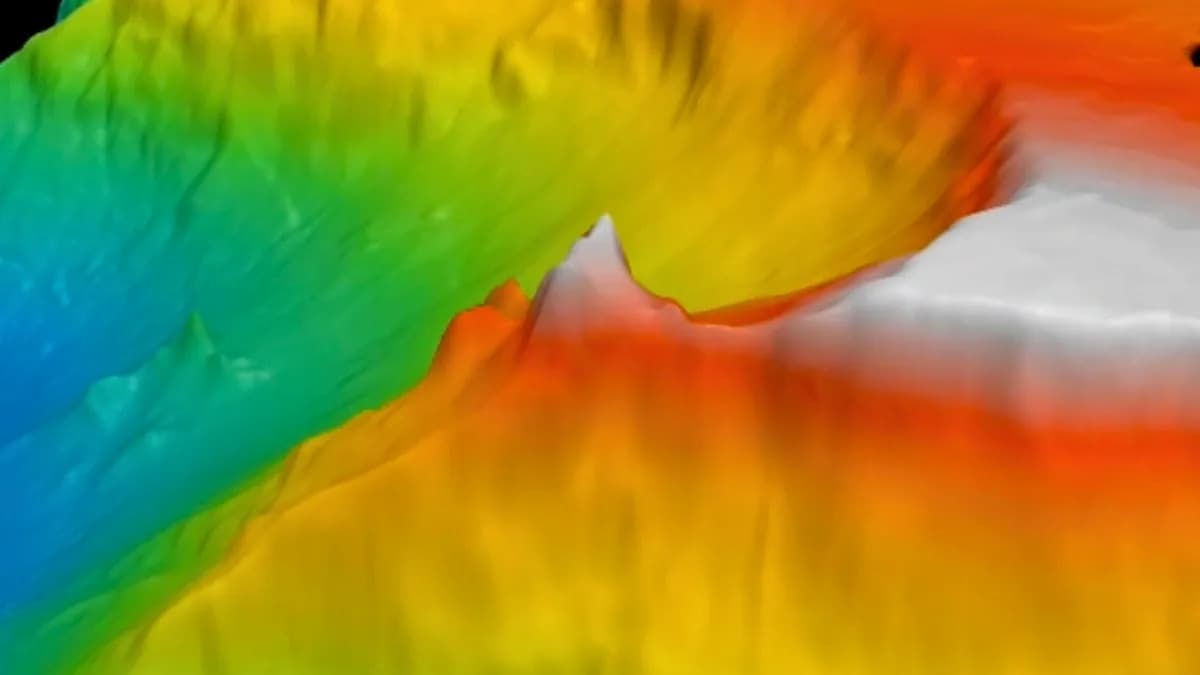

The imprints were found in the Dadès Valley on fine sandstone and siltstone that were deposited as turbidites — layers laid down by underwater landslides — roughly 180 million years ago during the Jurassic. Sedimentology indicates those deposits formed at depths of about 590 feet (180 meters), far below the sunlit zone where photosynthetic microbial mats normally form.

Why These Wrinkles Matter

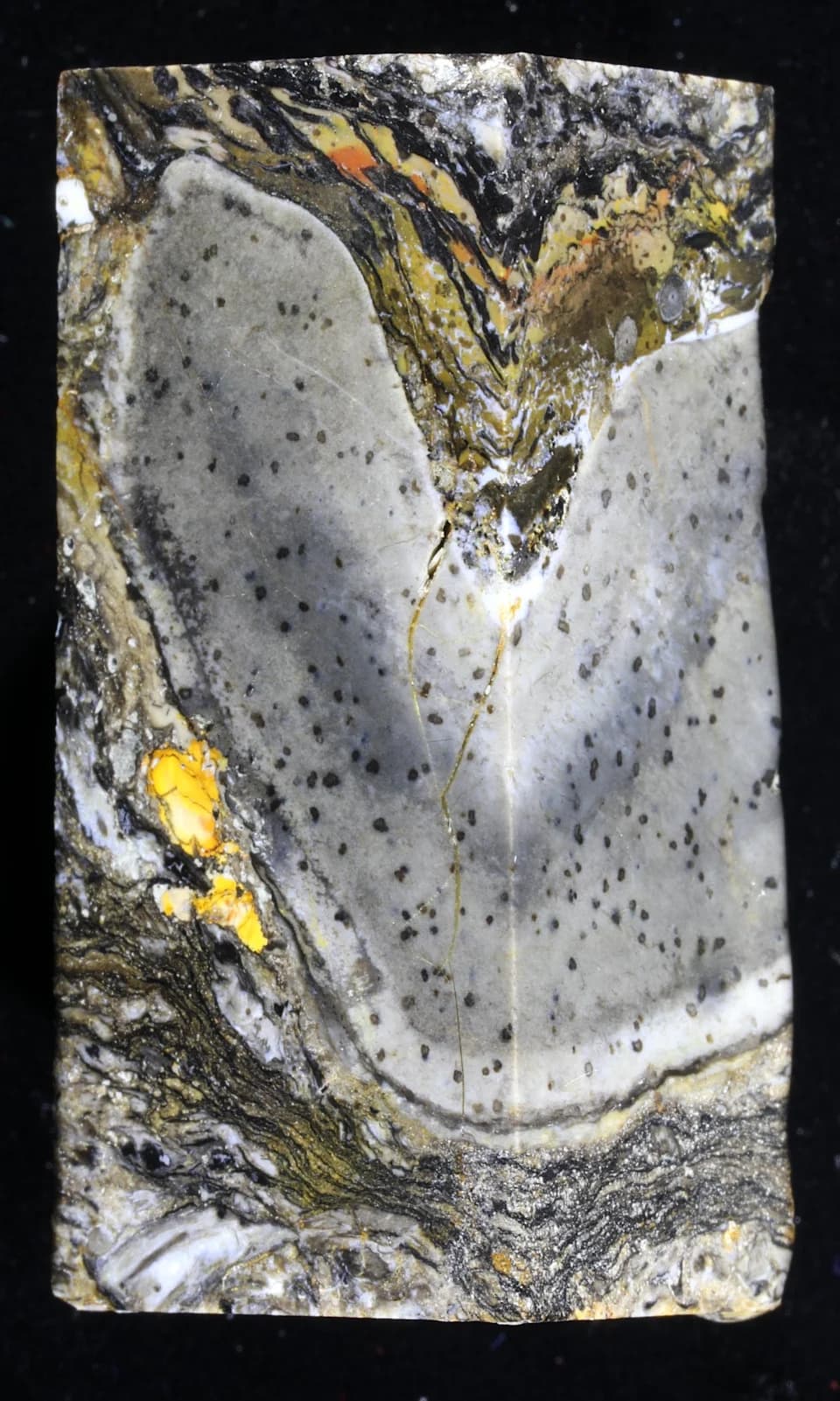

At first glance the ripple-like textures resemble the delicate surface patterns left by photosynthetic microbial mats. But the depth of deposition makes a photosynthetic origin unlikely; so little light would have reached 180 meters that photosynthesis could not have sustained a mat community there. Chemical analyses of the host layers, however, revealed elevated carbon concentrations consistent with a biological source.

Lead author Rowan Martindale, a geobiologist at the University of Texas at Austin, and colleagues suggest these structures record chemosynthetic microbial communities — microbes that obtain energy from chemical reactions (for example from hydrogen sulfide or methane) rather than sunlight. Modern chemosynthetic mats thrive where chemical energy is available, such as on continental shelves and in environments influenced by organic-rich debris flows.

Role Of Underwater Landslides

The team proposes that repeated underwater landslides (debris flows) delivered organic-rich material from the continent into deeper water. As that organic matter decomposed on the seafloor it would have generated reduced compounds (e.g., methane, hydrogen sulfide) that could fuel chemosynthetic microbes. Between debris-flow events mats could colonize the seafloor, and in some cases their surface textures were preserved when subsequent flows buried them.

“Wrinkle structures shouldn’t be in this deep-water setting,” Martindale said. “Wrinkle structures are really important pieces of evidence in the early evolution of life.”

The research, published Dec. 3 in the journal Geology, shows these wrinkle structures can be preserved in deeper, more dynamic marine settings than often assumed. That expands the search space for paleobiologists seeking evidence of ancient microbial ecosystems — including those fueled by chemical energy rather than sunlight — and may illuminate environments important for early life on Earth.

Implications: The find encourages geologists and paleobiologists to examine rocks that were originally deposited in deeper-water turbidite systems when searching for fossil microbial textures, not just shallow-water strata.

Help us improve.