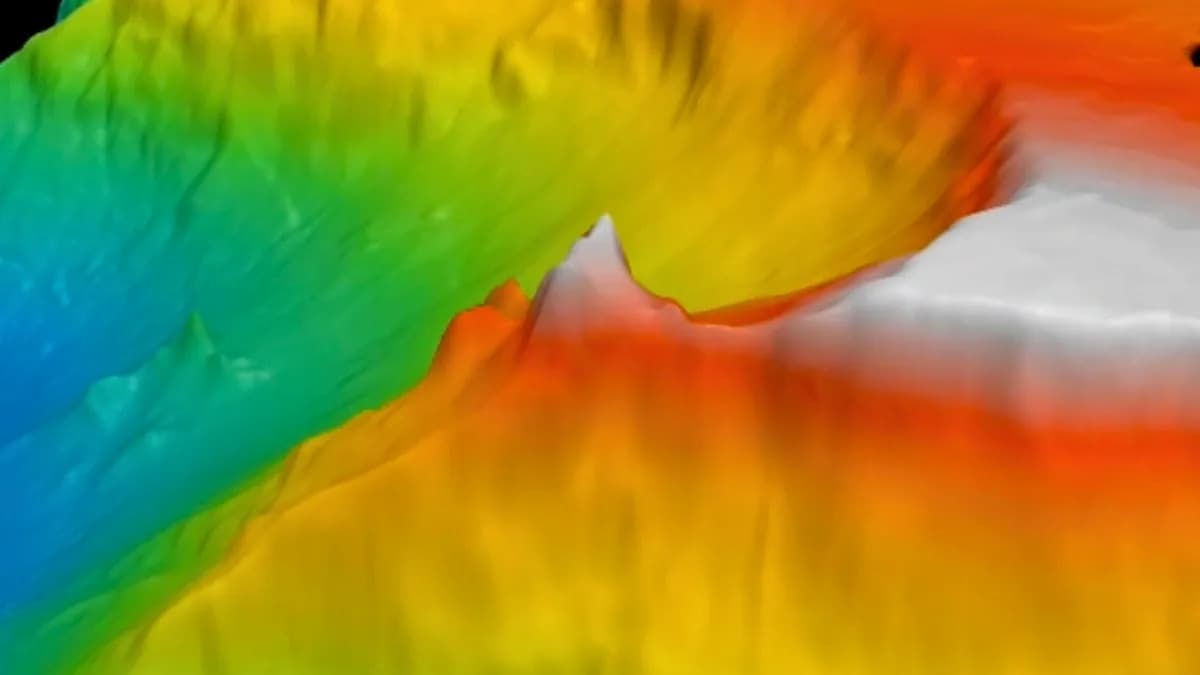

The Lost City Hydrothermal Field, discovered in 2000 more than 700 metres below the Mid‑Atlantic Ridge, features towering carbonate chimneys — including a 60‑metre monolith named Poseidon — and is the longest‑lived vent system known. Abiotic reactions between upwelling mantle and seawater produce hydrogen and methane that sustain oxygen‑free microbial ecosystems and a variety of invertebrates. A record 1,268‑metre mantle core recovered in 2024 may shed light on how life emerged on Earth and informs astrobiology research. Scientists warn that nearby deep‑sea mining rights granted in 2018 could create plumes that threaten the site, prompting calls for World Heritage protection.

The Lost City: A Hydrogen-Rich Underwater Realm Unlike Any Other on Earth

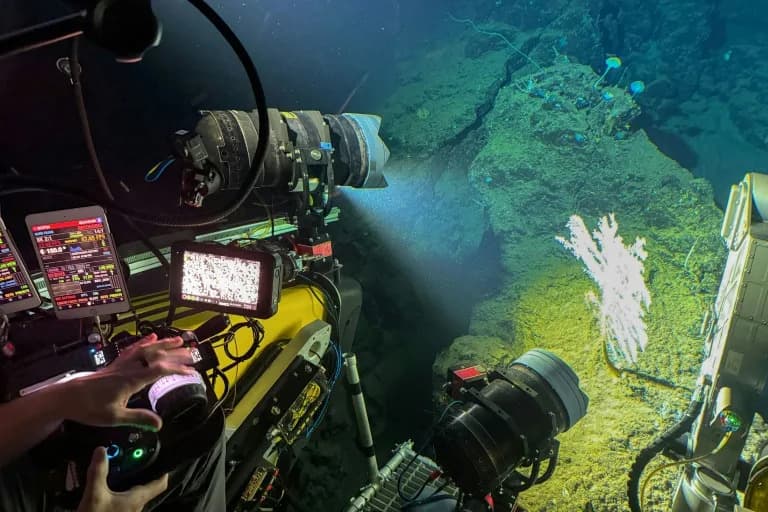

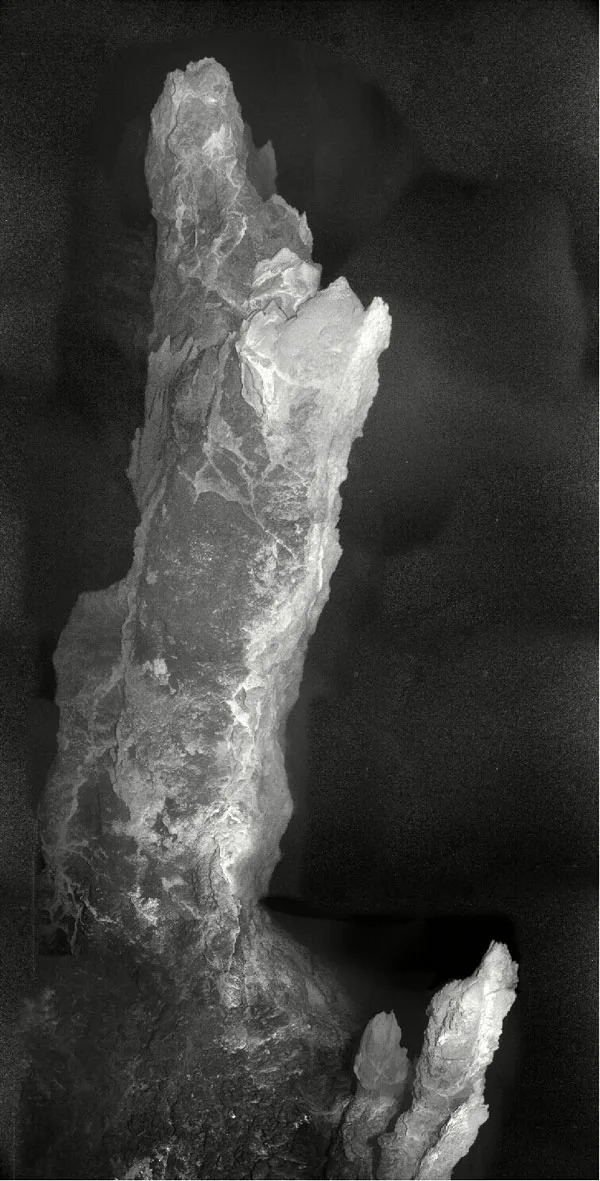

Near the summit of an underwater mountain west of the Mid‑Atlantic Ridge, a serrated forest of towering carbonate chimneys rises from the deep. Bathed in the eerie blue glow of remotely operated vehicles, these formations — from toadstool-sized stacks to a monolith named Poseidon more than 60 metres high — make up the Lost City Hydrothermal Field.

What Is the Lost City?

Discovered in 2000 at depths of more than 700 metres (roughly 2,300 feet), the Lost City is the longest‑lived hydrothermal vent system documented on Earth. Its calcite chimneys are far larger and longer‑lived than typical volcanic “black smoker” vents, and the field’s unique mineralogy and chemistry create an environment found nowhere else.

An Ancient, Hydrogen‑Rich Ecosystem

For at least 120,000 years — and possibly much longer — upwelling mantle material in this region has reacted with seawater to generate abundant hydrogen, methane and other reduced gases. These hydrocarbons form through abiotic chemical reactions on the seafloor rather than from atmospheric CO2 or sunlight, and they feed unusual microbial communities that do not rely on oxygen.

Chimneys that emit fluids as warm as ~40 °C (104 °F) host abundant snails and crustaceans; larger animals such as crabs, shrimp, sea urchins and eels occur but are relatively rare. Despite the extreme conditions, the site supports a rich and distinctive ecosystem that has persisted for millennia.

Significance for Origins of Life and Astrobiology

In 2024 researchers recovered a record 1,268‑metre mantle core from the Lost City area. Scientists hope the core will preserve mineral and chemical signatures that help explain how life could have arisen on early Earth under conditions like those in this field.

"This is an example of a type of ecosystem that could be active on Enceladus or Europa right this second," microbiologist William Brazelton told The Smithsonian in 2018. "And maybe Mars in the past."

How It Differs From Black Smokers

Unlike black smokers — which are driven by magmatic heat and emit iron‑ and sulfur‑rich minerals — the Lost City does not depend on magma. Its carbonate chimneys produce far more hydrogen and methane (up to ~100 times more, by some measurements), and their large size implies much longer lifespans than typical volcanic vents.

Threats And Conservation

Although the hydrothermal field itself contains no high‑grade ore deposits, the surrounding deep seafloor has attracted mining interest. In 2018, Poland was granted rights to prospect parts of the seafloor near the Lost City. Scientists warn that mining‑generated plumes or discharges could spread across the habitat and cause irreversible damage.

Because of its scientific, ecological and astrobiological importance, some researchers are urging that the Lost City be considered for UNESCO World Heritage protection to guard it from industrial disturbance.

For tens of thousands of years, the Lost City has stood as a testament to life's resilience in extreme environments. Protecting it now would preserve a unique natural laboratory for understanding Earth's deep biosphere and the possible habitats of life beyond our planet.

An earlier version of this article was published in August 2022.

Help us improve.