Scientists have uncovered a 307-million-year-old skull on Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia, belonging to Tyrannoroter heberti—one of the earliest-known plant-eating land vertebrates. The fossil, described in Nature Ecology & Evolution, sheds new light on when tetrapods (four-limbed vertebrates) first moved into herbivorous niches.

The skull is roughly 4 inches (10 cm) long. Although Tyrannoroter superficially resembled a small reptile, it belongs to a group called microsaurs. Based on comparisons with related species, researchers estimate the whole animal was about 12 inches (30.5 cm) long with a stocky, blue-tongued-skink–like build.

Anatomy and Herbivory

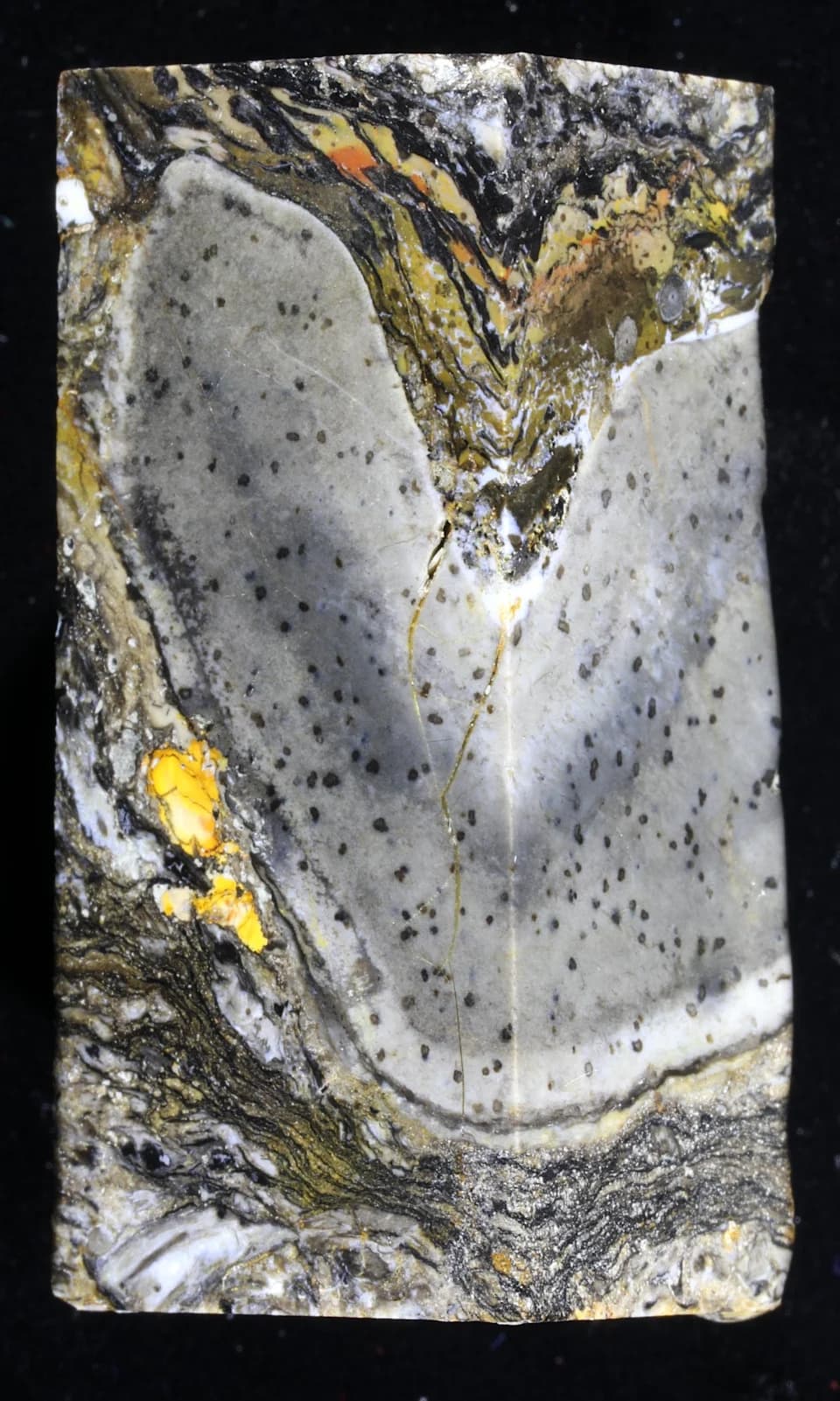

Tyrannoroter's somewhat triangular skull accommodated large cheek-muscle chambers and a set of specialized teeth adapted to crush, shred and grind plant material. CT scans revealed dozens of conical teeth on the roof of the mouth forming opposing dental fields—palatal teeth that occluded with teeth on the lower jaw—often described as a type of "dental battery" seen in herbivorous animals.

These features—downturned snout for cropping low vegetation, robust skull, large muscle chambers, and palatal dentition—support the interpretation that Tyrannoroter could process high-fiber plant material. The authors note it may also have eaten insects, but its skull appears better adapted for tougher vegetation than some contemporaries, such as Melanedaphodon from Ohio.

Researcher Arjan Mann holds a 3D-printed replica of the skull of Tyrannoroter heberti, a plant-eating creature that lived 315 million years ago during the Carboniferous Period in what is now the Canadian province of Nova Scotia, at the Field Museum in Chicago, in this handout image released on February 10, 2026. Picture taken with a mobile phone. Field Museum/Handout via REUTERS

Context and Significance

The specimen lived during the Carboniferous Period, an era of lush, coal-forming forests. The discovery shows that vertebrate herbivory and the ecological roles it supports existed much earlier than previously thought, indicating that terrestrial ecosystems resembling modern plant-dominated food webs were already taking shape some 307 million years ago.

"This discovery reveals vertebrate animals radiated into modern-like niches, including herbivory, much more quickly than we thought," said study senior author Hillary Maddin (Carleton University). Co-lead author Arjan Mann (Field Museum) added that insectivory may have been a key preadaptation that helped tetrapods acquire gut flora needed to digest plants.

Nomenclature and Discovery

The genus name Tyrannoroter means "tyrant digger," a nod to its relatively large size for the time and the interpretation that it was a burrower. The species name heberti honors Brian Hebert, who discovered the skull in a rocky cliff on Cape Breton Island.

Researchers used high-resolution CT scanning to study internal structures and dental arrangements without damaging the fossil. The find was reported by a team led by Maddin and Mann and published in Nature Ecology & Evolution.

Why it matters: The discovery pushes back the timeline for when tetrapods adopted herbivory and helps explain how early terrestrial ecosystems functioned—showing that adaptations for plant-eating evolved soon after vertebrates colonized land.