New magnetic fabric analyses of volcanic rocks from Colombia's Combia Volcanic Province (dated ~12–6 Ma) indicate that large-scale collision and crustal shortening between Central and South America had mostly wound down by about 10 million years ago. The study, led by Victor Piedrahita and J. Li, suggests the main collisional phase occurred earlier—during the Oligocene to middle Miocene—prompting a reassessment of northern Andes uplift timing. These findings affect models of landscape evolution, climate history, and seismic and volcanic hazard assessments.

New Study Pushes Major Central–South America Collision Back Before 10 Million Years Ago

The bedrock beneath northern South America records a much older chapter of Earth history: locked inside volcanic rocks are clues about when continents met, mountains rose, and the shape of the Americas changed. A new study argues that a major tectonic collision between Central and South America largely concluded earlier than many geologists have thought.

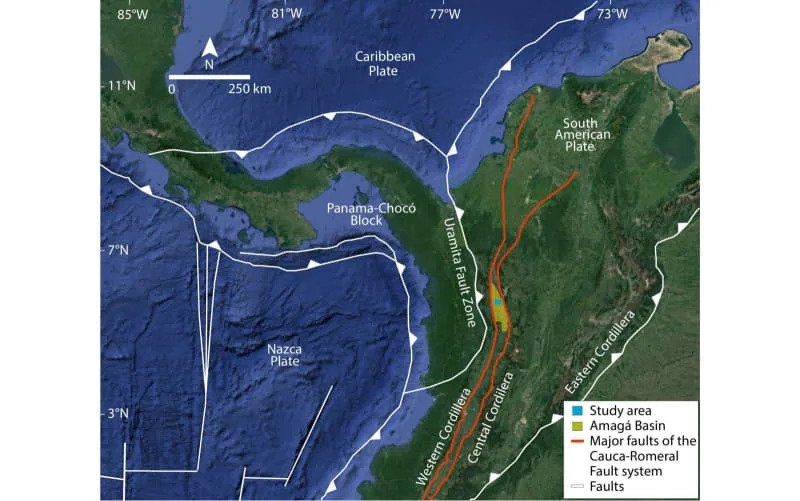

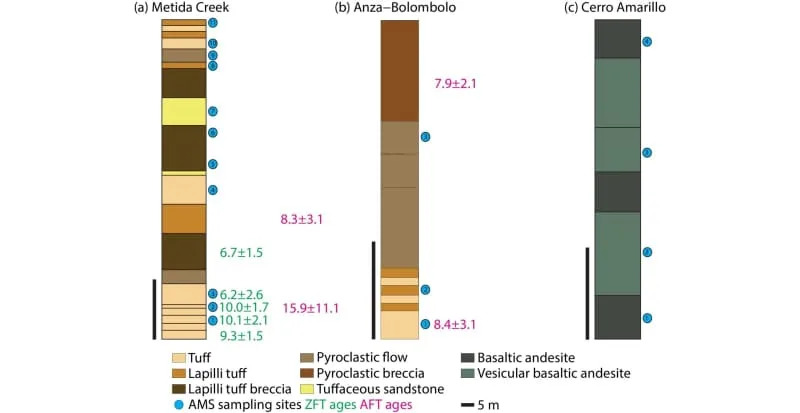

The international research team, led by Victor Piedrahita and J. Li, focused on Colombia's Northern Andes and in particular the Combia Volcanic Province. These volcanic deposits formed roughly between 12 and 6 million years ago, a period when the South American Plate interacted with the continental margin of Central America.

What the Rocks Reveal

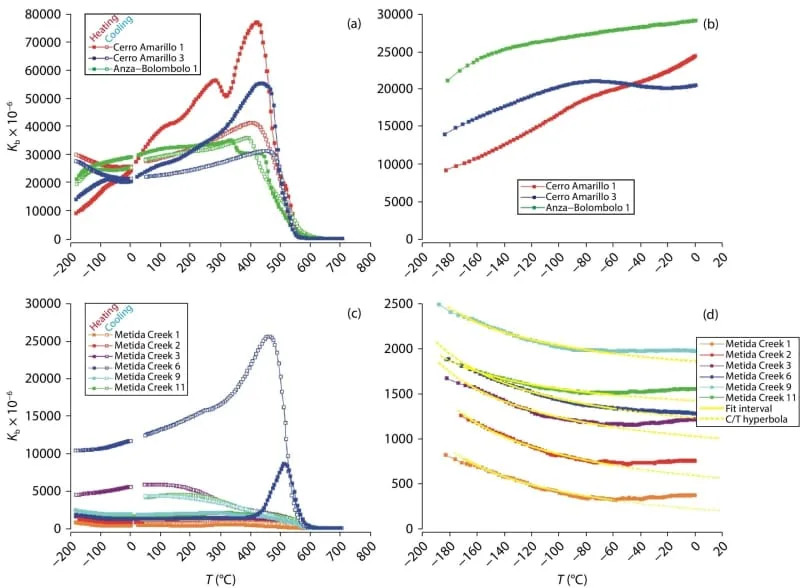

Volcanic rocks are valuable geological archives because they cool quickly and lock in the orientations of tiny magnetic minerals. Those minerals preserve a "magnetic fabric" that records whether the rock retains its original flow structure or has been later distorted by tectonic forces.

The research team applied magnetic fabric analysis to samples collected across multiple Combia sites. Many samples show magnetic patterns consistent with primary lava-flow and volcanic-debris emplacement, indicating little large-scale overprinting after formation. Some locations do show localized deformation, but these effects were limited and spatially inconsistent.

Key Finding

Taken together, the magnetic data indicate that large-scale crustal shortening in the northern Andes had largely tapered off by the time these volcanic rocks were deposited. In other words, the most significant collision-related deformation between Central and South America appears to have occurred earlier—mainly during the Oligocene to middle Miocene—so that by the late Miocene (around 10 million years ago) tectonic activity in this region was weaker and more localized.

Why This Matters

Refining the timing of continental collisions reshapes our understanding of Andes uplift and its downstream effects. The rise of the Andes influenced rainfall, river networks and ecosystems across South America and contributed to the evolution of the Amazon Basin and regional climate patterns. An earlier uplift timeline changes how researchers interpret past climate shifts, sedimentary records, and biogeographic history.

Accurate collision timing also improves plate-motion reconstructions and hazard models. Knowing when deformation intensified or waned helps geoscientists better assess seismic and volcanic risk, which can inform infrastructure planning in tectonically active regions.

Caveats and Next Steps

The authors emphasize that their conclusions are based on samples from a specific portion of the Northern Andes. Other sectors of the mountain belt could record different histories. Complementary evidence from sedimentary sequences, structural mapping, and fossil data will help test how broadly the earlier timing applies. Still, the magnetic fabric approach used here provides a strong, independent line of evidence that prompts re-evaluation of long-standing tectonic models.

The research was funded in part by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China to J. Li and Victor Piedrahita, and the results are published in the journal Earth and Planetary Physics.

Help us improve.