A new study in Nature Geoscience explains how small fragments of continental crust can end up stranded in the middle of oceans. High-resolution 3D models show that slow, oblique rifting and reactivated faults from past supercontinent collisions can isolate narrow continental ribbons and carry them onto young oceanic seafloor via transform faults. The process is gradual and can take up to about 30 million years, reconciling these odd crustal pieces with standard plate-tectonic theory.

Oceanic Orphans: How Supercontinent Breakups Stranded Pieces Of Continental Crust

Scattered around the globe—from the opening Red Sea to offset mid-ocean ridges in the Atlantic—scientists have identified more than a dozen small fragments of continental crust lodged well away from any continent. For decades these geological misfits puzzled researchers and were even once cited as evidence against plate tectonics, as João Duarte of the University of Lisbon has pointed out. A new study in Nature Geoscience provides a clear explanation: these continental castaways are a natural product of the chaotic first stages of supercontinent breakup.

How Continental Pieces End Up in the Ocean

When a continent rifts, it typically forms mid-ocean spreading centers—long linear zones where upwelling magma creates new basaltic oceanic crust and pushes plates apart. Oceanic crust is thin, dense and relatively young, while continental crust is thicker, more buoyant, often granitic, and can be billions of years old. Finding ancient continental slivers surrounded by much younger oceanic rock therefore posed a long-standing puzzle.

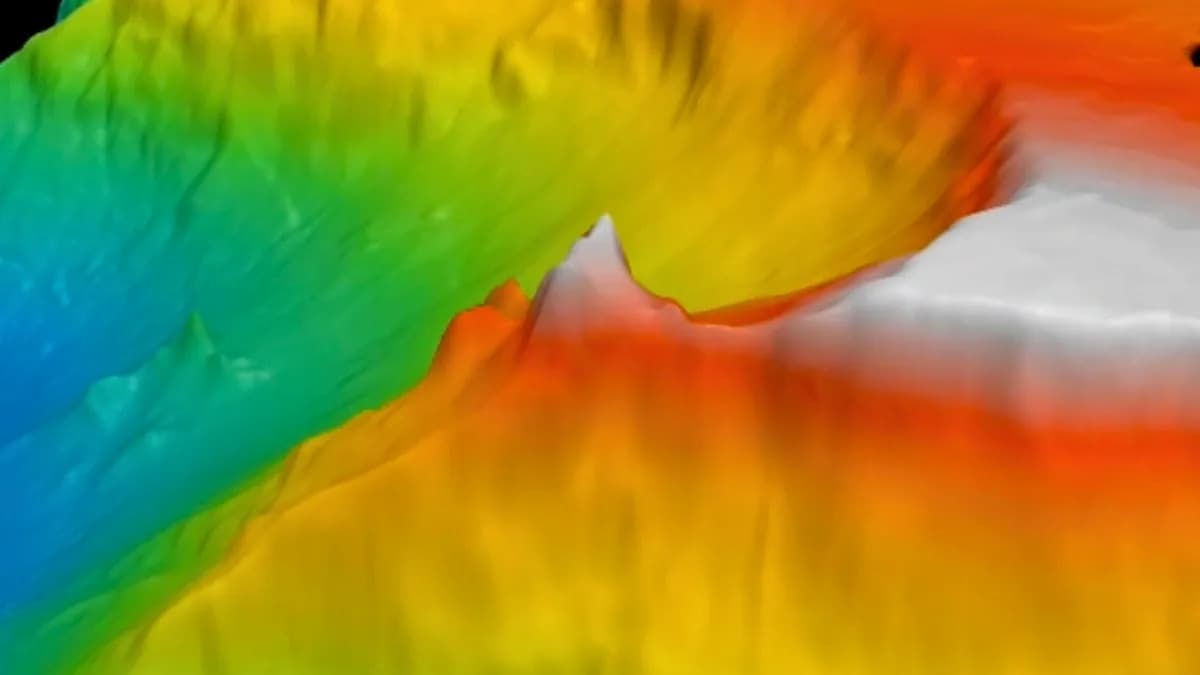

Researchers eventually noticed a pattern: these continental fragments are often located near transform faults, the offsets where mid-ocean ridges bend and adjacent crustal blocks slide past each other. To test how that pattern could form, Attila Balázs and colleagues at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zurich ran high-resolution, three-dimensional numerical models that reconstruct how continents tear apart.

What the Models Reveal

The models build on the memory of earlier plate collisions. When landmasses assembled into the supercontinent Pangea, the lithosphere fractured into many discrete blocks and weakened zones—like a plate that has been cracked or a glass that has shattered. Millions of years later, when those same regions began to rift, the inherited faults were reactivated and evolved into transform faults.

Under a specific set of circumstances, narrow ribbons of continental crust can be squeezed, uplifted and isolated along those reawakened faults. Key conditions are:

- Slow, oblique rifting so shear and twist concentrate stresses unevenly;

- Preexisting fractured or weakened lithosphere that focuses deformation;

- Some magmatic activity, but not enough to completely re-melt the isolated continental slivers.

When these conditions are met, small blocks of continental crust can be sliced off and carried onto newly formed oceanic seafloor along transform faults. According to Balázs, this sequence can take on the order of tens of millions of years—up to about 30 million years—to unfold.

Why This Matters

The study reconciles the existence of these oceanic continental fragments with plate-tectonic theory by showing that breakup is not always tidy. As Susanne Buiter of the GFZ Helmholtz Centre for Geosciences (not involved in the work) notes, three-dimensional models make it clear that continental separation can be messy, leaving behind isolated remnants that ride the new ocean basins.

Takeaway: Continental fragments in the middle of oceans are not anomalies outside plate tectonics but expected outcomes of complex, slow, and oblique breakup events that reactivate old faults and create transform-driven transport of crustal blocks.

Help us improve.