Researchers mapped deep-slope landslides off Crescent City, CA, and used radiocarbon dating of sediment cores to identify at least 10 earthquake-linked turbidites spanning ~7,500 years. The study—published in Science Advances and led by USGS geologist Jenna Hill with MBARI collaborators—finds continental-slope deposits are less influenced by coastal events and may provide a more reliable long-term record of Cascadia megathrust earthquakes. Signs of seafloor shaking tied to these deposits could also affect tsunami risk assessments.

Deep-Sea Landslides Reveal 7,500-Year Record of Cascadia 'Megaquakes'

Deep-sea landslides on the continental slope off Crescent City, California, preserve a seismic record that stretches back roughly 7,500 years, according to a new study in Science Advances. U.S. Geological Survey research geologist Jenna Hill and collaborators at the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute (MBARI) used detailed seafloor mapping, remotely operated vehicles and radiocarbon-dated sediment cores to link undersea landslides and turbidite deposits to ancient Cascadia megathrust earthquakes.

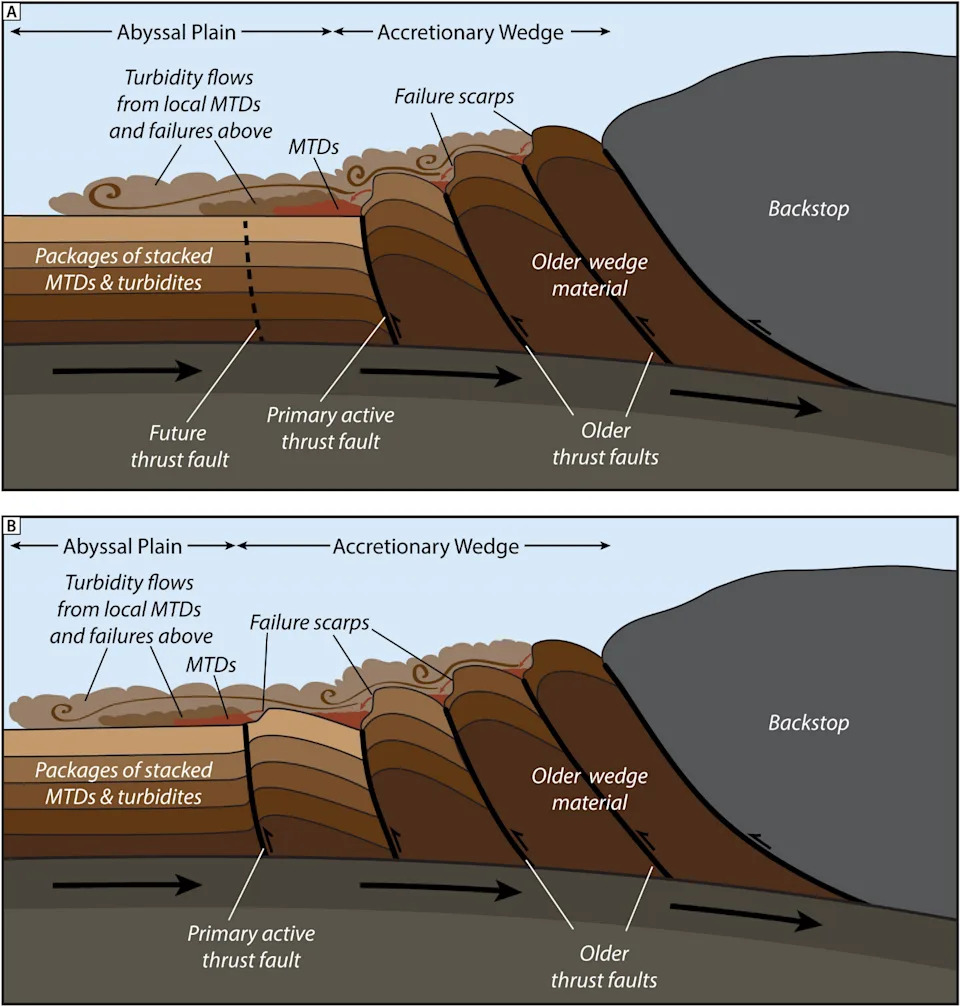

What the team did: The researchers mapped landslide scars and sediment layers on the steep continental slope — the transition between the continental shelf and the deep-sea plain — where deposits are less affected by coastal processes such as storms, tides and heavy rainfall. They recovered sediment cores and used radiocarbon dating to time-stamp turbidites (underwater sediment flows) and compare those ages with the timing of known prehistoric Cascadia earthquakes.

Key findings: The investigators identified evidence for at least 10 distinct earthquake-linked events over the past 7,500 years. These deep-slope turbidites correlate with landslides that the team interprets as being triggered by strong ground shaking. The researchers also observed indications of seafloor shaking associated with those events — an observation that may have implications for tsunami hazard assessment.

Why continental-slope turbidites matter: Turbidites found in nearshore submarine canyons can be produced by storms, currents or local slope failures unrelated to earthquakes, which complicates their use as seismic archives. By focusing on deeper slope deposits, Hill and colleagues argue they can more reliably distinguish earthquake-triggered turbidites and build a longer, cleaner record of large Cascadia earthquakes.

Broader significance: Subduction zones — where an oceanic plate dives beneath a continental plate — produce some of Earth's largest earthquakes, such as the 2011 Mw 9.1 Tohoku event in Japan. The Cascadia subduction zone, which runs from northern California to Vancouver Island, is capable of magnitude-9 or larger earthquakes. The team suggests similar deep-slope landslide records may exist at other subduction margins worldwide and could help extend quake histories where land-based evidence is sparse.

“We are able to clarify how and where the turbidites are generated,” Hill said. “So we know they're coming from landslides that we know are triggered by earthquakes.”

Remaining uncertainties: The study does not yet specify the minimum earthquake magnitude required to trigger deep-slope turbidites, but investigators note the shaking likely must be strong enough to cause substantial slope failure. Future work across other subduction systems will test how widespread and consistent these submarine records are.

Help us improve.