New research in Geology shows that several plankton species reappeared far sooner than expected after the Chicxulub asteroid 66 million years ago. Using helium-3 as a sediment clock across six sites, scientists estimate Parvularugoglobigerina eugubina appeared on average ~6,400 years after impact, with some sites indicating under 2,000 years. Between about 10 and 20 plankton species likely arose within ~11,000 years, highlighting a faster-than-expected ecological recovery, though species counts remain debated.

Life Bounced Back 'Ridiculously Fast' After Dinosaur-Killing Asteroid, Study Finds

New research suggests that some species returned far sooner after the Chicxulub asteroid struck 66 million years ago than previously thought. A study published Jan. 21 in the journal Geology reports evidence that several plankton species may have appeared within a few thousand years of the impact — a much faster recovery than earlier timelines indicated.

The asteroid, roughly 7.5 miles (12 kilometers) wide, struck near the Yucatán Peninsula and threw dust and soot into the atmosphere, producing a decade or so of cold, dark conditions. That environmental disruption contributed to the extinction of about 75% of plant and animal species, including all nonavian dinosaurs.

How the Team Recalibrated the Clock

Previous estimates for the first post-impact species were often based on assuming a steady rate of marine sediment accumulation, giving timelines on the order of tens of thousands of years. The new study uses a different chronological tool: helium-3, an isotope that arrives on Earth attached to interplanetary dust at a nearly constant rate. By measuring helium-3 concentrations through sediment layers, researchers can estimate how long those layers took to accumulate and thus better constrain the timing of fossil appearances.

Key Findings

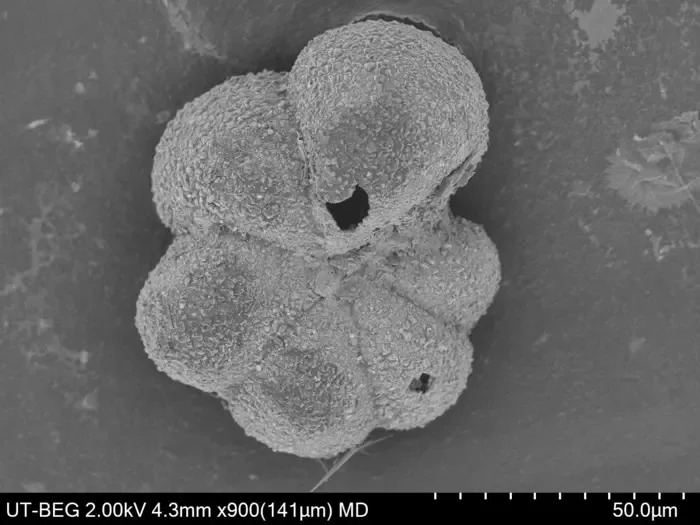

Reanalyzing previously collected helium-3 data from six marine sites, the authors found that the plankton Parvularugoglobigerina eugubina appeared, on average, about 6,400 years after the impact. At some sites the recalibrated first appearances are even earlier — under 2,000 years after the collision. Overall, between roughly 10 and 20 plankton species seem to have emerged within about 11,000 years of the event, although paleontologists continue to debate which fossil forms should be considered distinct species.

"It's ridiculously fast," said study co-author Chris Lowery, a paleoceanographer at the University of Texas Institute for Geophysics. "This research helps us understand just how quickly new species can evolve after extreme events and also how quickly the environment began to recover after the Chicxulub impact."

"The speed of the recovery demonstrates just how resilient life is," added study co-author Timothy Bralower, a geoscientist at Penn State. "To have complex life reestablished within a geologic heartbeat is truly astounding."

Implications and Caveats

Although many new species typically take millions of years to evolve, periods of ecological collapse and turnover can accelerate diversification. These results imply that complex ecosystems can rebound surprisingly quickly after catastrophic events, offering perspective on how modern ecosystems might respond to severe human-driven change.

However, the authors emphasize uncertainties: species counts depend on taxonomic interpretations of fossil forms, and local environmental conditions varied between sites. The helium-3 approach reduces some dating uncertainties but cannot fully resolve all questions about how quickly different lineages diversified.

Bottom line: Using helium-3 as a sediment clock, the study argues that the marine recovery after the Chicxulub impact was much faster than previously estimated, with some plankton species appearing within a few thousand years.

Help us improve.