The Sun recently produced multiple intense flares from a rapidly growing sunspot, including an X‑class event that caused radio blackouts in the South Pacific. November’s eruptions and associated CMEs triggered a powerful geomagnetic storm with auroras visible as far south as Florida. The article contrasts these events with the 1859 Carrington storm — which disrupted telegraphs and lit skies worldwide — and warns that a similar modern event could cause widespread, prolonged outages. Today, satellites like DSCOVR provide early warnings to help mitigate impacts.

How a Geomagnetic Storm Set Off Continent‑Wide Alarm — From Recent X‑Class Flares to the 1859 Carrington Event

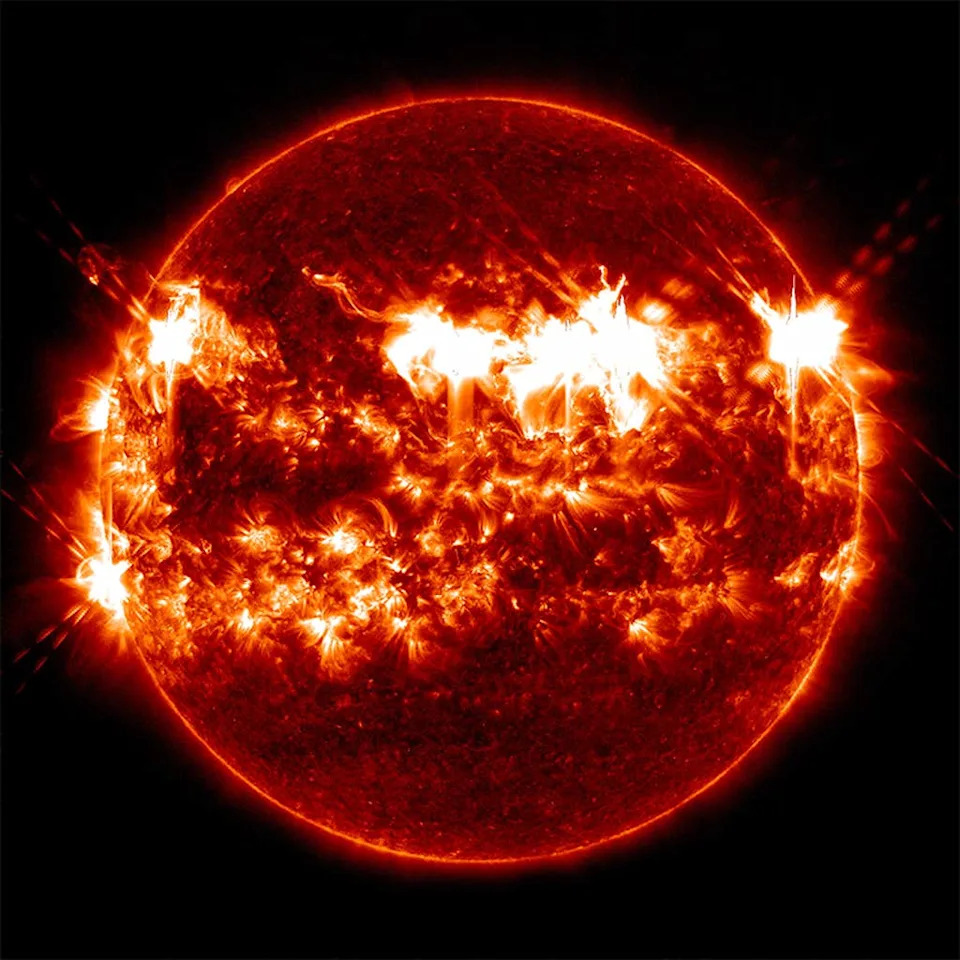

Our Sun recently unleashed a burst of intense activity from a rapidly expanding sunspot that spaceweather.com dubbed a “solar flare factory.” Among the eruptions was an X‑class flare — the most powerful category — which caused radio blackouts across parts of the South Pacific.

In November the Sun produced multiple X‑class flares and coronal mass ejections (CMEs) — clouds of plasma threaded with magnetic fields — that combined to trigger a dramatic geomagnetic storm. The storm painted vivid auroras across high latitudes and, in some places, produced displays visible as far south as Florida.

Solar activity follows an approximate 11‑year cycle that peaks in a period of heightened magnetic activity. The recent flurry of eruptions coincided with the Sun’s projected peak around 2024, when sunspots (regions of intense magnetic flux) and CMEs become more common. Those eruptions can disrupt satellite electronics, GPS navigation, HF radio communications, and electrical power systems on Earth.

Why the 1859 Carrington Storm Still Matters

The November storm was impressive but modest compared with the historic Carrington event of Sept. 1–2, 1859. Amateur astronomer Richard Carrington observed intense white patches on the solar disk that are now recognized as a powerful flare. That evening, auroras were so brilliant that they lit skies across North America and as far south as Cuba and Chile; miners in the Rockies reportedly rose at 1 a.m., thinking dawn had arrived.

The Carrington storm disrupted telegraph networks worldwide: operators reported sparks and shocks from equipment, and in some cases auroral currents were used to transmit messages without batteries. Contemporary descriptions stressed both the beauty and the alarm caused by the blood‑red auroras, and some witnesses feared fire or the end of the world.

Scientists estimate a Carrington‑class geomagnetic storm is a rare event — roughly once every 500 years — but if one occurred today it could cause prolonged, wide‑area electrical outages and serious disruption to satellites and communications.

Modern Monitoring and Preparedness

Unlike observers in 1859, we now have advanced space‑based monitoring. Spacecraft such as the Deep Space Climate Observatory (DSCOVR), operated by NASA and NOAA, and other heliophysics satellites continuously monitor the solar wind and incoming CMEs. Those observations give utilities, satellite operators, and emergency managers lead time to take protective actions.

While the odds of an extreme Carrington‑class storm are low, the potential consequences are large enough that continued monitoring, grid hardening, and preparedness planning remain priorities for governments and infrastructure operators.

Key takeaways: intense recent solar flares produced regional radio blackouts and spectacular auroras; the Sun’s 11‑year cycle brought heightened activity near its 2024 peak; the 1859 Carrington event remains the benchmark for extreme space weather; and modern satellites provide early warning that can reduce impacts on critical systems.

Help us improve.