The discovery of a mass grave at the hippodrome in Jerash, Jordan, provides direct archaeological and genetic evidence linking more than 200 burials to the Plague of Justinian. DNA from teeth confirms a single mortuary event associated with Yersinia pestis, and osteological data show a demographically diverse, largely transient population. The multidisciplinary study, published in February's Journal of Archaeological Science, connects biological proof to social context and draws parallels with modern pandemic dynamics such as travel immobilization.

Mass Grave at Jerash Confirms Human Toll of the Plague of Justinian

A US-led team of archaeologists, historians and geneticists has authenticated the first Mediterranean mass burial tied to the Plague of Justinian, providing new, human-scale evidence of how the pandemic affected urban life and mobility across the Byzantine world.

New Evidence From an Ancient Hippodrome

Published in the February issue of the Journal of Archaeological Science, the study analyzes DNA recovered from teeth and contextual archaeological data from a mass grave at the hippodrome in Jerash, Jordan. The genetic results indicate the burial represents “a single mortuary event” rather than the gradual accumulation typical of ordinary cemeteries. The team previously identified Yersinia pestis as the pathogen responsible for the outbreak.

Who Was Buried?

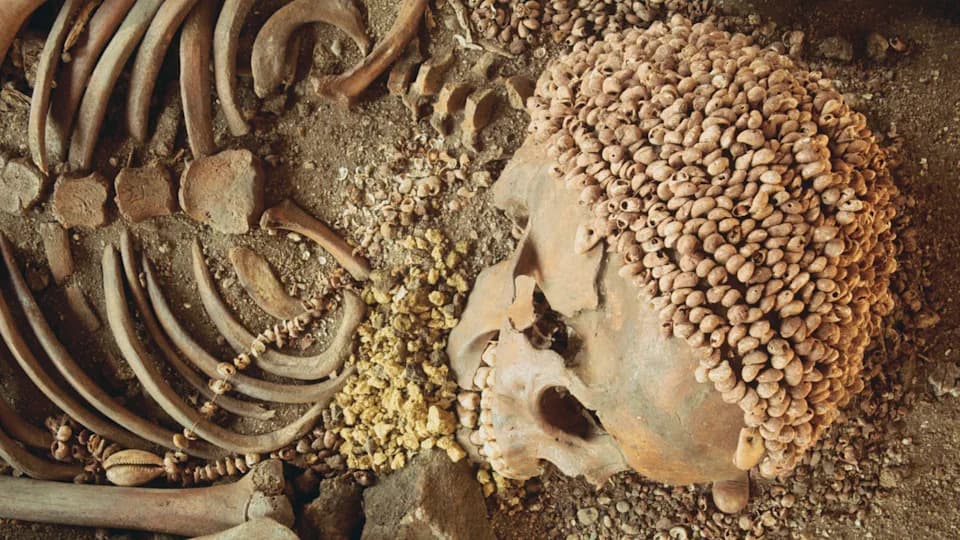

Excavations uncovered more than 200 individuals interred together. Osteological and genetic evidence show a demographically diverse group — men and women, older adults and teenagers — consistent with a largely transient population that included residents, travelers, mercenaries and enslaved people. Researchers conclude the group had been brought together and immobilized by disease, a dynamic the authors compare to modern pandemic travel shutdowns.

Methods and Multidisciplinary Approach

The research combined ancient DNA analysis, archaeological context, and osteological study. DNA extracted from dental samples provided the microbial signal linking these burials to Yersinia pestis, while burial patterns and artifacts helped reconstruct the social and environmental context of the deaths.

“Earlier work identified the pathogen. The Jerash assemblage translates that genetic signal into a human story about who died and how a city experienced crisis,” said Rays Jiang, the study's lead author and associate professor at the University of South Florida.

Implications

The Jerash mass grave offers a rare empirical window into the first recorded pandemic (circa AD 541–750). The authors argue the findings show how pandemics are as much social events as biological ones: disease disrupted mobility, concentrated diverse people in urban hubs shaped by travel, and exposed vulnerabilities not always visible in textual or economic records.

As the authors note, the evidence from Jerash counters arguments that downplay the pandemic's reality or scale: here is concrete microbial and mortuary data showing the plague reached Mediterranean urban centers. At the same time, the study cautions that widespread disease need not produce immediate social or political collapse — a distinction between biological impact and institutional change.

Conclusions

By linking hard biological data to archaeological context, the Jerash study transforms a genetic signal into a vivid account of human experience during the Plague of Justinian. The paper — authored by researchers from the University of South Florida, Florida Atlantic University and the University of Sydney — strengthens our understanding of how pandemics shaped ancient cities and offers useful comparisons to modern outbreaks.

Help us improve.