A single 10-hour dip in Kepler’s 2017 data suggests a possible Earth-sized planet, HD 137010 b, orbiting a star about 146 light-years away in Libra. Kepler captured only one transit during its shorter K2 campaign before the telescope was retired, leaving the candidate unconfirmed. Estimated orbital periods range widely (approximately 300–550 days), making follow-up timing uncertain. No current missions plan the long-duration monitoring needed, though future imaging-capable observatories could investigate.

Earth 2.0? A Lone Kepler Transit Hints at an Earth-Sized World — But Confirmation May Never Come

Astronomers say they may have spotted a rare candidate: an Earth-sized planet orbiting a sunlike star. The only evidence is a single, 10-hour dip recorded by NASA's now-retired Kepler space telescope in 2017. That solitary signal — seen in the star HD 137010, about 146 light-years away in the constellation Libra — looks promising but remains unconfirmed.

What Kepler Recorded

Volunteers sifting through Kepler's archival data via the crowdsourced Planet Hunters project flagged the brief dip in brightness. The pattern matched what astronomers expect from a small, rocky planet transiting its host star, and a team reported the possible detection in the Astrophysical Journal Letters. If real, the object would be designated HD 137010 b.

Why Confirmation Is Difficult

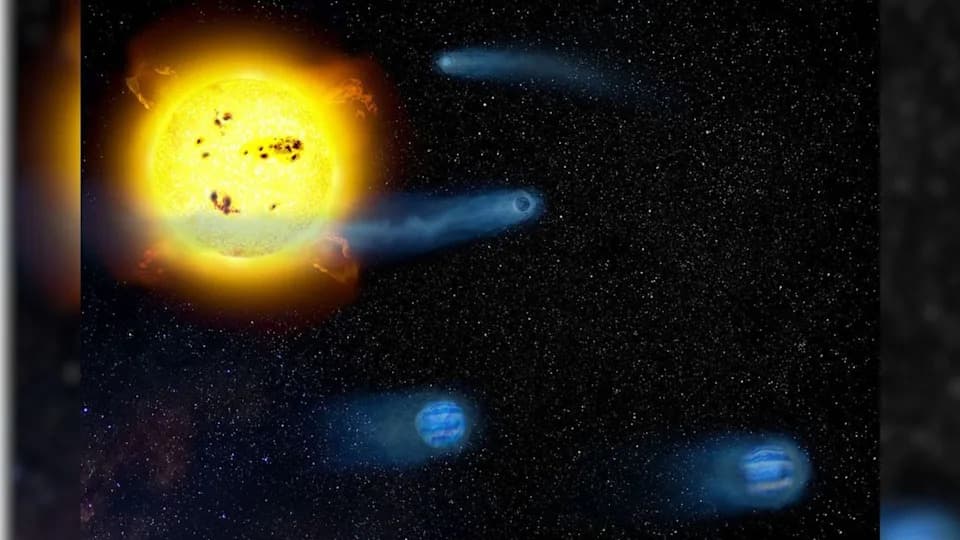

Kepler's primary mission relied on long, continuous monitoring of the same star field so repeated transits could be observed. After Kepler's stabilizing gyroscopes failed, the telescope entered the shorter K2 phase, in which each campaign lasted roughly 80 days. That limited cadence allowed only one transit of HD 137010 to be captured before Kepler ran out of fuel and was retired.

“The authors have tried to rule out everything they can from the data, but with only one transit, you can only do so much,” says Jessie Christiansen, an astrophysicist at Caltech. Vanderburg, a co-author of the study, adds that “it’s a very strong signal — it looks like a planet.”

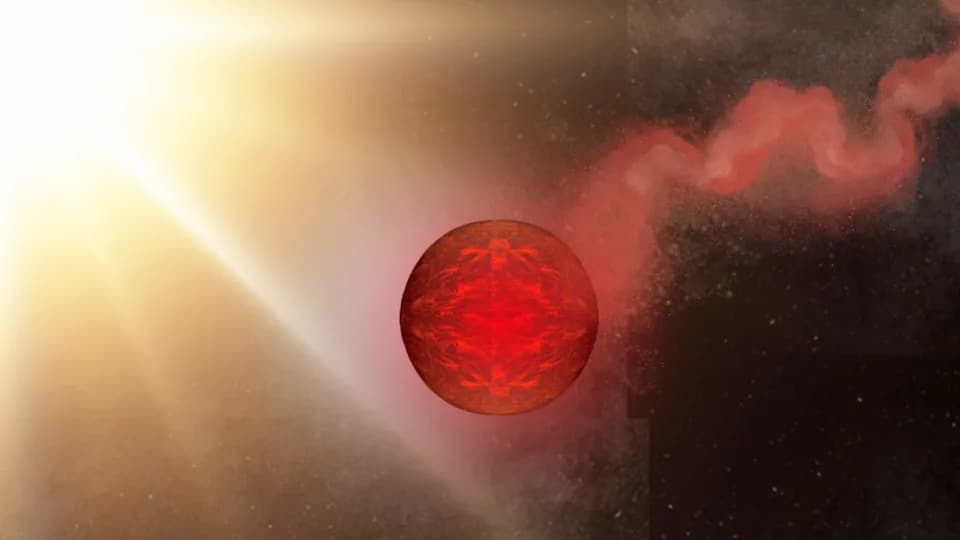

From that single event the team estimated the candidate's orbital velocity well enough to constrain a broad range of possible orbital periods: roughly 300 to 550 days. That uncertainty makes predicting the next transit difficult and leaves open very different scenarios for the world’s climate — it could be temperate and Earth-like, or distant enough to be a frozen, oversized analogue of Mars.

What Comes Next — And Why It’s Unclear

Confirming a small exoplanet normally requires at least two transits (a maybe) and preferably three transits to be confident. No current exoplanet-hunting observatory has scheduled the extended, repeated observations needed to catch additional transits of HD 137010 b. Because the star is relatively bright and nearby, it could become a compelling target for future instruments capable of directly imaging small exoplanets — but assigning time on multibillion-dollar telescopes to chase one unconfirmed candidate is a tough sell.

The authors and other researchers emphasize caution: some systems once believed secure after multiple transits have later proved to be false positives. Still, the clarity and strength of this lone signal make many in the community take it seriously. Vanderburg reflects that, had Kepler monitored HD 137010 continuously during its original four-year mission, multiple transits might have produced an undisputed “Earth 2.0.”

Bottom Line

HD 137010 b is an intriguing candidate for an Earth-sized planet, but with only one recorded transit and large uncertainty in its orbital period, its existence and habitability remain open questions. Future missions with long-term monitoring or direct-imaging capability will be the likeliest way to settle whether this is a true Earth analogue or a data artifact.

Help us improve.